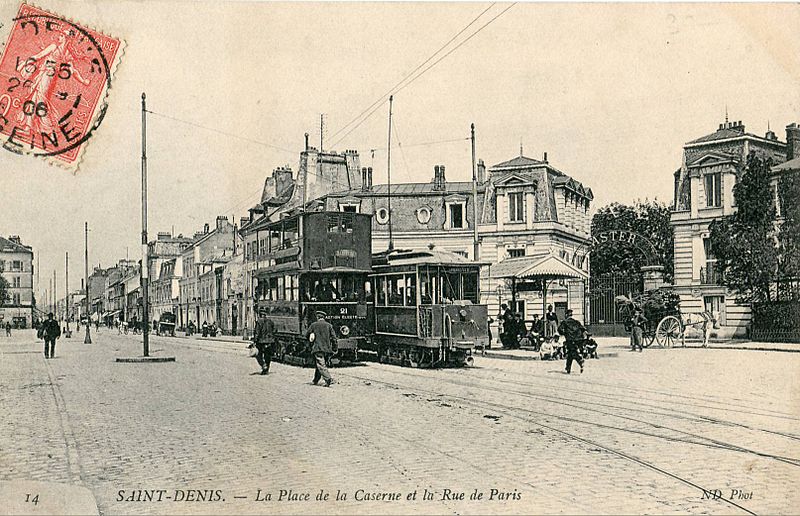

The Île-de-France tramway was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The first lines were replaced by buses in the mid-1920s. By the end of the 1930s, trams had disappeared altogether from Paris. A few lines in Versailles subsisted, but in 1957 even they were abandoned. The old tramway was as dead as a doornail.

And yet, at the time of writing, there are 12 lines totalling 156 km. Two new lines are set to open this year, and several extensions are in the works. So it’s fair to say that in 2023, the tramway of Île-de-France is very much alive. What changed?

The end of an era

In part 7, we saw how the rise of the motorcar spelled the end for the region’s trams. Paris, though earlier than many, was far from unique among French cities in closing down its tramway network. For the next several decades, the car was at the centre of mobility policy across the country and around the world. In many ways, this is still the case: just look at the pushback whenever a city removes some parking. But for the last few decades, the tide has been turning. And the start of that slow turn can be traced to the early 1970s.

In October 1973, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia declared an oil embargo that sent oil prices into a steep climb. We’ve seen before on this blog the role this crisis had in the end of Aérotrain and the demise of the Paris motorway plan. For the first time since the Second World War, western countries began to seriously question their reliance on oil.

A few months later came another event, closer to home. On 2 April 1974, Georges Pompidou became the only president of the Fifth Republic to die in office, succumbing at the age of 62 to a rare cancer. Pompidou had famously said Paris should be “adapted” to the car. His prime minister in the early 1970s was Jacques Chaban-Delmas, who as mayor of Bordeaux had decided to abandon trams there, and harboured plans to axe even the remaining bus network in favour of the private car.

Pompidou’s successor was Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, a moderniser known for investing in nuclear power and the TGV as well as for social policies like divorce reform and legalising abortion. He also proved willing to move on from the postwar tout-voiture orthodoxy, appointing an engineer named Marcel Cavaillé as transport secretary. Cavaillé’s four years in this office would be remembered for two things. One is the Carte orange, a unified multimodal transport pass for the Île-de-France region introduced in 1975. The other is the Cavaillé contest: an initiative to bring back trams to mid-size cities in France.

The contest

Cavaillé kicked off the process with a letter to eight cities around France, from Nancy to Toulouse. In his letter, the minister asked them to consider introducing tramways. Or rather, reintroducing: all eight cities had had tramway networks before, but they had all been removed in the 1950s, at the height of the car cult.

Cavaillé wanted to avoid costly infrastructure projects in these mid-size cities where buses weren’t enough, but an underground metro would be overkill. He also rejected futuristic alternatives – which were all the rage in this period – arguing that tramways were the only mode perfectly suited to this niche.

In August 1975, Cavaillé launched a contest to design a modern tram. One of the keys to making a new generation of tramways a success was performant, high-capacity rolling stock. Two entries were selected the following year, including one from a group led by French multinational Alstom (then Alsthom). But their designs went unrealised.

The trouble was that trams had an image problem. They were remembered as a throwback: an old-fashioned obstacle to traffic, requiring annoying rails and unsightly overhead wires. The government’s attempts to rebrand them “light metros” did little to temper this feeling. Remember how recently the last trams had been removed: the decisions Cavaillé was calling into question were no older in 1975 than Taylor Swift’s career is today. As Chaban-Delmas, still mayor of Bordeaux, put it, “I didn’t remove the tramway to put it back now”. The response from the other seven cities was similar.

Provincial pioneers

All was not lost.

Nantes

A few years after Cavaillé’s proposal, one city – not on the original list, but similar in profile – stepped up. Nantes, a city of some half a million people in northwestern France, had a track record of transport innovation: as we saw in part 1, it’s where the bus was invented. And it would become the first of dozens of French urban areas with a modern tram network.

Nantes had lost its last tramway in 1958. But in a show of great political courage, Alain Chénard, elected mayor in 1977, embarked on a project to open a new line. It was controversial: the municipal opposition attacked him for the disruption caused by the construction work. His mandate wasn’t renewed in 1983. Line 1 opened in January 1985, but there was no formal inauguration: Chénard’s conservative successor opposed the project.

But the success of the tramway spoke for itself. By the end of 1985, the trams were already experiencing overcrowding at rush hour. In 1989, future socialist prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault took over at city hall and quickly got to work on a second line.

For its rolling stock, Nantes called on Alsthom, who were able to reuse their work for the Cavaillé contest. The result was the TFS: “tramway français standard”.

Grenoble

The first of Cavaillé’s candidates to jump on the modern tramway bandwagon was Grenoble. This Alpine city had been investigating options for a new transit system, including gadgetbahns like the Poma 2000 people mover. But in 1983, a pro-tram mayor was elected, and promptly called a referendum on a new tramway. Although trams weren’t yet circulating in Nantes to prove the concept, the people of Grenoble still said yes, with 53% of votes in favour. Some might call that an overwhelming majority…

It’s worth noting that attitudes to trams didn’t fall along traditional left-right lines. In Nantes the opposition came from the right, but in Grenoble it was the other way around.

Grenoble proved a pioneer in an important way. The first TFS was exclusively high-floored, requiring steps to board. That didn’t fly with local disability rights organisations, who campaigned tirelessly and successfully for Grenoble’s trams to be different. The version of the TFS which Alsthom ultimately proposed there had a low-floor section, allowing level boarding in the centre of the vehicle. Line A of the Grenoble tramway entered service in 1987.

Nantes would later retrofit its trams with a low-floor middle section.

Growing popularity

The success of the tramways of Nantes and Grenoble didn’t go unnoticed. Soon, dozens of French cities were building them, including all but one of those on Cavaillé’s original list. But the earliest adopters weren’t in the chosen eight. They included Strasbourg, Montpellier, Lyon, and – before any of them – the subject of this article: Paris.

In Bordeaux, Jacques Chaban-Delmas declined to stand as mayor for a tenth term in 1995, leaving city hall at the age of 80 after 47 years in office. His chosen successor Alain Juppé promptly got going with plans for a tramway there, which opened in 2003. Its original design allows power to be drawn from the ground: the modern successor to studs and conduits.

Today, the Aquitanian capital is the largest city in France without a metro system. But it’s worth noting that of the cities with a metro, Paris, Lyon, Marseille and Toulouse have all developed tramways as well. Lille has modernised a line it never closed, and is looking to build more.

Capital concerns

The focus of our story being Paris, let’s rewind to the 1970s. Cavaillé initially targeted smaller cities, whose ridership didn’t justify the expense of a metro. Thus, Lyon and Marseille – both of which were building metros in the 70s – were excluded, as was Paris – which had boasted a metro since 1900 and was building its RER. But even if the city of Paris itself was already densely crisscrossed by metro lines, the same cannot be said of its inner suburbs.

In 1977, the region of Île-de-France commissioned a study into the creation of two new suburban transport lines, forming an incomplete circle passing through the inner-ring departments surrounding Paris. These departments are not what English speakers would think of as “suburban”, but rather urban in character. As such, they warranted a high-capacity transport system to facilitate both journeys between peripheral towns and connections to radial services. The obvious solution – as had been proposed way back in 1925 – was to fill this void with trams.

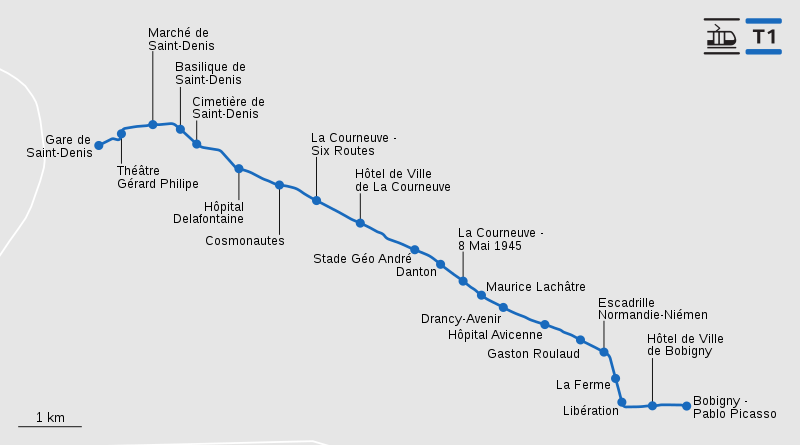

Concrete plans began to materialise in 1980, when the town planning institute commissioned in 1977 joined forces with Paris transport operator RATP to look into the first leg of the ring. This would serve the heavily urbanised zone between Saint-Denis and Bobigny, to the city’s north and east. The RATP was circumspect, fearing traffic levels would be too low to justify a tramway. But the departmental council and the local municipalities got behind the project.

In 1983, a study compared three options for the 9 km route between Saint-Denis and Bobigny: buses, trolleybuses and trams. According to the study, the higher capital expense of building a tramway would be offset within 12 years by lower operating costs. The RATP got on board. The tramway would be in service by 1988.

Not so fast

The legislative elections of 1981 had swept a left-wing coalition to power, buoyed by the arrival of François Mitterrand, France’s first directly-elected socialist president. But in 1986, the right took control of the National Assembly1, forcing Mitterrand to appoint an austerity-inclined government which sent the RATP back to the drawing board. The company evaluated its options again, finding that a bus service with dedicated lanes would be viable, and – as they’d already found – cost less initially. As before, they found that trams would work out better in the long term. But the project depended on funding from the reticent national government. The future was uncertain.

Fortunately for tram fans, this limbo didn’t last long. When Mitterrand was reelected in 1988, he promptly called new legislative elections, which brought the left back into the Assembly. The project was safe.

Work started in 1990 to build the necessary infrastructure, including bridges over the Canal Saint-Denis and the Grande Ceinture railway line, and the widening of a bridge over the A86 motorway and the RER. For rolling stock, the obvious choice was the TFS, in its Grenoble iteration. Level boarding was still a rarity in the 1980s, but Grenoble’s TFS was low-floor for 70% of its length. Not only did this make it accessible to wheelchair users, it also made boarding much faster than older designs involving steps. Since then, 100%-low-floor trams have become common, including in Paris. Other systems, like Manchester’s Metrolink, have achieved level boarding with high-floor trams by adjusting the platform height.

Stand clear of the doors

On 6 July 1992, trams returned to Île-de-France with the opening of the first stretch of line 1, running for 3.6 km between Bobigny and La Courneuve. At either end of the line were connections to the metro: line 7 had been extended to La Courneuve in 1987, and line 5 to Bobigny in 1985. From 21 December 1992, the line continued north west to Saint-Denis railway station; although it misses a connection with the RER B, it connects to line 13 of the metro and to both the RER D and Transilien H at Saint-Denis.

The tramway was an instant success, with 55000 trips per day in 1993, rising to 80000 in 2000. The naysayers were definitively proven wrong: trams had their place in the transport landscape of Île-de-France.

The consequences of this popularity were threefold.

Firstly, in order to handle the higher-than-expected footfall, the line was renovated in 2001, with notable improvements including a better passenger information system and priority at junctions. At La Courneuve, a station was redesigned to improve passenger flows.

Secondly, the stage was set for the line to be extended, with the first new station opening in 2003.

Thirdly, with trams having proven their viability in the region, it was time to start planning the next lines. Including within the city limits.

The comeback continues

Line 1 had demonstrated that trams had their place in the capital’s transport system. Line 2 would show that they could also revive old railway lines. In fact, consultation on this second line was already underway by the time line 1 entered service. We’ll find out more in part 9.

-

This was France’s first period of cohabitation, in which the presidency and the National Assembly were in different hands. Presidential elections were held every 7 years, whereas assembly members only sat for 5-year terms. A constitutional change in 2002 made this situation much less likely by reducing the presidential term to 5 years. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris