Happy New Year! Last week, we looked at the big changes in public transport in the Paris region in the last decade. In the first issue of 2020, let’s look ahead to what’s planned for the next ten years.

Metro

Besides the automation of line 1, developments on the Paris metro network in the 2010s were relatively small and piecemeal. Not so in the 2020s. By 2030, if all goes to plan, there will be four new lines, while one existing line will be automated and four extended.

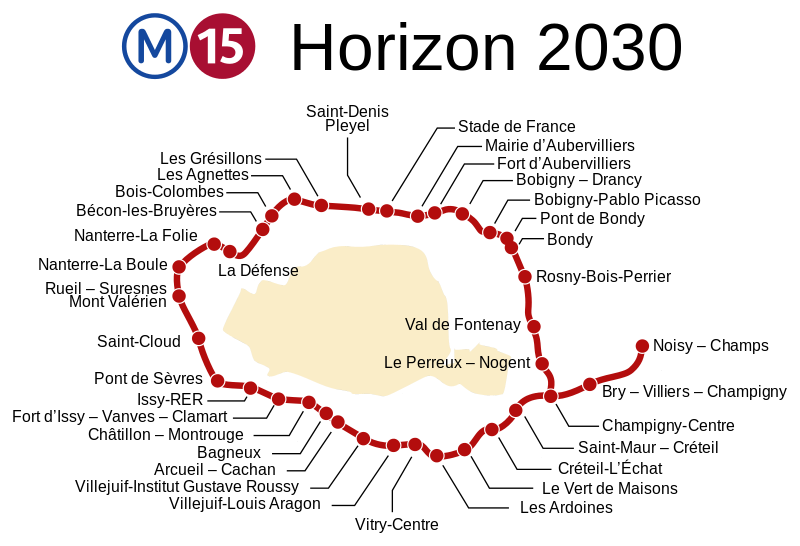

The new lines, numbered 15 to 18, will run exclusively outside Paris. Line 15 will eventually form a ring linking inner-ring suburbs, with line 16 running further east, line 17 from Saint-Denis to Charles de Gaulle airport, and line 18 from Versailles to Orly airport. Extensions to line 14, northward to Saint-Denis and southward to Orly via Villejuif, will connect these new lines to the existing Parisian network.

Together, these developments form the Grand Paris Express, a huge new transport project aiming to connect Paris’s periphery more closely with the central city. The largest urban project in Europe, this will double the total length of the metro, with 200 km of new lines. With house prices inside Paris higher than ever and still rapidly rising, recent population growth has been in the suburbs. The Grand Paris Express will help millions of residents of these suburbs to reach their jobs more easily. The 68 new stations will be accompanied by new, transit-oriented development of all kinds. The new transport should reduce road congestion and the carbon emissions and urban pollution associated with car travel.

In time, this project could have a more profound cultural impact. Today, the distinction between “Parisians” and “banlieusards” is very clear. When the metro was first developed at the end of the 19th century, it was deliberately confined to the city proper, as Parisians feared opening it to the suburbs would present a security problem. The decision to run trains on the right, as opposed to the left (as they do on the mainline) was a conscious effort to prevent integration between the metro and the suburban railway. While many metro lines do now reach into the nearest suburbs, there is still a stark contrast between coverage inside the city limits and outside the old walls.

Besides these dramatic developments, three other lines are due to be extended in the next few years:

- Line 11 is scheduled to add 6 new stations in the east by 2023, terminating in Rosny-Bois-Perrier, where it will connect with RER line E and, eventually, metro line 15.

- Line 4, extended south to Montrouge in 2013, should reach Bagneux by mid-2021.

- Line 12, extended north to Front-Populaire in Aubervilliers in 2012, should reach the centre of Aubervilliers by the end of 2021.

The other big metro development of the next decade is the automation of line 4. Work on this line has been underway since 2016; the first driverless trains are expected this year, with the project to be completed in 2022.

RER

Like the metro, the RER didn’t see a lot of development in the 2010s. But by 2024, line E is set to be doubled in length, extending west from its current terminus at Haussmann – Saint-Lazare, through Nanterre, to Mantes-la-Jolie near the western edge of Île-de-France.

The RER E was completed in the 1990s and included two spectacular underground stations. The western extension, planned in some form since the line’s inception, includes new subterranean stations at Porte Maillot and La Défense. Planning the new station at La Défense was no mean feat, as the underground environment there is already very dense, with existing transport infrastructure and the foundations of the business district’s many skyscrapers. The new station will be situated underneath the CNIT, a building housing shops, offices and a business school campus.

West of La Défense, another new station will be opened in Nanterre, beyond which trains will run on track currently used by the suburban railway (Transilien line J from Saint-Lazare). This could also relieve the RER A, one branch of which currently uses the same track, allowing its trains to better serve the branch to Cergy-Le-Haut.

Lines A and B are also set to see changes, with a number of stations renovated. Most notable on the list is Auber on line A, which welcomes 180 000 passengers a day in a vast underground hall. The renovation will make it brighter, greener and more accessible, as well as introducing new USB phone-charging points and interactive journey planning screens. Line B is also set to receive new, higher-capacity trains starting in 2025.

CDG Express

Currently, tourists hoping to reach the city from Paris’s largest airport have a choice of road transport or the RER. By the end of the decade, they’ll have another option: a direct, non-stop rail line. The CDG Express, linking Charles de Gaulle airport with the Gare de l’Est, will take only 20 minutes. But it’ll cost €24, more than double the current price of the RER journey. Originally hoped to be up and running in time for the 2024 Olympics, it’s now expected at the end of 2025. The new line has been criticised as favouring moneyed tourists at the expense of daily commuters: the new trains will run on tracks currently used by the RER B during disruption, an all-too-common occurrence.

Tramway

The trams of Île-de-France have seen dramatic development over the last ten years. This progress is set to continue in the next decade, with four new lines: two in the nearer suburbs, and two tram-trains further out. Three lines are set for extensions, including line T3b, due to reach Porte Dauphine at the end of 2023. It was once hoped that this would eventually link up with line T3a at Pont du Garigliano, creating a modern version of the Petite Ceinture, but this was opposed by the inhabitants of the less densely-populated 16th arrondissement.

Bus

The 2020s will see the culmination of a number of Bus Rapid Transit projects, under the banner of T Zen. Line 1 was inaugurated in 2011; it will be joined this decade by four more suburban lines, including two with termini inside Paris.

Existing lines are also set to continue their transition to electric buses, with 800 due to hit the streets by 2022, including an air-conditioned model with four-wheel steering.

Cars, cyclists and other road users

As I detailed last week, Paris’s streets have seen a lot of changes recently, reducing the place of the private car in favour of cyclists and pedestrians. The city plans to outlaw petrol and diesel cars by 2030, and incumbent mayor Anne Hidalgo wants to expand on recent work with more transformations, including a new park linking the Eiffel Tower with the Trocadéro. Another plan is to convert the boulevard périphérique from a controlled-access highway to a more typical urban boulevard, reducing the number of lanes and dropping the speed limit from 70 to 50 km/h.

Happily, her main rivals in this March’s municipal elections also acknowledge the need to encourage Parisians out of their cars. Benjamin Griveaux, the mayoral candidate from Macron’s LREM, agrees that the périphérique needs to change, and advocates a lane dedicated to carsharing and public transport. Independent Cédric Villani defends the périph in its current form, but advocates new pedestrian zones and an expansion of pro-cycling policy.

One of the things I love about living in a city like Paris is that wherever I go, I’m surrounded by history. Indeed, the goal of Fabric of Paris is to draw attention to the stories behind the places and things we interact with every day. But as we’ve seen, Paris’s story is far from over. It’s exciting to picture the region ten years from now, rich with another decade of history woven into its fabric.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris