Last November, we began a series on the history of the Parisian tramway with a look at the origins of public transport in Paris and the deployment of horse-drawn trams from the 1850s onwards. Then in December we explored the first attempts to move away from equine traction by employing the steam engine. Today we pick up the story in the 1880s, when another mechanical solution was tried: compressed air.

The hero of this chapter is engineer Louis Mékarski. Mékarski hailed from a quite remarkable family. His father, Jean Népomucène Mékarski, was a cousin of the last king of Poland, and participated in the November Uprising of 1830 against the occupying Russian Empire there. In 1831, amid reprisals, the elder Mékarski fled to France with his wife, aristocratic Frenchwoman Jeanne-Blanche Cornelly de la Perrière. Settling in Clermont-Ferrand, the couple had three children, of whom two, Adèle (known as Paule Mink) and Jules, were active participants in the Paris Commune. For his part, Louis appears to have been content to focus on engineering: in 1872 and 1873, while his siblings were in exile in Switzerland, he filed patents for his compressed air tram designs.

The technology

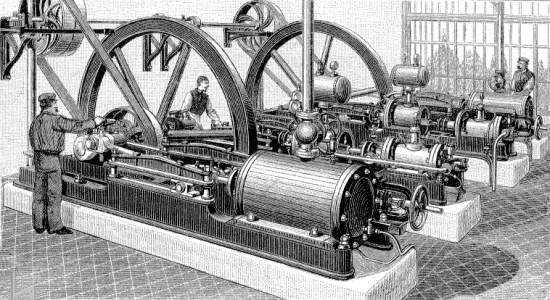

I won’t go too far into the technical details of Mékarski’s trams. For a comprehensive yet accessible treatment, see John Prentice’s series on compressed air trams. The basic principle is as follows: a compressed air engine works much like a steam engine, but with air instead of steam driving the pistons. Another power source is required to compress the air in the first place, but the steam engines for this can be located at a single site instead of on board, reducing noise and pollution in the city centre. Under Mékarski’s model, the compressed air was piped to charging stations, at which the tram’s tank could be filled via a copper tube.

The main hurdle to a successful compressed air engine is temperature change: compressing air dramatically increases its temperature, while a rapid reduction in pressure has the opposite effect. The latter problem can be of particular concern as it can cause pipework and brake lines to freeze. Mékarski’s solution to both problems involved water: a cold-water spray to cool down the hot air upon compression, and a tank of pressurised hot water carried on board vehicles to warm up the air as the pressure was released.

Compressed air vehicles were not Mékarski’s brainchild: fellow Frenchmen Antoine Andraud and Cyprien Tessié du Motay had designed one in 1840. But the concept had lain dormant for 30 years. In 1875, Mékarski first put his own designs into practice with a narrow-gauge prototype in the eastern suburbs of Paris. The following year, he presented his work in Nantes, where in 1880 the world’s first public compressed air tramway opened. These trams, in service until 1917, carried 17 seated passengers, with standing room on an open platform for a further 12. At its height, the Nantes compressed air network comprised 94 trams.

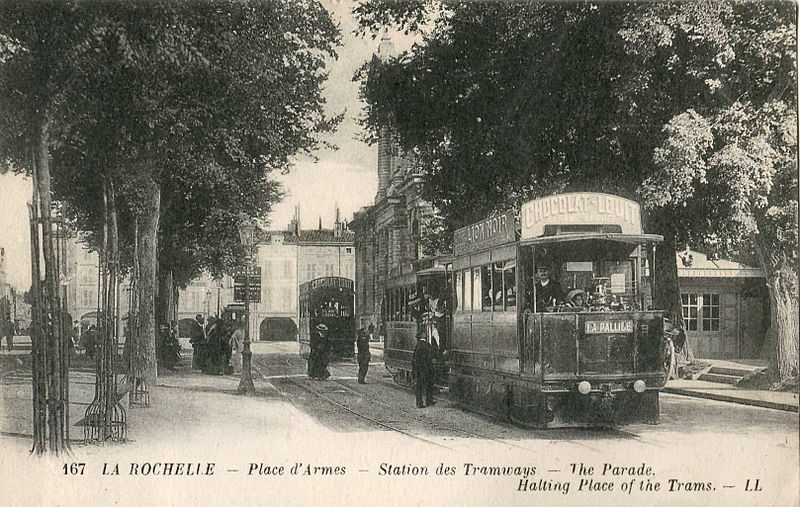

The technology soon conquered other cities, including La Rochelle and Vichy, where they were still in use until the late 1920s. It was also exported to Bern, Switzerland, where Mékarski trams ran for 11 years.

Paris

In the 1880s, Mékarski took his technology to Paris. The transport network in the capital was rapidly developing, especially with the upcoming Exposition Universelle of 1889, and Louis was able to demonstrate success in Nantes, so he had no trouble obtaining a concession to run a line in the eastern suburbs. 11.6 km long, the line opened in 1887, running east from Vincennes. Known as the Chemin de Fer Nogentais (CFN, for Nogent railway, after a major town it served), it ran open-top double-decker trams capable of towing one or two trailers. Over the next several years, two branches were added and it was extended to the Porte de Vincennes at the edge of Paris. In 1890, the CFN carried almost 1.3 million passengers.

A little downstream from Nogent, just south west of the Bois de Vincennes, the Marne forms a loop encircling the suburb of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés. The local government of this residential town lobbied for the Compagnie Générale des Omnibus – the bus and tram company serving Paris proper – to extend one of its lines there from Charenton-le-Pont. But the CGO wasn’t interested. Eventually a new company was created, the TSM (Tramways de Saint-Maur), with a single line, 8.6 km in length, opened in 1894. Following the success of Mékarski’s trams in Nogent, this new line was equipped with similar compressed air vehicles. Two new lines were constructed later that decade, but none was able to attract a high ridership and all ran at 30-minute headways. The TSM failed to turn a profit.

One of the later TSM lines attempted another compressed air technology: the Popp-Conti low-pressure system. This opened in 1898, but performance was very bad and the trams were soon replaced by Mékarski vehicles.

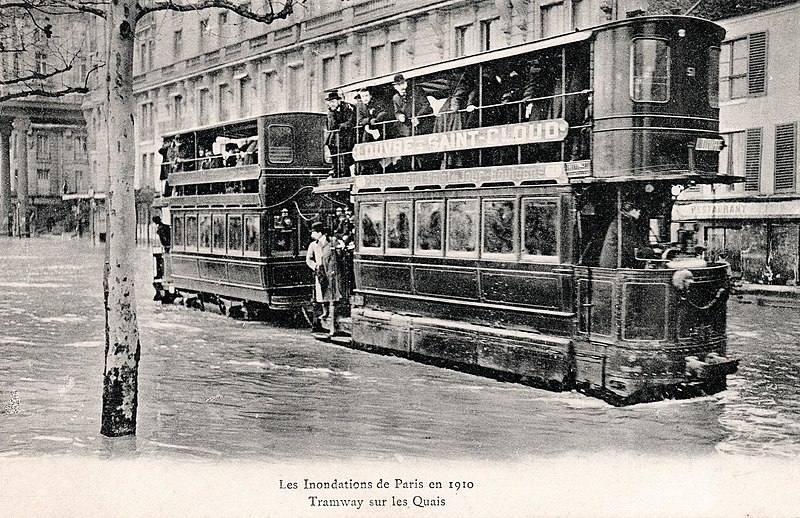

In Part 2 of this series, we witnessed the CGO’s reluctance to adopt mechanical traction on a large scale. By the mid-1890s, two of their lines were steam-powered, but the rest ran with horses. That changed in 1894, when they began running Mékarski trams between the Louvre and Saint-Cloud; they would later introduce them on a second line, between the Louvre and Versailles.

In 1895, the city of Paris banned steam trams from operating within its limits during the day. This impacted the Paris – Arpajon line, which had begun operating the previous year. Its steam-hauled freight trams, which carried food from the farms of Île-de-France’s rural south to the Les Halles food markets in the city centre, were allowed to continue operating, but only between the hours of 1 and 4 am. The line’s passenger trams separated in two at the Porte d’Orléans at the edge of Paris, and were hauled for the remainder of their journey by Mékarski engines.

Decline

In 1900, the CGO began running Mékarski trams on 8 more of its lines. But the region’s other operators were already replacing their compressed-air vehicles with electric trams. The same year, the TSM merged with another local operator to form the Tramways de l’Est parisien, which promptly switched to electricity. By the end of 1900, the CFN had also made the change. The following year, the Paris – Arpajon line adopted electricity (though retaining steam south of Antony). The network’s only remaining Mékarski trams were those of the CGO, which would subsist until 1914.

In a few places, Mékarski’s engines outlived their inventor, who died in 1923. The longest survivors were those of La Rochelle, which clung on until that city’s single line was closed in 1929.

Compressed air trams represented a significant step forward from horsecars, and were better suited for urban services than dirty, noisy steam engines. They also didn’t require overhead cables, which the central city would never accept. But once an adequate workaround for this issue with electrification had been found, electricity would claim supremacy over every other form of traction. For the time being.

In the next instalment, we will look at the last remaining mechanically-powered tramway within the city walls: the unique Belleville funicular tramway. Then in Part 5 we will finally tackle head-on the subject around which we have been dancing for so long: electrification. Be sure to subscribe to email updates below so you don’t miss the rest of the series.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris