A city like Paris is the result of millions of events and decisions, some big and some small. This blog exists to draw attention to the often-forgotten stories behind the infrastructure we interact with every day. Sometimes these are stories of deliberate, dramatic transformations; sometimes they are more piecemeal and unpredictable. But one thing is for sure: if we could go back 10, 100 or 1000 years and change one parameter, the Paris of 2020 wouldn’t look the same.

Every train or bus line, every alley or boulevard, every streetlight or tree or advertising hoarding exists because of a series of decisions that put it there. But what about the infrastructure that never was? What about the ideas that came close to fruition, but against whom events transpired to block them? What might Paris look like today if things had worked out differently? Over the next few weeks, with regard specifically to transport infrastructure, we’ll be taking a look at some of the projects that never made it off the ground. We’ll start with Aérotrain, an ambitious high-speed rail proposal that was due to link the commuter suburb of Cergy with the business district of La Défense. It’s a story that starts with an exciting vision for the future and ends in bitterness and death.

The hovertrain concept

At the advent of rail travel in the 19th century, trains were – by a considerable margin – the fastest way to travel. By the mid-20th century, competition from road and air travel meant this was no longer the case. To remain competitive, rail needed to get faster. Efforts in this direction were taken in a number of different countries and in a number of different ways.

One concept, investigated separately by teams in the UK, the US and France, used hovercraft technology to suspend the train above a concrete guideway. By floating above the rail on an air cushion, hovertrains could avoid the friction of steel wheels on rail, increasing speeds and decreasing wear and tear. These issues are especially bad for conventional trains at high speed, where the hunting oscillation becomes a very real problem, not only dramatically increasing friction but also creating a risk of derailment and making journeys uncomfortable. The hovertrain’s monorail was a lot cheaper to produce than steel rails, and journeys were unaffected by imperfections on the guideway.

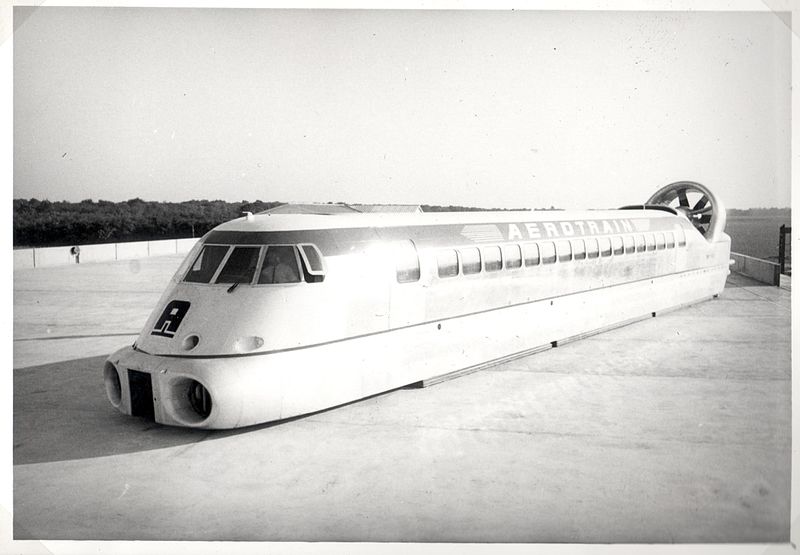

France’s hovertrain, called Aérotrain, invented by Jean Bertin in the 1960s, used a single reinforced concrete rail in the shape of an inverted “T”. Prototypes for long-distance travel used gas turbines for propulsion, eventually reaching a peak speed of 430.4 km/h (breaking rail’s record at the time) with the I80-HV. Since these were too noisy for urban and suburban use, another prototype – the S44 – used an electric linear motor and could run at 200 km/h.

Bertin hoped to get Aérotrain selected for a Paris-Lyon link, but also for suburban routes connecting cities and airports. Proposals included Marseille – Marseille Provence Airport and a route in Île-de-France connecting Charles de Gaulle and Orly airports. In the end, in July 1971, a government committee chose as its first route a line running from the new town of Cergy-Pontoise, in the outer suburbs of Paris, to the new business district of La Défense. The chosen route would be 22.9 km long and cross the Seine three times, achieving speeds of 180 km/h and completing the non-stop journey in around 10 minutes.

What went wrong?

The dream wasn’t to last. Various events and realities conspired to stop the Aérotrain from going ahead.

For long-distance travel, the technology saw competition from the SNCF’s research on the TGV, inspired by Japan’s Skinkansen and running on standard-gauge steel rails. The major advantage of the TGV over the hovertrain was its compatibility with existing railways, meaning that the TGV network could extend much further than the high speed rail lines themselves. For example, France’s first high speed line, the LGV Sud-Est, was built between the suburbs of Paris and Lyon, with trains completing their journeys to the city centres on older lines. Although the hovertrain’s infrastructure is cheaper to build, more could be saved by avoiding costly land acquisition in dense urban areas. Moreover, trains could run direct to places not connected to the high-speed network, as they do to this day to such cities as Toulouse, Nantes and Geneva.

To make matters worse, the 1973 oil crisis arrived just at the wrong time for Aérotrain. Although the first TGVs also ran on gas turbines, when oil prices rose they were able to switch to electric power, unlike the high-speed Aérotrain prototypes. For its part, the suburban prototype was propelled by electricity, but still required an internal combustion engine to create the air cushion.

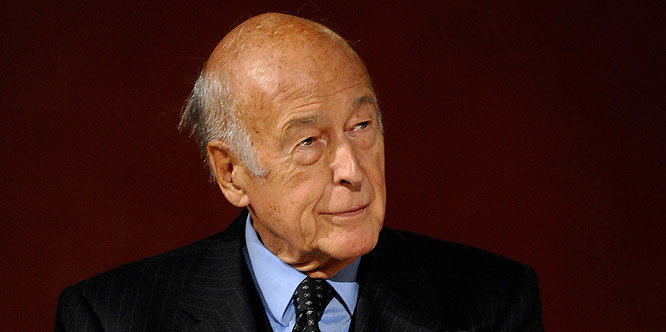

Another factor was the change in government precipitated by the death of Georges Pompidou in 1974. Pompidou’s reputation, both as Prime Minister and as President, was as a moderniser: Paris under his tenure saw such revolutionary (and often controversial) projects as the Centre Pompidou, the Tour Montparnasse, the high-rise housing developments of Italie 13, and controlled-access highways like the boulevard périphérique and the voie Georges-Pompidou. His successor in the Élysées Palace, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, was more conservative in this respect and favoured more traditional technologies.

It’s been alleged that Giscard d’Estaing’s opposition had something to do with a family link to Schneider et Cie (now Schneider Electric), which produced steel and had a financial interest in the country’s dependence on steel rails: his wife was from the Schneider dynasty. The Aérotrain from Cergy to La Défense was approved in 1974 – before being overturned weeks later after the change of administration.

All the same, it would be unreasonable to pin all of the hovertrain’s opposition on the incoming president. In Cergy itself, local voices had become increasingly sceptical as the project began to face delays and cost overruns. People were already moving in to the new town before any durable transport options were in place, and it was felt more prudent to build a railway branch line connected to the existing network. Today, Cergy is served by RER line A and Transilien (suburban railway) line L. The journey takes around 30 minutes on line A, with seven intermediate stops.

If Bertin was disappointed with the cancellation of the La Défense line, all was not lost: he received assurances from the transport secretary and interior minister that they believed in the technology and would pursue the Marseille airport project. However, the confirmation of the TGV in September 1975 signalled the final blow – if not for the technology itself, then at least for Bertin’s continued leadership. Bitterly disappointed, he stepped down from the companies he ran. Shortly afterwards, aged only 58, he died of cancer.

The Aérotrain suffered abroad as well as at home, as Bertin’s son later explained: “Every time my father went abroad to promote the Aérotrain, in Argentina, Brazil or the US, the SNCF sent a team a few days afterwards to talk it down.” The issues that it had faced in Bertin’s lifetime didn’t go away, and in 1977 the project was abandoned and the record-breaking I80-HV took its final journey.

What remains of the Aérotrain?

The Aérotrain’s first test tracks were in the Pays de Limours, in the Essonne department, some 25 km southwest of Paris along a disused railway line between the capital and Chartres. In the manner of the Coulée Verte du Sud Parisien (along the same railway line, closer to Paris), this has been turned into a greenway for cyclists and walkers. The third test track was built outside Orléans, between the towns of Saran and Ruan, to test the I80 high-speed prototypes. Some of this monorail is still standing; it’s about all that’s left of the project.

In 1991, the S44 prototype was destroyed in a fire. In 1992, weeks before it was due to be exhibited in a museum, the I80 high-speed prototype met the same fate, this time at the hands of arsonists. The culprit was never found, but some people, such as erstwhile mayor of Saran Michel Guérin, had their ideas. “The fire required 100 litres of kerosene,” he said in an interview with Libération. “You’re not going to tell me it was kids who did that!”. He blames rival companies, who he claims weren’t satisfied with the project being abandoned and “wanted the concept forgotten”. Whatever the truth of the matter, it’s a sad ending to the story.

For such an ambitious project, Aérotrain’s legacy in modern working transport is scant. The only hovertrains in regular service today are those of the Otis Hovair system, a cable-hauled people mover serving small, closed areas such as airports. For high speed land travel, development has almost entirely moved to steel rails, with notable new records set in France, Japan and, more recently, China. Maglev trains, which hover over the track using powerful electromagnets instead of an air cushion, have had more success, notably in East Asia. But they suffer from some of the same key problems: high energy requirements and poor integration with existing networks.

Jean Bertin’s business legacy survived the failure of Aérotrain, and today Bertin Technologies produces equipment for the energy, defence and pharmaceuticals sectors. But the one technology for which he is best known lives on only in the history books.

This article is part of a series about the transport that never was in Paris: see below for links to the rest of the series. And Fabric of Paris will keep coming back to stories like these, so make sure to sign up below to receive email updates.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris