Earlier this year, I posted a list of my favourite bridges over the Seine in Paris. But while the city’s most famous bridges undoubtedly cross the river, these represent barely a tenth of the total number, which stands somewhere north of 300 (with around half of these belonging to the boulevard périphérique). Though many of these are rather nondescript, there are a few gems. In this article and the next, I’ll be listing my top ten.

10: Pont Caulaincourt

Most bridges, in Paris as elsewhere, cross water, railways or roads. But the Pont Caulaincourt carries a road over a cemetery.

The Montmartre cemetery, just west of its namesake hill, holds graves bearing such names as Stendhal, Zola and Berlioz. Once a quarry, the site became a mass grave during the Revolution, and as cemeteries in Paris had already reached saturation, its position as a burial place was soon formalised. In 1825, it was massively expanded to become one of several large cemeteries outside the city walls.

In 1860, during Haussmann’s famous renovation of the city, it was subsumed into Paris in the annexation that created today’s boundaries. Haussmann’s far-reaching work included introducing new roads like the rue Caulaincourt, a sort of bypass of the Montmartre hill. To complete this new street, a viaduct would have to be built across the cemetery, on piers which would displace existing graves. Not surprisingly, this was unpopular with impacted families – some of whom were reportedly worried it would stop souls from reaching heaven – and the children of interred admiral Charles Baudin took their complaints to the Senate, which in May 1861 voted 50-38 to cancel the project.

Despite this setback, the bridge was reconsidered and approved in 1867, and finally built in 1888, standing on six cast-iron Doric columns.

9: Pont Saint-Ange

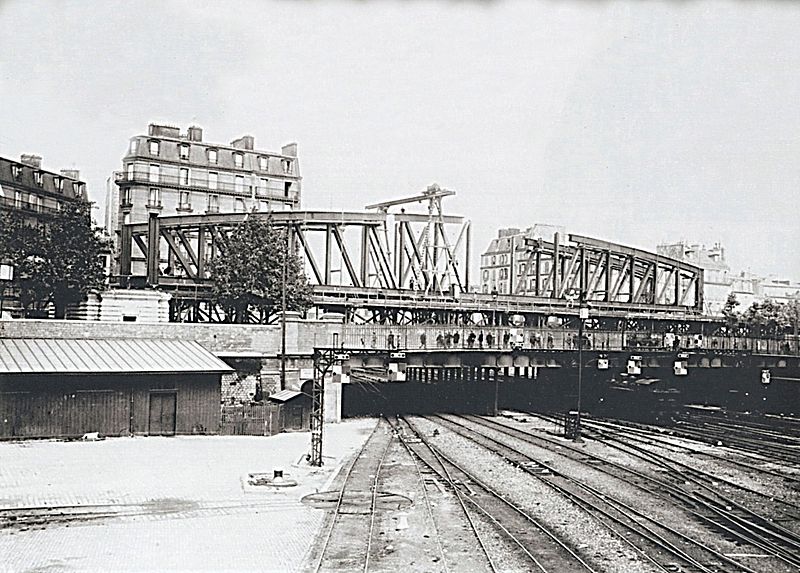

The geography of the eastern half of Paris’s 18th arrondissement is largely defined by two heavy rail lines – those leading to the Gare de l’Est, and those leading to Europe’s busiest railway station, the Gare du Nord. The district is bounded on its southern side by the Boulevard de la Chapelle, and when this road meets the railway it offers one of Paris’s more interesting bridges: the Pont Saint-Ange.

The Boulevard de la Chapelle dates back to the Wall of the Farmers-General, which sat at the edge of the city until its enlargement in 1860; the boulevard ran on the outside of the wall. In 1846, the first Gare du Nord was erected, at the completion of a railway to Lille and the Belgian border. This railway had only two tracks, so a small masonry bridge was sufficient to carry the road over the trains.

The bridge would undergo a series of modifications as the Gare du Nord expanded. In 1860, the destruction of the wall allowed the boulevard to be widened, and the stone bridge was replaced with a metal structure. But the biggest change, and indeed the crowning glory of the Pont Saint-Ange, came in 1903.

In 1896, the municipal council of Paris accepted Fulgence Bienvenüe’s project for a new metro network, which was then largely completed by the outbreak of the First World War. For reasons of speed and cost, most of the lines built during this time run in cut-and-cover tunnels under the city’s streets. Line 2, however, needed to cross both sets of rail lines as well as the Canal Saint-Martin. Tunnelling under these would have required complex, expensive work to dig beneath the water table, so a decision was made to erect a steel viaduct between the carriageways of the boulevard.

The entire viaduct is a wonder of early-20th century engineering, but on the Pont Saint-Ange it’s at its most impressive, crossing the entire bridge in just two 75 metre spans, three times the length of the spans elsewhere on the viaduct. The increased length means the trusses are higher here, making the bridge an impressive sight to behold. Unfortunately, there aren’t many public places from which to behold it, as the railway is lined with buildings. The best vantage points are offered by the next bridge along (the rue de Jessaint) and the platforms of the Gare du Nord.

If it can be seen from the platforms of the Gare du Nord, then it can also offer a view over those platforms, and that’s the main reason that the Pont Saint-Ange has made this list. Observers on the bridge deck can look down onto the platforms of the Gare du Nord and watch the arrival and departure of local, national and international trains. Indeed, in normal times, dozens of high-speed trains depart the station for London, Brussels, Amsterdam and Cologne, not to mention a vast number of national and suburban services.

From its humble beginnings as a small stone road bridge crossing two railway tracks, the Pont Saint-Ange has become an imposing metallic structure carrying both a road and a railway over 27 tracks.

8: Pont La Fayette

The next bridge on the list allows similar views over the Gare de l’Est, where, like on the Pont Saint-Ange, observers can see local, national and international trains, including some of the fastest trains in the world, which run at speeds of up to 320 km/h on the LGV Est towards Strasbourg and southern Germany. The luxury Venice Simplon-Orient-Express also arrives here from Calais (bringing passengers from London) and departs towards Venice and Verona.

In June 1849 – three years after the opening of the Gare du Nord – the first passengers boarded trains at the Gare de l’Est. Like the Gare du Nord, this first iteration was a tiny shadow of the station it is now; the railway had only two tracks, which went as far as Meaux, 41 km away. On its way to the station, the railway was crossed by a number of roads, the last of which was the rue La Fayette. This street, an important axis, crosses the tracks at an oblique angle on its way from the Opéra district towards La Villette.

Like the Pont Saint-Ange, the Pont La Fayette must have been through several iterations; but not a lot is written about the first bridges. The latest version was completed in 1928, after an explosion in traffic in the first part of the 20th century. At the time of its construction, the Gare de l’Est was undergoing a massive expansion, taking the number of platforms from 16 to 30.

Like the other bridges on this list so far, the Pont La Fayette is a truss bridge, but this time it’s made of reinforced concrete, which by the 1920s had replaced steel as the most popular engineering material of the day. According to a 1927 report by the Ministry of Public Works, this bridge was the first of its type.

7: Pont du Cours de Vincennes

No discussion of Parisian bridges would be complete without a nod to the Petite Ceinture. This railway encircling Paris, now mostly disused, carried regular passenger services as well as freight until the 1930s. When the tracks were first laid between 1851 and 1869, much of the line was on the level, intersecting with the city’s roads at level crossings. But in time for the 1889 Exposition Universelle – the world’s fair at which the Eiffel Tower would make its debut – work was carried out to change this. In parts of the city, the railway was lowered into cuttings and bridges were built to carry roads over it. Elsewhere, the track was raised to run on embankments and viaducts, and this is what gave us the line’s best structures.

In the 19th arrondissement, near the canals, the line runs along a stone viaduct – the Viaduc de l’Argonne. The narrow rue Dampierre passes under it at this point, looking for all the world like a quaint provincial lane and not a street in a major capital. You can see this bridge on Google Street View, or here along with a few others from the neighbourhood.

After plunging into a tunnel under the Buttes Chaumont hill, then running in a cutting, the Petite Ceinture once again rises above street level in the 20th and 12th arrondissements. Most of the bridges it crosses here are either masonry arches or longer metal affairs. The most impressive of all of these is the Pont du Cours de Vincennes, which crosses the Cours de Vincennes. This road, which separates the 20th and 12th arrondissements in the east of the city, is more than 80 metres wide here, with space for eight lanes of traffic, two tram stations (each with two tracks and two platforms), a parking lane, and pavements.

The metal bridge rests on 24 cast-iron columns, arranged in six rows spaced evenly along its length. The two central rows have their feet in the roadway, separating the inside lanes from the rest of the road. In an elegant touch of history, the tram stations standing symmetrically either side of the road serve as the terminal stations of lines 3a and 3b, which together form a partial loop around Paris along the Boulevards des Maréchaux. These tramways serve a function similar to that once fulfilled by the railway.

6: Passerelle Marcelle-Henry

The quartier of Batignolles, in the northwestern 17th arrondissement, has changed beyond recognition in recent years. As recently as 2005, the northern part of this neighbourhood was an industrial wasteland, with 60 hectares of rail freight yards. Then, as part of Paris’s bid for the 2012 Olympics, the area was earmarked for redevelopment.

Although the schedule was relaxed, work still went ahead despite the Games being awarded to London. In 2007, the Parc Clichy-Batignolles — Martin-Luther-King opened; this park is still being expanded, and has become the focal point for a truly modern, ecological development, with 3400 homes, 30 000 m² of commercial space and 140 000 m² of offices, as well as public facilities and a major new courthouse.

The new neighbourhood is sliced by the rail lines into the Gare Saint-Lazare, with the park and the bulk of the new development on the northeastern side, but also a number of new buildings along the southwestern side. Prior to the recent work, these were only connected by the Pont Cardinet at one end and an underpass of the Boulevards des Maréchaux at the other, making access between the two difficult. As a result, two new bridges have been constructed: a road bridge carrying the rue Mère-Teresa, opened in 2018, and a footbridge opened in 2019: the Passerelle Marcelle-Henry.

Designed by Marc Mimram, the award-winning engineer behind the Passerelle Léopold-Sédar-Senghor (my fifth-favourite bridge over the Seine), this new steel footbridge undulates for 120 metres across 23 rail tracks. Its symmetry is rotational rather than reflective: as you cross the bridge, the fences rise up first on your left, and then on your right. The curvature of the ensemble invokes the feeling of waves, even though this bridge crosses a river of rails, rather than of water.

Where the fences rise and curve over the path, seating is provided. Unfortunately, however, the view over the tracks is impeded by the nature of these fences, constructed of a tight metal mesh which lets light through but doesn’t allow a clear perspective. This appears to have been a deliberate design choice, but I personally would have preferred a more unimpeded view. All the same, it’s a bridge that’s both a pleasure to cross and a pleasure to look at from elsewhere. The bridge won Mimram an Eiffel Trophy, an architecture award for steel constructions.

Construction of the bridge was not without problems and inevitable delays. For example, the paving stones on the southwestern end had to be reordered after the initial measurements were found to be too imprecise. And while the steps at one end include ramps for cyclists to walk their bikes onto the bridge, these ramps appear to be too steep for wheelchairs. Paris is often a rather inaccessible city, but this is easier to understand in ancient alleyways and hundred-year-old metro stations than brand new constructions. But, all these criticisms aside, the passerelle is a beautiful new addition to Paris’s infrastructure scene, and deserves its place on this list.

To be continued…

Don’t miss the rest of the countdown, and, if you want more articles about Paris’s infrastructure, sign up below to be notified of new posts by email.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris