In Part 1 of our series on the history of tramways in the Paris region, we looked at the precursors of the tram, from Blaise Pascal’s 17th-century carriages to the arrival of Stanislas Baudry’s omnibuses in 1828. We then saw a network of streetcar lines opening up in the latter half of the 19th century. But although horses would continue to tow Parisian trams well into the 20th century, horse-drawn streetcars were already looking rather anachronistic in the 1870s.

Steam was already well-known and well-used in public transport. Steam-powered passenger boats had begun operating on the Seine as early as 1825. All of Paris’s major terminal railway stations were established in the 1830s and 1840s. Passenger services were running on the forerunners to the Petite Ceinture from 1854. Elsewhere, London’s pioneering Metropolitan Railway – a major inspiration for its namesake network in the French capital1 – was running steam trains for short-distance inner urban travel in 1863. So steam must have seemed like a natural choice for mechanising the tram network.

First puffs

The city’s first foray into steam trams came in 1875. The Compagnie des Tramways Sud, responsible for the network in the southern suburbs of Paris, trialled a tram consisting of a single double-decker carriage, pulled by a small locomotive. The following year, regular services began between the Gare Montparnasse and the Place Valhubert, near the Gare d’Austerlitz. The engines were provided by Merryweather & Sons, an English company known for its steam-powered fire engines. In 1877, another English company, Hughes’s Locomotive & Tramway Engine Works, entered the fray, with its locomotives used on a line from Bastille to Saint-Mandé, also operated by Tramways Sud. But these were both short-lived: the steam vehicles required a staff of two per vehicle, which proved too expensive. Horses returned to both lines in February 1878.

The Compagnie des Tramways Nord, which operated in the northern suburbs, also had its share of false starts in steam traction. Starting in 1877, the company operated locomotives supplied by Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works, on loan from Geneva, between the Place de l’Étoile and the suburb of Courbevoie. These more powerful engines could each pull two coaches, but the trials met with too many technical issues and were abandoned in 1882.

For its part, the CGO, which operated buses and trams in the central city, was more conservative, sticking with horses in these early years.

Paris – Saint-Germain

One of the region’s earliest tram lines, in the western suburbs between Rueil and Marly-le-Roi, was better suited to steam. As we have seen, it wasn’t cost-effective to employ two people to operate a steam-powered locomotive pulling a single car. But this line’s footfall justified longer trains, with two passenger carriages and even a luggage car. Furthermore, this line’s more widely-spaced suburban stops stood to benefit more from the higher speeds afforded by steam.

The engines used for these trams were distinguished by being fireless: French-born American Émile Lamm had invented an engine which could work with steam produced outside the vehicle and loaded into a reservoir. Lamm’s vehicles were operated in the American cities of New Orleans, St Louis and New York; in France, a version of Lamm’s engine perfected by engineer Léon Francq was chosen. Unlike the failed attempts closer to the city centre, these steam engines would prevail here for over a decade, right up until the line’s extensions westward to Saint-Germain-en-Laye and eastward to the Place de l’Étoile in Paris.

Once the line was extended, the fireless engines reached their limits, and in 1891 they were replaced for part of the route by more conventional – and more powerful – steam engines.

The 1889 Exposition Universelle

Each of Paris’s world’s fairs, known in French as Expositions Universelles, has spurred progress in public transport. 1889 (most famous for the construction of that most notable of Parisian icons, the Eiffel Tower) was no exception. In time for this exhibition, the Petite Ceinture was entirely grade-separated, with the construction of some beautiful bridges.

The CGO’s circumspection towards new tram technologies, while understandable, represented a problem for the Exposition, which was supposed to show the world France’s technological prowess. In time for the event, they put in place a line to shuttle passengers from the Petite Ceinture2 to the Trocadéro, a distance of just over 1 km, running three vehicles along the route. The engines used were designed by engineer William Robert Rowan for use in Copenhagen; the design had also been used in Stockholm and Berlin.

After the Exposition, these trams ran between Trocadéro and Pigalle, but they didn’t last long within the walls of Paris, and were banished in 1891 to the inner suburbs, running between Auteuil and Boulogne.

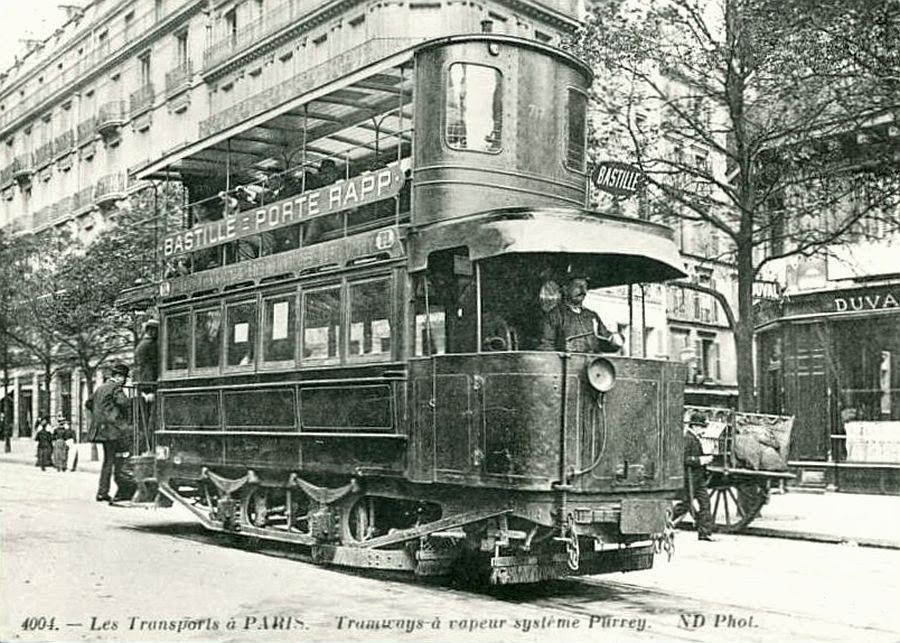

Warming to steam, the CGO would later order steam trams from Valentin Purrey, an engineer from Bordeaux who had created a successful engine while working in Barcelona. Ultimately, 160 Parisian trams would come to be hauled by Purrey’s engines. Globally, one Purrey tram is still running today, in Rockhampton in Queensland, Australia.

Paris – Arpajon

The southern suburbs played host to a unique tram line, or, officially, an “on-road railway”: the “Chemin de fer sur route de Paris à Arpajon”. As of the early 1890s Arpajon, today in the outer suburban department of Essonne and still surrounded to the south and west by fields, was at the centre of an important area of market gardens. The new railway was set up to transport the region’s produce to Les Halles in the 1st arrondissement, where a vast wholesale food market then stood. Because no railway penetrated centrally enough to serve Les Halles, it was decided that a tramway could be used instead, integrating with the already-existing network within the walls of Paris.

Freight tramways are rare today, but planners have begun to pay attention to them recently as a low-carbon, low-pollution alternative to diesel lorries. Dresden’s CarGoTram, for instance, has been running since 2001, carrying car parts to a Volkswagen factory; Zurich has the Cargo-Tram, used for waste collection. In France, the TramFret concept, trialled in Saint-Étienne, sees passenger trams refitted for freight and running along regular tram lines in off-peak hours. The passenger tram fell out of favour for many years before making a comeback at the turn of the century; perhaps the cargo tram is destined for the same change of fortunes.

The Paris – Arpajon line wasn’t limited to freight traffic. In fact, the City of Paris didn’t allow freight trams within its walls except between 1 am and 4 am. Passenger services, which terminated at Odéon on the left bank, were also steam powered, but Paris forbade this in 1895, shortly after the line’s opening, as well as restricting the length of vehicles. Trains arriving at the Porte d’Orléans were split in two, with each half hauled for the remainder of its journey by a compressed-air engine. But that can wait until Part 3.

Full steam ahead?

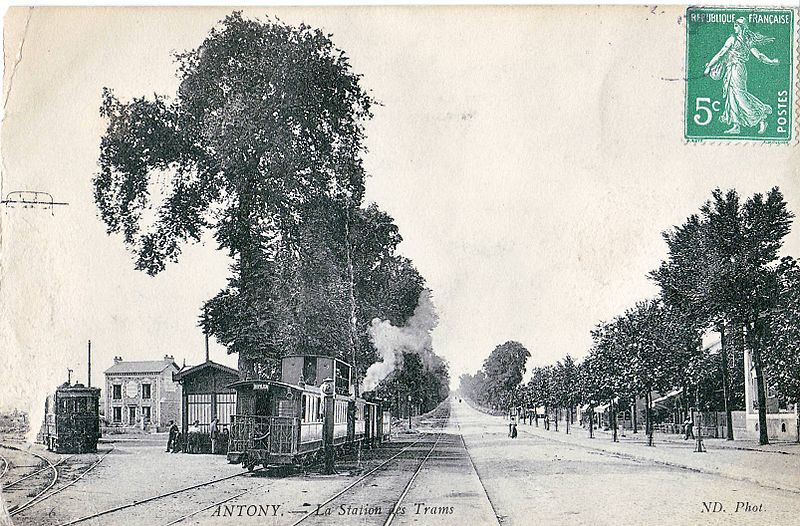

In Part 3, we’ll look at another technology that briefly saw use on the Parisian tramway: compressed air. Less noisy and polluting than steam, but ultimately more expensive and less efficient than electricity, this mode of traction was in use somewhere on the network between 1887 and 1914. Steam would survive for several decades, primarily in the suburbs. South of Antony, the Paris – Arpajon line would continue to rely on steam until the line’s removal in 1937. Within the city walls, one line drew its power from a steam engine, though the vehicles themselves didn’t carry engines of their own: the Belleville funicular. We’ll cover that in Part 4. Then Part 5 will finally bring the most important technology into the spotlight: electricity. Make sure to sign up to email updates below so you don’t miss the rest of the series.

In the meantime, Fabric of Paris will mark the New Year with a look back at the city’s transport developments in the past year. Until then, take care!

-

Paris’s metropolitan railway, or Métropolitain, wouldn’t appear until the turn of the century, but the first proposals for a Parisian metro date back to the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War. ↩

-

The station on the Petite Ceinture was then called the Gare du Trocadéro; today it’s the Avenue Henri-Martin on line C of the RER. It holds the dubious distinction of least-used SNCF station within the city limits. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris