Funicular. Isn’t that a lovely word?

Funiculars are lovely things.

If you’re unfamiliar, here’s the basic idea: on a railway set on an incline, two cars are coupled together by a cable, such that when one goes down, the other goes up. In this way, each car acts as a counterweight for the other – the vehicle travelling uphill is prevented from sliding backwards, while the downward-bound car is prevented from running away. When the cars are of equal weight, the only external energy required is to overcome friction and air resistance; when the downward-moving car can be guaranteed to be heavier than its counterpart – as in a water-powered funicular – no engine is necessary.

Funicular is a lovely word. So lovely that many hill railways use the word to describe themselves, even when that isn’t entirely accurate. A classic example is Paris’s Montmartre Funicular, which ran for almost a century as the real thing, but has consisted since 1991 of two parallel inclined lifts: the cars are not coupled together, but each is balanced by a counterweight, allowing them to operate independently.

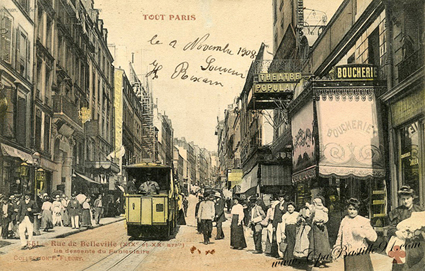

Another example, and the subject of today’s article, is the Belleville funicular tramway, which operated in northeastern Paris between 1891 and 1924. This was similar to a funicular insofar as it operated on a hill and the trams were hauled by cables. But technically speaking, it was a cable tramway. Americans would have called it a cable car, but here in Europe, that term means something else (something our North American friends call an aerial tramway).

Now that we’ve addressed the misnomer – and you’ve indulged my love of funiculars – let’s go back to the late 19th century, where our series on the history of the Parisian tramway left off. As you’ll recall, the first trams in the city were horse-drawn, but even as this first generation proliferated in the 1870s, the great minds of the day were already thinking about alternatives to animal traction.

When the network of horse-drawn, steam and compressed-air tram lines began to spread its steel tentacles across the capital, it was inevitable that the densely populated north east would fall under its grip. But the neighbourhood of Belleville posed a particular problem, in the form of one of the city’s steepest hills.

A brief history of Belleville

Although its first known residence dates back before the ninth century, Belleville would spend its first millennium as a peripheral village, some distance from the centre of action. But over the centuries, the boundaries of Paris gradually pushed further and further out, until, by the late 18th century, the village was just outside the city wall. Then came industrialisation, which swelled the eastern suburbs, Belleville chief among them. No longer a backwater, this was now a key part of the Parisian agglomeration. And it would soon become a part of Paris itself.

In the 1850s, Haussmann’s renovations destroyed thousands of working-class residences in the city, displacing tens of thousands of people and further swelling the population of the inner suburbs. By 1860, Belleville was the 13th most populous commune in the country, with 70000 inhabitants. But that year, the municipality was entirely subsumed into Paris, becoming part of the 19th and 20th arrondissements of the newly expanded and reorganised city. After several generations of dramatic change for the area, Belleville was ready for another transformation. It was ready for modern public transport.

The geographical challenge

By the 1880s, Paris’s fledgling tram network already covered a significant part of the city. But the hilly terrain of Belleville – second only to Montmartre in elevation – made conventional trams a difficult proposition in the neighbourhood. The rue de Belleville, which runs from the one-time boundary of Paris into the heart of the district, features a slope of up to 7%. Later, electric tramways elsewhere would manage such gradients and more. But it was too much for the technology of the time.

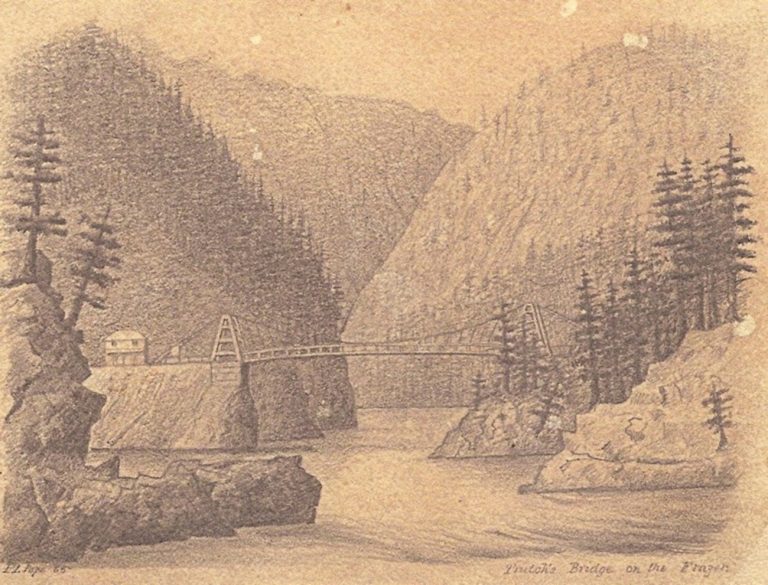

Fortunately, a solution had already been successfully deployed half way around the world. Though not technically the world’s first cable railway, the San Francisco Cable Car is the best-known predecessor to Belleville’s line, and bears more similarity than the earlier railways.

The technology

In 1835, London-based Scottish inventor Andrew Smith acquired a patent for wire rope, which he successfully applied in shipbuilding and on the railways. In 1836, he welcomed a son into the world, giving him the quite uninventive name Andrew. The younger Andrew would append an uncle’s surname to his own – becoming known as Andrew Smith Hallidie – presumably to distinguish himself from his father. But it is his father’s invention that would propel his career.

In 1852, at the height of the California Gold Rush, the two Andrews set sail from London to the United States, the elder Smith hoping to get in on the mining action there. The father was underwhelmed, leaving the following year; but his son remained, replacing the unreliable hemp rope used to lift ore out of the mines with longer-lasting wire rope. Before long, he left mining behind and moved to San Francisco, opening a factory to produce his signature cables. Hallidie employed these extensively in bridge building, and in 1867 invented a kind of continuous ropeway for goods, which proved useful in mines.

The first cable tramway

According to one story, the cable car was conceived in a single dramatic event in 1869. Unable to make it to the top of a steep, slippery San Francisco hill in rainy weather, a horse-drawn vehicle plummeted backwards, killing five horses. Witnessing this, Hallidie told himself that there had to be a better way. But it was in fact another man (a certain Benjamin Brooks) who obtained the first franchise for a cable tramway in the city, in 1870: Hallidie only got involved when Brooks failed to find funding and sold him the franchise.

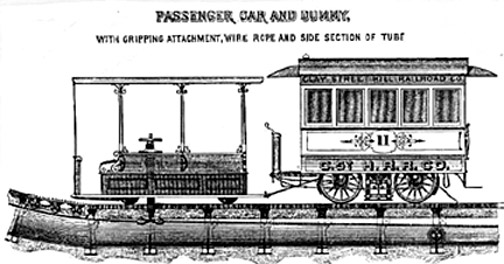

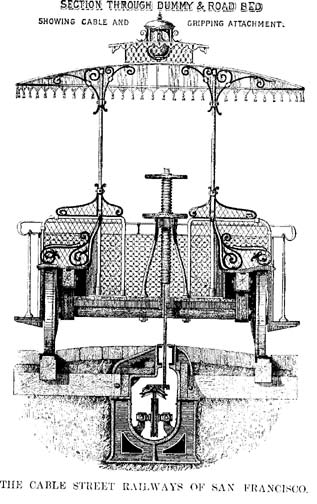

What’s undoubtedly true is that Hallidie put his expertise to work on the new tramway. For example, the Clay Street Hill Railroad featured a grip wheel much like that used in his ropeways. But he didn’t do it alone: several of the patents acquired for this new line bore the name of engineer William Eppelsheimer.

The Clay Street line – the world’s first street-running cable railway – opened in 1873.

Expansion

By 1890, the Clay Street Hill Railroad was just one of 23 cable car lines in San Francisco. The specifics varied from line to line, but each operated on the same principles: a steam-powered wheel at one end turned continuously, driving a cable running in a channel under the street. The trams moved by gripping onto the cable, and stopped by releasing it and applying brakes. The steam engines have since been replaced by electric motors, but apart from that the same setup continues to be used on the city’s three remaining lines. (It’s also the principle behind the much more recent SK, the ill-fated people mover technology we covered in a previous article).

While the network was being rolled out in San Francisco, the technology was also taking root around the United States and elsewhere. The pioneer in Europe was London’s Highgate Hill Cable Tramway, opened in 1884.

The Belleville line

In the 1880s, Belleville was fast becoming the only part of town without a tramway, despite being a populous working-class neighbourhood. Paris was getting ready to host a world’s fair in 1889. France – its national pride wounded by the loss of territory to the Prussians at the beginning of the previous decade – wanted to show it could rival the great industrial powers of the day. In 1886, at the request of an engineer by the name of Fournier, a public inquiry was launched into the value of a cable tramway to run up the rue du Faubourg du Temple and the rue de Belleville from the Place de la République.

The city gave Fournier the concession. Work on what would be the first cable tramway on the European continent was overseen by the city’s engineer, Fulgence Bienvenüe.

Unlike the roads of San Francisco, the streets followed by Belleville’s tramway were narrow: too narrow for double tracks. Instead, the line ran on a single track with five passing loops at crossroads along the route. For this reason, trams couldn’t be evenly spaced, running instead in convoys so that several could pass at once.

The Belleville funicular tramway opened in May 1891 and was an instant success. In 1902, it carried more than 5 million passengers: quite a feat for a line barely 2 km in length. But that was a record it would never break.

The upgrade

The cable was driven by two steam engines near the top of the line on the rue de Belleville. These would persist in Paris until the closure of the line, even as San Francisco modernised its network with electric power. One reason the Parisians didn’t make this change is because the powers that be – Bienvenüe among them – were already plotting the funicular’s demise.

In 1895, Bienvenüe and fellow engineer Edmond Huet proposed a new underground metropolitan railway. In 1898, the first six lines of this network were approved. By 1910 – a year ahead of schedule – all six were in operation. So successful was this initial rollout that in 1909, three new metro lines were proposed. Two of these would be in service by the outbreak of the First World War. But one was proposed which would run from République to the Porte des Lilas. This would follow the Belleville tramway for its entire length, completely superseding it.

It seems the people of Belleville valued their tramway and didn’t want to see it taken away. Their protests managed to delay the new metro line’s arrival until war put the brakes on the project. But the metro had arrived in Belleville, thanks to lines 2 and a branch of line 7 (now the 7bis). The funicular’s ridership fell as a result.

By the early 1920s, the cable tramway was old and struggling, with frequent breakdowns. In 1922, the municipal council picked up the plans for a metro line, this time continuing south west of République all the way to Châtelet in the heart of the city. In the meantime, in 1924, a temporary replacement bus service was instituted. This temporary situation was renewed several times, until in 1925 the Belleville funicular was officially cancelled. With it, steam power departed from Paris’s tramways for good.

It took some time to finalise the route of the new metro line, but work began in 1931, and line 11 opened in 1935, from the Porte des Lilas to Châtelet. A direct successor to the tramway, the metro line’s central section follows its exact route.

Today

Bus number 20 follows the route of the funicular even more closely than metro line 11 – but only in the downhill direction. If you board at Jourdain and alight at République, you’ll be following in the footsteps of thousands of 19th-century commuters.

The wider story of Parisian tramways was far from over with the demise of the Belleville line. In the next part of this series, we’ll look at the arrival of electric trams in Paris. We’re not even half way through the series, but from this point forward every tram we encounter will be powered by this revolutionary technology. Sign up for email updates below to make sure you don’t miss the next instalment.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris