Paris has been served by many forms of transportation over the years, from the trains, trams and buses familiar to modern inhabitants to the ferries, fiacres and funiculars of yesteryear. But there are some plans that never saw daylight: the transport that never was. Over the past two editions we’ve discovered Aérotrain, the incredible hovering train that was due to whisk suburban commuters over 20 km in 10 minutes, and Aramis, the project that tried to make the dream of Personal Rapid Transit come true. In the third part of the series, we look at SK. This cable-hauled people mover has proved itself as a viable technology, with a working installation in Shanghai. But circumstances in Île-de-France were not so favourable.

What is a people mover?

All public transport moves people, but the term “people mover” is used specifically for small-scale, automated systems, such as those found in airports and theme parks. The French name is more informative: hecto or transport hectométrique, i.e. transport over distances measured in hundreds of metres (hectometres) rather than kilometres. The English name comes from a Disneyland attraction, one of the theme park chain’s many examples of interesting rail transport.

While Paris’s Disneyland doesn’t have any automated people movers, both major airports do (CDGVAL and Orlyval). The Montmartre Funicular arguably falls into the category too, meeting all parts of the typical definition: it’s small-scale, fully automated and runs on rails.

SK

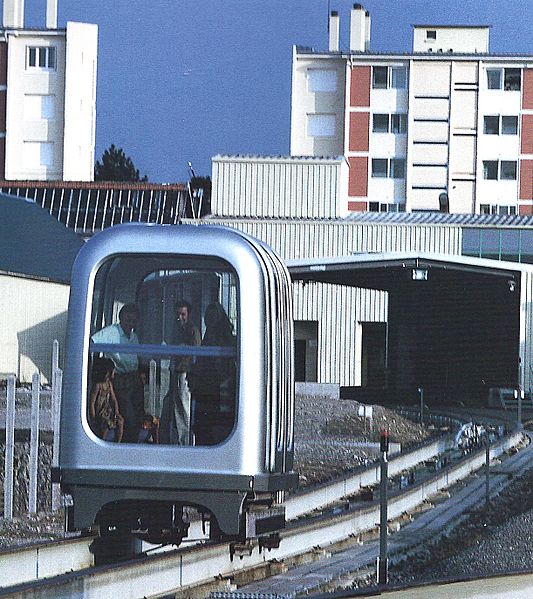

In the 1980s, transport company Soulé and inventor Yann de Kermadec developed a system based on cable-hauled cabins, which they called SK – S for Soulé, and K for Kermadec. The cabins are pulled by a cable which moves continuously at around 20 km/h, from which they detach in stations, a functioning similar to that of many cable cars. Like a cable car, the cabins themselves are small (early iterations could hold 12 people; this later rose to 29) but service is very frequent, with an interval of 17-50 seconds between cabins. They hold onto the cable using a grip under the body, a setup inspired by cable tramways such as Paris’s defunct Belleville funicular tramway and San Francisco’s still-extant cable cars.

SK has fared better than Aramis, in that it has been successfully installed in a number of places, including exhibition centres in Vancouver, Yokohama and Villepinte (north east of Paris). Today, however, just one remains: Shanghai’s strangely psychedelic Bund Sightseeing Tunnel. But three other SK lines were completed in the Paris region – at great expense, including to the taxpayer – and never opened.

CDG airport

Europe’s largest airport by area, Charles de Gaulle airport is almost a third the size of the city of Paris, at 32 square kilometres. When Terminal 2 opened in 1982, transport around this vast site was limited to buses, which could take up to 30 minutes between the two terminals. Connections to car parks and the Roissypôle transport exchange (at the time, the terminus of RER B and thus the site’s only rail connection to Paris) also suffered congestion.

In 1991, a call to tender was launched by airport operator Aéroports de Paris and the Syndicat des Transports Parisiens (STP, the regional transport authority) for the building of two lines, one to connect the two terminals to each other, to Roissypôle and to some of the site’s parking, and another to connect different sub-terminals of the expansive Terminal 2. The line connecting the terminals would measure 3.5 km; the other, 800 m.

Three proposals were studied. One was VAL, the light metro system developed for the Lille metro by Matra (the company behind Aramis) and operating there since 1983. VAL had already been chosen to link the terminals of Paris’s second airport, Orly, with the RER network. The other two projects up for consideration were both for cable-hauled people movers: SK, and the Poma 2000, operating in the town of Laon since 1989. Of the three, only VAL had proved itself over the distances required for Charles de Gaulle airport. So why was SK chosen instead?

The proposed cost certainly played a factor: SK was the cheapest of the three proposals. But the bid was also made more attractive by a partnership with RATP, the Parisian transport operator. It’s been suggested that this partnership was at the behest of RATP’s president Christian Blanc, who had a bias in favour of Soulé from his time as prefect of the Hautes-Pyrénées department, home to the company’s factory and head office.

What went wrong at CDG?

Both lines were constructed and extensive tests were run, with a view to opening to the public in 1996. This was pushed back and eventually abandoned in 1999 for reasons of reliability. SK struggled to handle the sharp curves and long distances of the 3.5 km line 1. Cabins had difficulty maintaining their grip on the cable, and the automatic systems which stopped the cable in the event of a problem were found to detect too many false positives, leading to prohibitive service irregularities. In the end, it’s VAL – initially rejected for its cost – that was chosen. It was able to reuse the platforms and stations, but the rest of the system was incompatible and had to be ripped up. By one estimate, the total cost of choosing, building, then abandoning SK stood at 2 billion francs (around €300 million, without adjusting for inflation). Soulé’s initial bid had quoted a mere 290 million (€44 million).

The cabins might never have opened to passengers, but singer Étienne Daho was able to film a music video there, with wonderful views of the futuristic vehicles in motion.

Shanghai’s Bund Sightseeing Tunnel, 647 m long, opened in 2000 and is still in operation today. It uses the SK 6000: exactly the same system as was used at CDG. Indeed, SK can work perfectly over short distances. So why did its other Parisian project – just 560 m long, with only two stops – go south?

The Noisy-le-Grand mini-metro

In the mid-20th century, the area northwest of Paris that we now know of as La Défense was inhabited by factories, farms and even slums. But from 1958 onwards, this neighbourhood was transformed into the largest purpose-built business district in Europe, welcoming 180 000 workers every day to its glittering towers. In the 1980s, a time of massive expansion for the district, one man was behind almost half of its new buildings: Christian Pellerin, “king of La Défense”. In 1988, he looked east, to the suburb of Noisy-le-Grand, with a new project: Maille Horizon.

Noisy-le-Grand is one of the 26 communes that make up Marne-la-Vallée, a new town developed from the 1960s onwards, spanning an east-west corridor some 20 km in length. At the eastern end lies Disneyland, while at the western end, in the sector known as Porte de Paris (Paris Gate), stands Noisy-le-Grand, around 15 km east of the centre of the capital. Development in Marne-la-Vallée is largely coordinated by dedicated public planning organisation Epamarne. In the 1970s, Epamarne developed the Mont d’Est neighbourhood, with a major regional shopping centre and the offices of several major companies and public bodies. The Maille-Horizon district would add 355 000 m² of new office space to the town, right next door to Mont d’Est.

In 1991, the STP approved the construction of a 560 m people mover to connect the RER station Noisy-le-Grand – Mont d’Est to the new business district. In October of that year, Soulé was given the contract to build its SK system here. This was SK’s ideal setting: a simple shuttle over a short distance. Building work launched immediately, and the line was ready by February 1993.

What went wrong in Noisy-le-Grand?

Unfortunately, the financial crisis of the early 1990s burst the property bubble that had been developing in Paris, and Pellerin’s company went bankrupt. The SK was complete, but not a brick had been laid of the offices it had been built to serve. 70 million francs (€10.5 million) had been spent on this line to nowhere. €2.2 million of this had come from the taxpayer.

In November 1994, the mini-metro was mothballed. The transport authorities were faced with a dilemma: should they shut everything down and demolish the stations? Should they simply abandon the line to avoid putting any more money into it? Or should they maintain it in case the building project was revived when the economy rebounded?

They chose the third option, ploughing a further 1 million francs a year (€150 000) into the SK to keep its cabins moving at least once a month. By 1999, the fully-functional people mover had been moving nothing but air for six years. At the time, RATP was running operations with funding from the STP. But in October of that year, the STP decided enough was enough, and cut its funding. It was the end of the road for Noisy-le-Grand’s metro.

What remains of the mini-metro?

At one point, sites across Île-de-France were being considered for SK, including a viaduct across the Pont Charles-de-Gaulle to connect the Gare de Lyon and the Gare d’Austerlitz. None of these came to pass, and the only SK system with infrastructure still in place is that of Noisy.

For two decades, the tunnel, tracks and cabins of this metro were left abandoned. In time, they fell victim to vandalism. This blog post shows the state of the system in 2006, while this YouTube video shows its decrepit condition in 2014.

In 2016, plans were drawn up for a new development project at the site of Pellerin’s. Instead of a segregated business district, the new plans – less ambitious in scale than the earlier ones, but nonetheless significant – are for a mixed-use neighbourhood, with 60 000 m² of office space, 7000 m² of shops and around 500 homes, as well as schools and local services. But there won’t be a mini-metro. In 2018, the station building for the Maille Horizon terminus was demolished. The tunnel remains, an underground memorial to the sad story of SK.

This article is part of a series about the transport that never was in Paris: see below for links to the rest of the series. And Fabric of Paris will keep coming back to stories like these, so make sure to sign up below to receive email updates.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris