Last time, we looked at the flourishing of Paris’s tramways in the 1920s. Several rounds of rationalisation and modernisation had created a unified network of electric tramways covering 1100 km in the region. By 1928, trams were carrying hundreds of millions of passengers every year. But as little as a decade later, only a small rump network in Versailles would remain. By 1957, the region would be entirely bereft of trams. What happened?

The internal combustion engine

To trace the decline of the tramway, let’s rewind to its very early days. While the first tracks were being laid in Paris and its suburbs, work was already underway on the technology which would prove its downfall: the internal combustion engine.

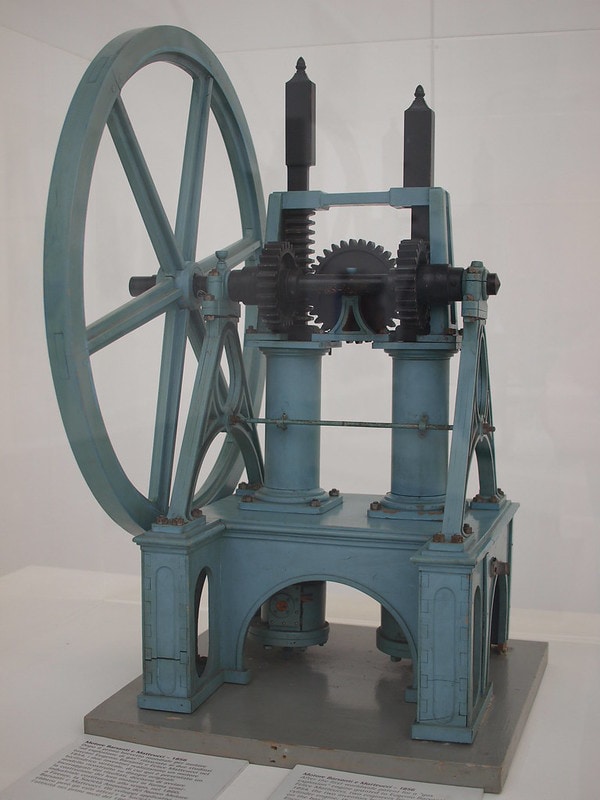

While the first internal combustion engines were developed as early as the 1790s, it’s in the 1850s and 1860s that progress really started to gather steam. Just as Paris was welcoming its first horsecars, engineers elsewhere in Europe were filing pioneering patents: first Italians Eugenio Barsanti and Felice Matteucci, and then Belgian Etienne Lenoir. In the 1870s, as Paris made its first forays into mechanically driven trams, Austrian engineer Siegfried Marcus developed a petrol-driven vehicle, while Germans Nicolaus Otto and Carl Benz further developed the engine.

This series has already discussed Paris’s 1889 Exposition Universelle, which spurred significant progress on the city’s tramways. But those were by no means the only innovation to feature at the Exposition. Also on display were Carl Benz’s Patent Motor Car and Gottlieb Daimler’s four-wheeled wire-wheel car.

In 1893, Benz began producing a four-wheeled automobile with two seats, known as the Victoria, of which 85 units were sold. The following year, this gave way to the first mass-produced car. Over the next eight years, the Benz Company would produce 1200 of this model, called the Velo.

The motorbus

What if the internal combustion engine could also power larger vehicles? It didn’t take long for Carl Benz to answer that question. In 1895, he mounted an engine on an eight-seater landau and supplied it for a route in western Germany. By 1898, he was making 12-seater buses for Llandudno, Wales. The same year, Gottlieb Daimler supplied a double-decker bus to London capable of carrying 20 passengers.

In Paris, the first motorbuses arrived in December 1905 for the Salon de l’automobile. As part of a contest launched by Paris omnibus operator the CGO, nine different prototypes ran on a special line for the duration of the two-week car show. French company Schneider & Cie (today Schneider Electric) won the contest with its Brillié P2. Modelled on earlier horse-drawn buses, the P2 had a lower deck for first-class passengers and a covered but open upper deck for second class.

In June 1906, the first bona fide motorbus line began operating between Montmartre and Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Its ten vehicles put as many as 194 horses out of work. But these were just the first of 151 P2s ordered by the CGO, rolled out progressively over the next two years.

After a bus toppled over on the Place de l’Étoile, later models dispensed with the second deck. But the motorbus was here to stay. In 1913, the last horse-drawn omnibuses were retired.

The car takes hold

In the 1890s, family-run manufacturing company Peugeot began producing motorcars modelled on Daimler’s wire-wheel car. Later that decade, Louis Renault founded his automobile company in Boulogne-Billancourt, just outside Paris. By 1900, these were part of a large and growing ecosystem of car manufacturers, counting 30 companies. By 1903, almost half of the world’s cars were being produced in France. Though dreadfully slow by today’s standards, and already considerably slower than rail, the private car offered the freedom to go wherever there was a road – and to do so with only friends for company. However, with global production only numbering in the tens of thousands annually, cars were luxury items only available to a select few.

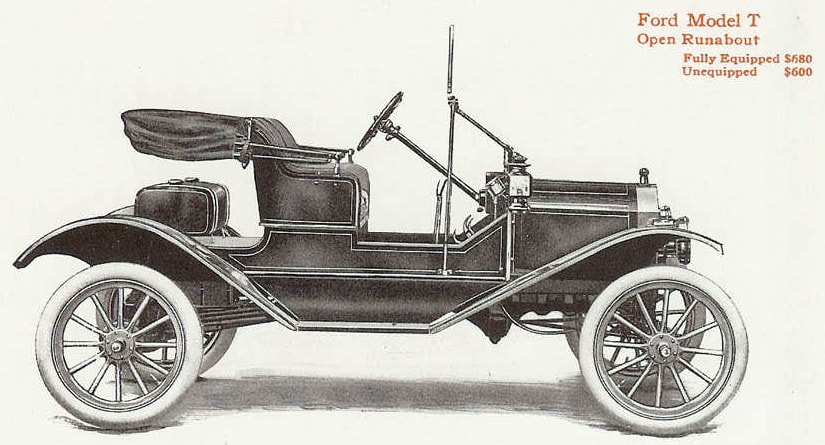

It’s in the United States that that started to change. In 1908, Henry Ford debuted his Model T. Produced on a moving assembly line, the Model T is widely considered the first affordable car. Within twenty years, 15 million units had been produced.

Renault and other French manufacturers were quick to adopt Ford’s approach. As France recovered from the First World War, the car became an affordable accessory for a growing middle class. By the early 1930s, the country boasted almost 1.5 million cars, a number higher than that of the UK and nearly three times that of Germany. But the numbers were just a part of the story. Equally important was what the car symbolised. Freedom. Modernity. Upward mobility.

For its part – despite the modernisation efforts of the 1920s – the tram was starting to look rather passé.

The first banishments

As early as 1921, the prefecture of the Seine department (covering Paris and its inner suburbs) was already looking at ways to improve traffic conditions for the city’s private cars. Removing tramways from narrow streets and replacing them with buses in shared traffic looked like a viable plan.

In 1924, the Belleville funicular tramway was replaced by a bus line. This made sense on this particular route, characterised as it was by 19th-century technology, a steep hill, and a twisting route only wide enough for one track. It also made sense on some shorter suburban routes, whose limited ridership no longer justified tramway infrastructure. Several such lines were converted from 1925.

Not all the early attempts to replace trams with buses were so successful. A 1926 experiment in Passy in the city’s west found buses lacked the speed and power of their railed counterparts. But elsewhere, some rails were removed without replacement: either their trams were diverted elsewhere or the lines were cut short.

By the end of the 1920s, aided and abetted by an automobile-friendly press, the mood of the day was clear: trams were out. Cars and buses were in. In 1929, the municipal council voted to remove all tramways within the city limits within the next five years.

Several factors contributed to this extreme decision. When trams first took hold, they were vastly superior to buses in terms of speed, reliability, capacity and ride comfort. By 1929, motorbuses were achieving decent speeds, and reliability was improving with each new model. Rubber tyres, introduced to the fleet from 1924, made the ride somewhat more pleasant. On low-ridership lines, buses, which are easily diverted when necessary and can steer around obstacles, were now a viable option.

Buses still couldn’t compete with two- and three-car trams on routes that required higher capacity. But for intra-Paris journeys, there was the metro. Besides, the car was the transport of the future. According to the new orthodoxy, the best way to improve transportation was to expand road space for private vehicles. In any case, the council had always disliked unsightly overhead wires, and would seize any opportunity to remove them.

Death spiral

Since 1921, trams and buses in the Paris region had been operated by the STCRP, a public company which unified a previously disjointed system of private operators. Throughout the 1920s, the STCRP had invested significant time, effort and money in homogenising and modernising the region’s tramways. Reluctantly, they now had to set about replacing trams with buses and refitting depots.

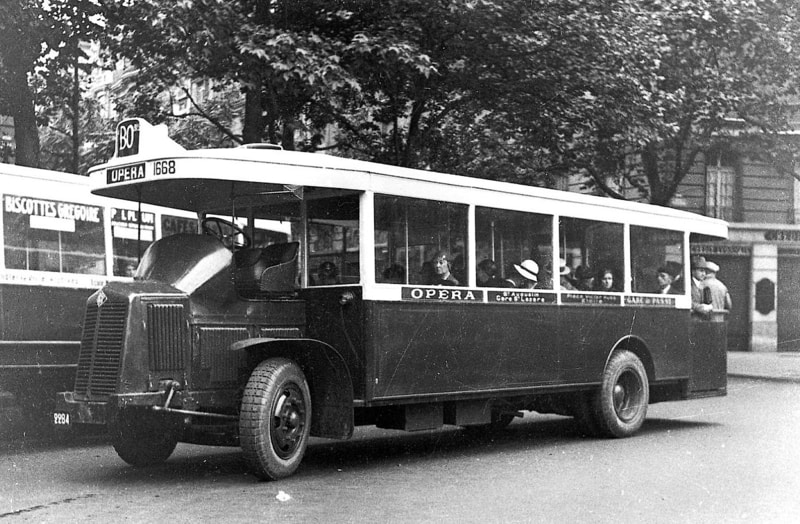

In 1926, the STCRP operated some 3000 trams and 1200 buses. In the early 1930s, they ordered nearly 2000 new buses. Renault supplied most of these, but was unable to meet the demand alone. To make up the difference, the STCRP called on another French manufacturer, Panhard.

The first tramways to be ripped up were in the affluent west of the city. But it’s worth noting that even here, where car ownership was higher than elsewhere, the disappearing trams had had good ridership figures.

The purge continued regardless. The centre, around Les Halles, was next on the chopping block. Then attention turned to the many lines linking the city centre to the suburbs.

To begin with, the suburb-city lines were cut back, rather than completely removed. Passengers would change from tram to bus at the city limits. But now, column inches in the local press were filled with complaints, deploring these forced transfers. Why not just run buses the whole way along – with the happy side effect of creating more space for cars? Never mind the fact that suburban tramways were mostly segregated and could thus bypass traffic, whereas buses had to share the road.

In 1932, the council of the Seine department made its fateful decision: trams were to disappear entirely. The STCRP, its hands tied, obliged. Six years later, on 14 August 1938, the last line was closed.

What happened to the trams?

The sudden decision to destroy the tramway so soon after a period of investment left the STCRP with a surplus of hundreds of trams in excellent working condition. A few of these were sold off to other French cities. But most of them were stripped for parts. Similarly, many of the rails, conduits and overhead lines that were taken apart were almost brand new. This was no “managed decline”: it was a rapid about-face. One could argue that it amounted to state-sponsored vandalism.

The Versailles network

After 1938, a separate network centred on the far-flung suburb of Versailles continued to chug along. But it was already in terminal decline.

Since the mid-1920s, the Versailles tramway had counted seven lines. In 1937, one of these was replaced by a bus line, and another scaled back. After the Second World War, four lines remained. But the end came on 3 March 1957. In a grand celebration amassing thousands of locals, the remaining lines were replaced with buses. The future had arrived. There would be no more trams in Île-de-France.

The end?

The most shocking part of this story is the haste with which the local authorities reversed decades of development. This wasn’t a case of putting a struggling network out of its misery. When the municipal council decided to axe the tramway, ridership was at an all-time high.

As I’ve already touched on, switching lower-ridership lines to buses probably wasn’t such a bad idea. But it would have been entirely possible to convert some lines, while keeping others active as tramways. A primary example: tramways connecting major suburban populations to the metro. Many of these were entirely segregated from traffic. Many of the new lines introduced since the 1990s fit exactly this model.

Paris’s pivot to car dominance is by no means unique. Tramways across the United States and western Europe were ripped up in the mid-20th century. Many other cities embarked on highway programs that carved up historic neighbourhoods and even filled in canals. But in central and eastern Europe, there are dozens of tramways which have existed continuously since the 19th century. Paris’s choice was not inevitable.

Fortunately, it also wasn’t irreversible. Like the proverbial phoenix, trams would return to Île-de-France after a 35-year absence. This rebirth will be the subject of part 8 of this history.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris