Paris’s rich history includes an extensive list of infrastructure projects which once served an important transport role, but have since fallen out of use. Of those, some have been lost forever to demolition, but others have seen new life in other domains. This post is the first in a series looking at some of these new uses. Here, the subject is parks.

It might not have many towering high-rises, but Paris is a very crowded city. The city proper has a population density comparable with that of Manhattan. At the same time, it’s a very liveable city, with remarkably many green spaces. I’m often impressed to stumble upon a public “square” (to use the French word) squeezed improbably among buildings.

Paris is continually improving its park offering, and one way to do that in an already crowded city is by recovering land that was previously given over to transport. Here are a few examples.

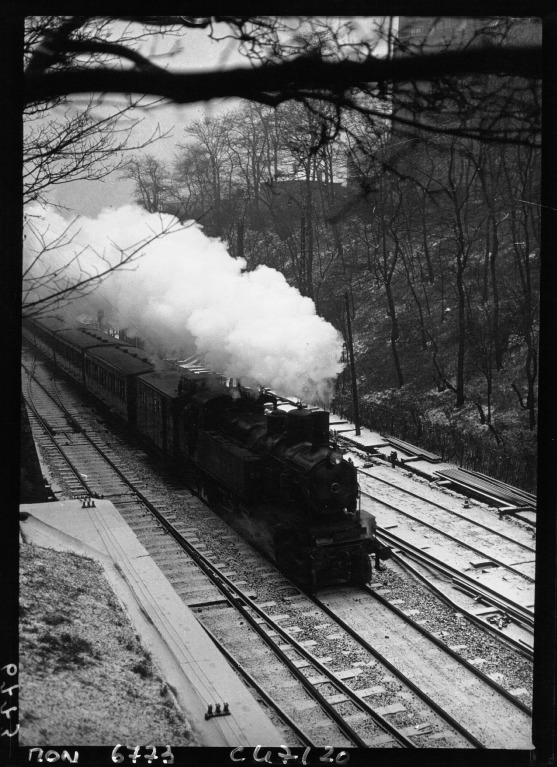

Promenade plantée

Probably the most well-known is the Promenade Plantée (officially the Coulée verte René-Dumont), a “linear park” occupying the former Ligne de Vincennes railway line, which ran from a (now demolished) terminus at Bastille to the eastern suburbs. The western portion runs along a viaduct offering great views (the inspiration for New York’s High Line), while to the east it runs in a cutting and through two tunnels. At intervals the route crosses other parks, notably the Jardin de la Gare de Reuilly (occupying the grounds of a disused station) and the Square Charles-Péguy (the site of the curve where this line joined the Petite Ceinture).

It’s not just inside Paris that the Ligne de Vincennes has found new life as a park. Further out, in the Seine-et-Marne department, the Chemin des Roses was inaugurated in 2010 along an 18 km stretch between the towns of Servon and Yèbles.

Coulée Verte du Sud Parisien

In a similar vein, the disused Ligne d’Ouest-Ceinture à Chartres is now the site of the 14 km Coulée Verte du Sud Parisien, officially the Promenade départementale des Vallons-de-la-Bièvre. This “greenway” provides an off-road route from the southern suburb of Massy to the edge of Paris. The railway line was only ever partially completed: work slowed and was eventually abandoned thanks to the First World War. But the reserved space remained, and became a line of green through an otherwise built-up area. The route was touted in the 1960s as an extension to the A10 motorway; in the end, the high speed rail line to western France was built here, opening in 1989. But this still left room for the Coulée Verte, which opened alongside the LGV in 1996.

Petite Ceinture

The Petite Ceinture was a railway running in a loop around the edge of Paris, providing a freight link between the terminal stations and a passenger route around the city. Very popular at the end of the 19th century, from the early 1900s it faced competition from the metro, and local passenger traffic on most of the line ceased operation in 19341. While parts continued to be used by freight traffic, others began to fall into disrepair. Various changes from then onwards created opportunities for parks. For example, in 1986, the site of a demolished goods station in the 20th arrondissement became the Jardin de la Gare de Charonne, named after the station it replaced. In 1989 the Jardin de la Dalle-d’Ivry was opened on a former section of the line in the 13th arrondissement.

Not all of the line was destined for permanent abandonment. Most of the Ligne d’Auteuil, the western portion of the Petite Ceinture, was taken over in 1988 by RER line C. At this time, this part of the line (which ran in a trench) was covered over to reduce noise pollution, creating space above for new parks in the 16th and 17th arrondissements: the Square Jan Doornik and the Promenade Pereire.

More recently, the disused parts of the line have been completely taken over by nature. Intrepid locals were already starting to take advantage of this, breaking in to enjoy the peace and greenery, but more recently the city authorities have been progressively opening sections up, starting in 2007 with the Petite Ceinture du 16e. The plan is for 8 km of “linear parks” to be open to the public by 2020. To celebrate this, the end of August 2019 saw the Fête de la Petite Ceinture .

Freight yards

It’s not only the lines and stations that can be transformed into parks. In the 17th arrondissement in northwestern Paris, a vast area of rail freight yards is becoming the Parc Clichy-Batignolles — Martin-Luther-King. This park has been open since 2007, but is still being expanded.

Either side of the railway into the Gare de l’Est stand two parks, the Jardins d’Eole and the Jardins Rosa-Luxemburg, occupying space formerly belonging to the SNCF. On the east, the Jardins d’Eole replace a freight station, while on the west, the Jardins Rosa-Luxemburg have invaded the grounds of a disused warehouse and goods shed. Part of the park is covered by the roof of the goods shed, which also features solar panels.

Canal Saint-Martin

The Canal Saint-Martin was completed in 1825, and served to bring fresh water to central Paris, as well as to provide a route for deliveries of grain and building materials. Crossing an increasingly populous area, the canal soon caused major traffic disruption on the surrounding roads, leading in the mid-19th century to the burial of a section under the Boulevard Jules-Ferry and the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir. The land thus created (between the carriageways) was then used for the Square Jules-Ferry and the Jardin May-Picqueray, created in the 1920s.

Bercy

From the early 19th century, the suburb of Bercy, just outside the city walls, was the site of a vast area of warehouses to store wine and liquor arriving in Paris by boat and, later, by rail. After 1860, when Paris annexed the area, it continued to thrive until the mid-20th century, when changing consumer habits, transport and storage left the area abandoned. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the area would begin to be transformed, with the arrival of the Bercy Arena and the Finance Ministry. In 1997, a large part of the area became the Parc de Bercy. Its history can still be seen in the preservation of some of the buildings, rails and roadways of the site, and is reflected in a newly-planted vineyard within the park.

Banks of the Seine

In the 1950s and 1960s, as Europe recovered from the Second World War and the private motorcar became affordable to more and more people, officials began to believe the best way to serve their citizens was to reorient their cities around cars. We now know how misguided they were: the basic geometry of a dense city and the phenomenon of induced demand, not to mention the dual scourges of urban pollution and human-induced climate change, mean that designing for walking, cycling and public transport is a far better bet. But back then Europeans were following in the footsteps of American city planners in dreaming up extensive motorway networks right in the centre of cities. London’s Ringways were one such vision; Paris had the Plan autoroutier pour Paris.

Mercifully, only a small part of these plans ever came into fruition: many locals were opposed from the start, and the 1973 oil crisis and 1974 death of President Georges Pompidou put an end to them. However, the Voie Express Rive Gauche and the Voie Georges-Pompidou, one-way multilane highways on each bank of the Seine, were completed and served for several decades as city-centre expressways.

As early as 1995, this began to change as these roads were closed to traffic on Sundays. Then in 2002 came the Paris Plages, a “beach” on the banks of the Seine that involved closing the roads for a month in the summer. The success of this initiative likely contributed to the 2013 decision to close the Voie Express Rive Gauche to traffic permanently, and the 2016 decision to close the central section of the Voie Georges-Pompidou. Despite fierce opposition by many on the right and from the suburbs, these have proved popular with Parisians and tourists alike, and constitute one of Paris’s most recent examples of transport infrastructure being converted to a park. Children’s play equipment, cycle hire stations and seating complete the offering.

The future

In recent years, public policy in Paris has placed great importance on creating useful, high quality green spaces. A lot of the parks on this list are newer than the current millennium, and this list will likely be out of date by the time you read this as the city continues transforming spaces (not least with the ambitious project for the Petite Ceinture).

Perhaps the most high-profile priority for mayor Anne Hidalgo has been breaking the supremacy of the private car, to improve both the local air quality and the city’s carbon footprint. In the same manner as the banks of the Seine, I think we can expect more parks to encroach on spaces previously reserved for the car. As this article concludes, “And tomorrow? What if it were roads and car parks that we turned into parks?”

-

An earlier version of this article stated that the Petite Ceinture had closed to passenger traffic in 1934, which is not quite true, as reader Mike Mellor pointed out. Long-distance night trains continued to use the line for journeys between the north and south east of France. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris