Let’s start today’s article with a quick quiz1:

- Which Parisian transport network has 10 lines, 210 stations, 127 km of track and over a million passengers a day?

- Which Parisian transport network will see 4 new lines and almost 100 km of new track over the next few years? (For reference, the metro has a total length of 214 km).

- Which Parisian transport network was already carrying passengers in 1855, almost half a century before the metro?

- Which Parisian transport network once counted 122 lines and 1100 km, carrying 720 million passengers a year? (For reference, that’s almost half of the Paris metro’s pre-Covid ridership).

- Which Parisian transport network was completely nonexistent between 1957 and 1992?

If your answer to all five questions was “the Île-de-France tramway”, congratulations. Like many other cities, Paris once boasted an extensive streetcar network, but this was rapidly and unceremoniously ripped up in the mid-20th century. Like many French cities, the tram has since made a comeback, albeit in a different form and serving a somewhat different purpose. Over the next few instalments of Fabric of Paris, I’ll be telling the story of the rise, fall and rebirth of the Parisian tram. To begin at the beginning, let’s start with a look at the origins of the first network.

The early history of public transport in Paris

Early Paris was compact and walkable. The area enclosed by the Philip Augustus wall (completed in 1215) can be traversed on foot in half an hour (though it admittedly would have taken longer to navigate the medieval city’s crowded, narrow, unpaved streets). Until around this time, the only alternative to walking was horseback riding. In the 13th century, nobles began to use horse-drawn vehicles, but these were ill-adapted to the narrow streets of Paris, and Philip IV (king at the end of that century) instituted perhaps the city’s earliest anti-congestion measures, restricting their usage.

Things began to change in the early 1600s, with the first documented hackney coaches – the direct ancestor of today’s taxis – appearing in London in 1621. Within a decade, a similar service was operating out of the Hôtel Saint-Fiacre, on the rue Saint-Martin in today’s 3rd arrondissement of Paris. This gave its name to the fiacre, a word for the taxis which has survived into other languages. In Vienna, horse-drawn Fiaker are still available for hire, and have given their name to a traditional local dish, Fiakergulasch.

In 1662, French polymath Blaise Pascal created the world’s first recorded urban public transit network: the carrosses à cinq sols – five-sol coaches. These represented a major innovation: coaches would follow a fixed route, on a regular schedule, with prices (the five sol that gave them their name) charged per passenger, regardless of how full the vehicles were. Unfortunately, this service didn’t last. The Paris parliament decided to deny access to soldiers, servants and manual labourers, depriving the company of most of its customers. By 1677, public transport in Paris was dead. But a truly revolutionary idea had been born.

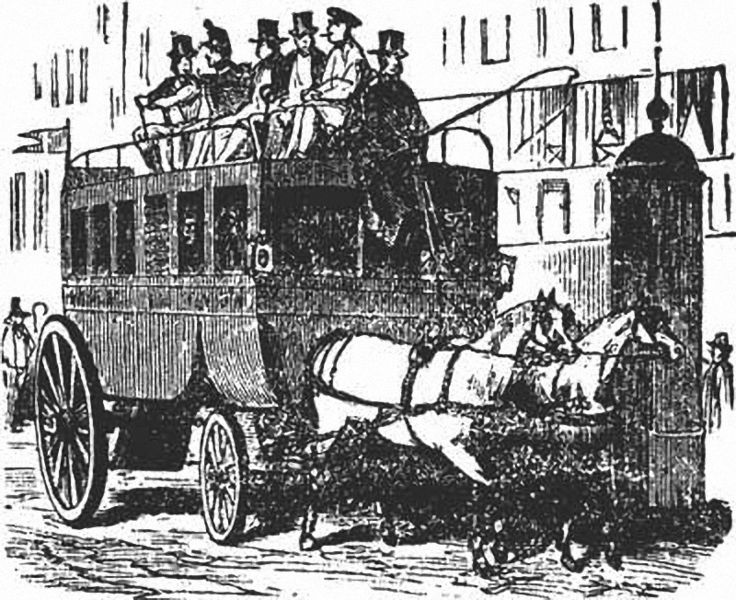

A century and a half later, in 1826, entrepreneur Stanislas Baudry created the first transport service with the name “omnibus”, in Nantes in western France. Its success led him to bring the concept to Paris, which saw its first omnibuses in 1828. This was a time of rapid urbanisation, and the nascent public transit industry burgeoned.

The first tramways

The omnibus obviously represented a significant advance over the alternatives of the time: as urban areas expanded, walking was no longer viable all the time, and not everyone could afford their own horses and stables. But these were not rubber-tyred vehicles running on tarmac, and moving large vehicles over rough paving was difficult. This was a particular problem on the mostly unpaved streets of the US.

Enter: the more efficient and comfortable rail. The first “streetcar” or “horsecar” – a horse-drawn tram – appeared in New York City in 1832. However, these rails were raised up from the ground, causing problems for other road users, and the cities of Europe, where the roads were mostly in better condition, didn’t adopt this system. It would take the innovation of Frenchman Alphonse Loubat for this technology to reach across the Atlantic.

Loubat, who lived in the US, made a game-changing invention in 1852: the grooved rail, which could be buried in the roadway so that it didn’t protrude above the surface. The success of a first line on New York’s Broadway led the tramway to take off across the USA. In 1853, Loubat returned to France and built the first tram line in Paris, along the river in today’s 8th arrondissement. His company was then awarded a concession for a line from Sèvres (south west of Paris) to Vincennes (to the city’s east): the “American railway”.

Unfortunately, this service was truncated before it began, with the city making it terminate at the Pont de l’Alma (later at the Place de la Concorde) out of fears of accidents in the denser areas further east. But after its European genesis in Paris, the tram began to take hold of the continent, conquering cities from Brussels to Berlin to Budapest.

Expansion in Paris

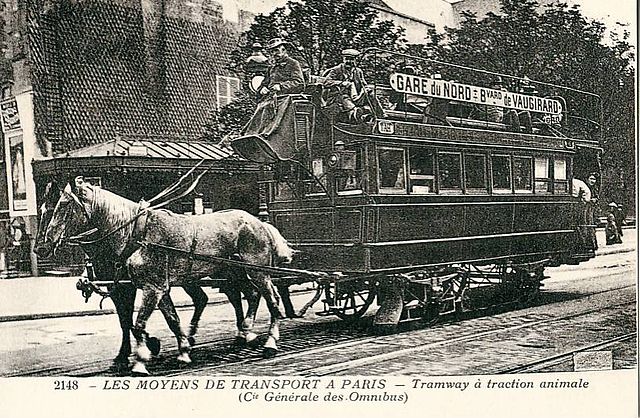

The Second Empire (1852-1870) saw a few significant changes to the Parisian public transport landscape. The lines that would form the Petite Ceinture circular railway progressively opened to passengers between 1854 and 1869. In 1855, the city’s various omnibus operators were merged into the Compagnie Générale des Omnibus (CGO), rationalising the network. But there was little tram development during this period.

Besides Loubat’s “American” line, two others were established: one between the western suburbs of Rueil-Malmaison and Port-Marly, and another between Versailles and Sèvres (where passengers could transfer to Loubat’s service). The two lines between Versailles and Paris were incorporated into the CGO. But a significant rollout of tram lines would have to wait for the fall of Napoleon III.

In July 1870, France declared war on Prussia. This war would ultimately spell the end of the Second Empire and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to the newly unified Germany. In the meantime, Paris suffered a four-month siege leading to such food shortages that cats, rats and even zoo elephants were slaughtered for their meat. By the end of this siege and the battles surrounding the subsequent establishment of the Paris Commune, the CGO had lost thousands of horses, many of these also having been killed for food. Once peace was established, the company acted fast to replenish its stables, but in their haste acquired horses ill-adapted to pulling omnibuses.

Thus far, the city authorities had been reluctant to allow rails onto the streets of the city centre. Now, however, the reduced tractive effort required to pull trams was looking very attractive. The “American” line was finally allowed to lay rails as far as the Louvre in 1873, then all the way to Vincennes in 1875. The tramways of the CGO began to constitute a real network, with the central government granting permission for eleven lines in 1873, and a further six in 1877. In addition, two new companies were created in 1873, tasked with operating in the northern and southern suburbs and connecting these with the capital.

By the time of the 1878 Exposition Universelle, Paris had a substantial (if skeletal) network, serving all of the city’s major sites. Trams would typically stop on request rather than at fixed points. With the speed of horse-drawn vehicles as it was, it was often possible to board and alight while they were in motion. Unlike today, when the only double-decker vehicles in Paris are the open-top tourist buses, most trams had two storeys.

Progress slowed after the 1878 exhibition, but a few attempts to use something other than horses for traction had already been made. By the time of the next world’s fair in Paris – the Exposition Universelle of 1889 – horses were looking like a thing of the past. But Paris’s move into more modern technologies will have to wait for Part 2.

-

Sources: Île-de-France Mobilités, Le Monde, Wikipédia ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris