Happy New Year! This week I had planned to publish an overview of the developments in transport in Paris in 2020, but I soon found that the year’s dramatic events warranted more than one article. Today, we start by looking specifically at long-distance transport of both people and goods.

The ongoing pandemic loomed large over the sector throughout the year, with travel patterns heavily impacted. But it affected different modes differently. Let’s look at them one by one.

Air

Since March, air traffic from Paris’s airports has dropped off a cliff. Passenger numbers during the first lockdown were next to zero, dropping 99% year-on-year in April and 98% in May. But even at the height of Covid-era air travel, during the relatively relaxed month of August, the difference with 2019 was a precipitous 69%. Indeed, although people did holiday in the summer, many chose to stay in France rather than travel abroad and risk falling prey to another nation’s rules in the case of worsening coronavirus statistics.

With flights grounded, some businesses have been forced to reduce their workforce. ADP, the Paris-based airport operator of CDG, Orly, and two dozen other airports around the world, is dropping 11% of its personnel. Air France is laying off thousands of workers. But for every airline job lost, many more could be lost among the company’s subcontractors and suppliers, such as cleaners and flight meal providers. Not to mention other companies supported by the industry: two hotels near Charles-de-Gaulle airport have closed.

Government support

As early as April, the government announced €7 billion in state-backed loans for Air France. In September, as part of a huge stimulus package, the aeronautical industry was allocated €1.8 billion, but this is specifically targeted towards manufacturing. The government is looking to fund research and development, with a view to seeing hydrogen-powered or electric planes in the sky by the mid-2030s.

Cargo

The silver lining for airlines is the need to transport medical supplies. The French authorities have been heavily criticised for their policy relating to masks during the first wave of the virus. The country was faced with a huge shortage in March, leaving medical workers caught short. Rather belatedly, France ordered 1 billion masks from China, delivered by plane to Charles-de-Gaulle and Vatry airports.

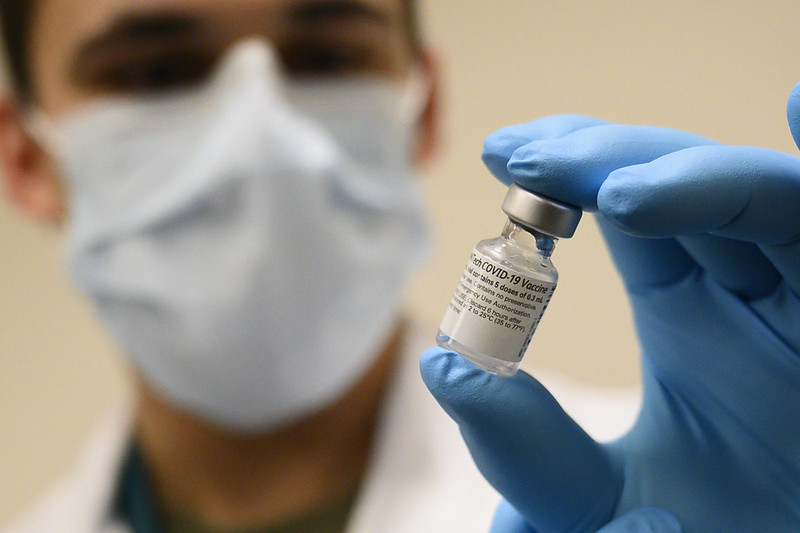

Now, the subject of the moment is vaccines. All of the different vaccines must be kept cold; the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, first to be approved in the EU, must be stored at -70 °C. Transportation must also be secure – Jürgen Stock, secretary general of Interpol, has described the vaccines as “liquid gold”, with tales of vaccines being sold on the dark web – and is of course time-sensitive. All of these factors mean that air transport is set to be vital in moving them around the world. As Europe’s second busiest cargo airport, Charles-de-Gaulle will play an important role here. Notably, French flag carrier Air France, equipped with 99 long-haul planes and 2 cargo aircraft, has been preparing for this challenge.

On the other hand, aeroplanes will only have 30% of modal share here: the sea is favoured for long-distance transport of parts such as syringes and packaging, while shorter distances are being covered by road. For example, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is arriving in France from factories in Belgium by lorry.

Rail

The SNCF, already impacted by the most widespread strikes for a generation starting in December 2019 and continuing into January, suffered a collapse in revenue once the country locked down. The national railway operator cut much of its service, in particular the TGV and Ouigo high-speed trains. During the first national lockdown, from 17 March to 11 May, 93% of high-speed services and 82% of TER (regional) trains were suspended.

Passenger numbers bounced back during the summer, when many French residents holidayed domestically: by offering more low-cost journeys than normal, the SNCF managed to reach 85% of its typical summer ridership. But in the autumn, weekday journeys saw 60-70% fewer passengers than usual, with business travel depressed. The SNCF pushed the pause button on 5% of TGVs during this time.

The second national lockdown, from 30 October to 15 December, was less severe than the first, with many businesses which had closed in March remaining open. This time, 70% of regional TER services were maintained, but once again high-speed journeys were drastically cut, by around 70% overall and up to 80% on some routes.

After the end of the second lockdown, many restrictions remained in place, but travel between regions was opened up, and millions of people rode the SNCF’s trains to spend time with their families over Christmas. However, ridership was down 30% from a typical festive season, from 5 million to 3.7 million. This compounded the company’s annual losses, estimated at the beginning of December to amount to some €5 billion.

Stimulus

Though our focus has necessarily been diverted from the ongoing climate crisis to the more immediate health emergency, the former has not gone away. As such, it’s crucial that governments support the rail industry, which is a vital alternative to more polluting cars, lorries and aeroplanes. In September, the French government pledged €4.7 billion to the sector, including €3.8 billion for SNCF Réseau, which manages the nation’s railway infrastructure. But to meet its annual shortfall, the SNCF has had to turn to other sources, including the sale of subsidiary Ermewa, which leases goods wagons and tank containers, for an estimated €2.5 billion.

Sleeper trains

The SNCF once boasted an extensive network of night trains, but in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, most of these were cancelled, falling victim to competition from the expanding TGV network and low-cost flights. Two cancelled routes will now be reopened, linking Paris with Nice and the Spanish border at Hendaye, while the company’s two remaining routes are being modernised.

As well as these domestic services, a partnership between Austrian federal rail operator ÖBB and the national railways of Germany, Switzerland and France is rolling out night trains across Europe, including two with Paris as a terminus: to Berlin from December 2023 and to Vienna as early as December 2021.

Freight

Rail freight in France is set to receive a boost, with two new rolling highways1 linking the English Channel with the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. And the “greengrocers’ train” from Perpignan to Paris’s international food market at Rungis, cancelled in summer 2019, is set for revival, perhaps as early as summer 2021. The service could even be extended south to Barcelona and north to Antwerp.

In 2018, rail represented only 9.9% of inland goods transport in France, while road transport accounted for 87.8%. The modal share for rail in France is half that of Germany and a third that of Austria or Switzerland. The government’s investment plan only allocates €200 million to freight rail; the sum necessary to double rail’s modal share by 2030 has been estimated at €15 billion. France’s highly electrified network, together with its low-carbon electricity production2, means that rail produces 9 times less carbon dioxide and 8 times less particulates than using lorries. Investing in this transition should be a priority as France recovers from the coronavirus crisis.

Road

Coach

Private long-distance bus companies, a relatively new phenomenon in France thanks to deregulation in 20153, saw some of 2020’s biggest transport service cuts: Flixbus offered no journeys at all during the second lockdown, restarting on 17 December, while BlaBlaBus is still completely paused and not expected to open coach routes again before March 2021.

Car

As we’ve seen, rail journeys were down markedly from the previous year, and flights and coach travel were even more severely impacted. On the other hand, perhaps unsurprisingly given the dangers of sharing an enclosed space with strangers, the private car seems to have fared well.

The roads were almost completely empty during the first lockdown, and highways were much emptier than normal during the second, even if the streets of Paris were much busier with motor traffic than the first time around. But in some of the intervening period, traffic was close to normal, especially with the arrival of the summer holiday season.

August weekends are notorious for heavy traffic on the motorway system. In particular, the first weekend of August plays host to the “chassé-croisé”, where “juilletistes” (“Julyists”) returning from their holidays share the road with “aoûtiens” (“Augustians”) heading to theirs. With 760 km of traffic jams, nationwide, Saturday 1 August 2020 was almost identical to the equivalent Saturday the previous year (762 km).

On two notable occasions, congestion reached levels significantly above those of a Covid-free year: the start of each lockdown. On the eve of the first lockdown, roads throughout Île-de-France were clogged as Parisians fled their small apartments to be somewhere more spacious and, perhaps, less alone.

The region’s roads were even more congested the day before the second lockdown took effect, with traffic jams in Île-de-France reaching 736 km, close to the all-time record. But this time most of the traffic was from trips within the region rather than people leaving the city. With more workplaces, and in particular schools, remaining open, an escape to the country was less of an option. The reduced severity of the restrictions might also have played a part: for example, parks stayed open this time. Instead, locals were making trips to the shops, having a last few drinks at the bars or travelling to see friends and family.

Lorry

As we’ve already seen, the vast majority of goods in France are transported by road rather than rail or waterway. And this is one sector which continued to operate throughout both lockdowns despite difficult conditions. At the start of the first lockdown, drivers found themselves unable to buy food or use the toilet as motorway service stations closed. France has accelerated the naturalisation process for front-line workers who worked through the coronavirus crisis, producing an indicative list of recognised professions for this procedure. Lorry drivers figure on this list. Curiously, public transport workers are not explicitly mentioned.

On the other hand, the road transport sector was not allocated any of September’s stimulus package.

The story continues

Coronavirus case numbers in France are still high, and the English and South African variants are causing concern. 2021 is shaping up to be another difficult year for the transport sector.

On the local level, the story isn’t exactly the same: although the Parisian transit network has seen reduced ridership, it’s also received considerable support from the government, alongside major developments that had been planned before the crisis hit. And urbanists across the world have had their eyes on Paris as the city invests in active travel and continues to reduce the dominance of the private car, bolstered by the reelection of mayor Anne Hidalgo in June. Next time, we’ll place the spotlight on the year’s most important news in local transportation.

-

These rolling highways, or autoroutes ferroviaires, will connect Calais in the north with Sète on the Mediterranean coast, and Cherbourg on the Norman coast with Bayonne near the extreme southwestern corner of France. France already boasts two such services, in which lorries piggyback on trains: one from Bettembourg in southern Luxembourg to Perpignan on the Mediterranean near the Spanish border, and another through the Fréjus rail tunnel across the Alps into Italy. ↩

-

As of 2019, more than 70% of France’s power came from nuclear, with more than 20% from renewable sources. ↩

-

the controversial loi Macron allowed companies other than the SNCF to operate long-distance domestic coaches, which came to be known as Macron coaches. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris