A short walk from my house lies the Place de la République, famous as an assembly point for demonstrations. This plaza, at the border between three arrondissements, is the meeting point of a number of streets. Among them are three with very similar names: the rue du Temple, the boulevard du Temple and the rue du Faubourg-du-Temple. A little up the road the same thing happens: the rue Saint-Martin, the boulevard Saint-Martin and the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin all meet at the same point. In several other places, the same thing happens. What’s behind this naming?

Where the latter three streets meet stands a triumphal arch, called the Porte Saint-Martin. 200 metres to the west stands a similar arch, called the Porte Saint-Denis. What are these doing here? Why are they referred to as “portes” (“gates”)?

Where does the place d’Italie get its name? The rue des Fossés-Saint-Bernard? Why is every exit of the boulevard périphérique referred to as a “porte”?

The common factor in all of these cases is city walls. Over the centuries, Paris has been protected by various fortifications; as the city expanded, new walls were built and old ones demolished or incorporated into the architecture. Each of them left its mark.

The first walls

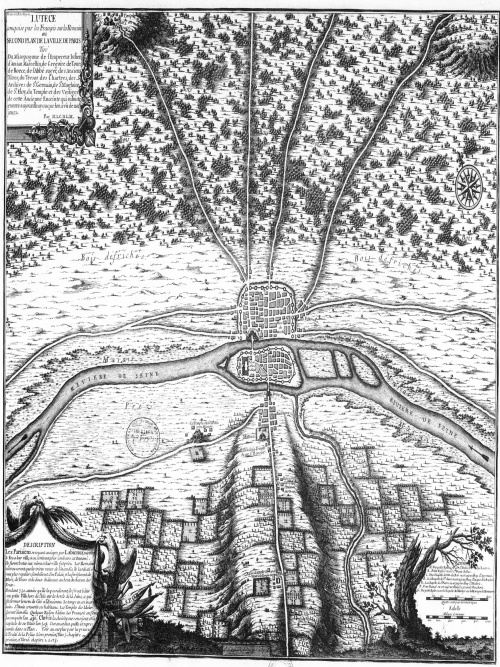

While it’s possible the Gauls had a settlement on the Île de la Cité, recent discoveries suggest Paris’s pre-Roman predecessor was actually based on another island, further west. The first substantial settlement at the site of modern Paris for which we have evidence is Lutetia, settled by the Romans after conquering the region in 52 BC. This was mostly based on the left bank of the Seine, but during the Pax Romana it seems there was no need for stone defences here. When Rome’s power began to dwindle and the first Barbarian invasions began, the population decamped to the Île de la Cité and built themselves a wall there, using stones from the old Arènes de Lutèce.

It’s not known exactly when these walls were destroyed, but during the Early Middle Ages settlements began to develop on the right bank, until then an uninhabitable marshland. It seems that after Viking invasions in the ninth century the Parisians built their first wall on this side of the river. But the first wall for which we have detailed information is the Philip Augustus wall, constructed between 1190 and 1215.

The Philip Augustus wall

This wall is named after Philip II, the king at the time, who successfully developed France into a stable western European power and needed the defences for his wars with the English.

South of the river, the wall’s delineation is still represented in the street layout. Some of the streets which follow it reflect this in their names: the rue des Fossés-Saint-Bernard and the rue des Fossés-Saint-Jacques are named after the defensive ditches (fossés) they replaced. The rue de Buci in Saint-Germain-des-Prés is so-named because it led to the Porte de Buci. The rue de Seine is named because the moat here led directly to the river.

On the right bank, the street pattern doesn’t reflect the wall, but various traces can still be found today. Most of these remaining sections have been incorporated into buildings.

This wall is a favourite of Oliver Gee of The Earful Tower podcast, who used to play basketball next to this wall and has since produced two wonderful episodes about it. In June 2018 he traced the wall’s remnants on the right bank; in March 2021 he did the same thing on the left bank. The 2021 podcast was surprisingly thrilling, and really brought the wall to life. A few days later, Oliver published a roundup of the seven remaining towers, and how to find them.

The following centuries saw a recurring pattern:

- The area enclosed by the city walls densifies until it is entirely built over

- Development then spills outside the walls, along roads leading into the city gates, creating suburbs known as faubourgs

- Eventually, these faubourgs are significant enough to be included in a new wall

- Newly enclosed empty space is filled in, returning to step 1

The walls of Charles V and Louis XIII and the Grands Boulevards

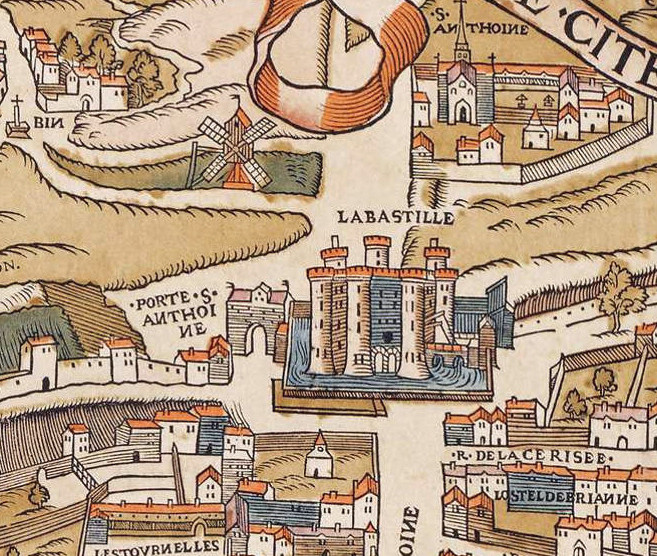

By the time of Charles V, in the latter half of the 14th century, the city had expanded greatly, with many new faubourgs. With the backdrop of the Hundred Years War, Charles V built a new set of fortifications encompassing some of these suburbs. South of the river the Philip Augustus wall was kept, but to the north the city expanded to encompass all of the present-day 3rd and 4th arrondissements. In the east, the Bastille was built to defend the king’s residence, the Hôtel Saint-Pol.

Two centuries later, the Wars of Religion necessitated an upgrade of Paris’s defences, especially in the west, where the Tuileries Palace was outside Charles V’s wall and new faubourgs had sprung up. As well as improving the defences in the east, a new structure was built in the west to encompass these new developments. This wall was finally completed in the 1630s, during the reign of Louis XIII, when the now obsolete section of the Charles V wall (between the river and the Porte Saint-Denis) was destroyed and built over. The present-day rue d’Aboukir and rue de Cléry follow much of the path of this section.

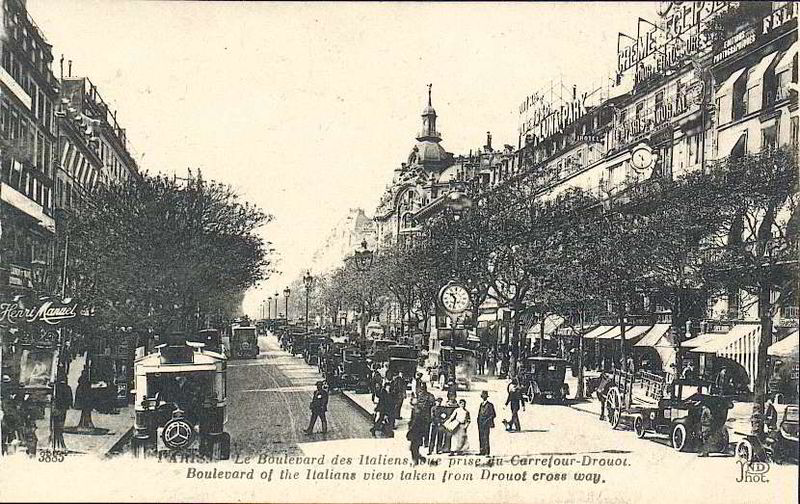

In 1670, in the wake of military successes in the Netherlands and to demonstrate to the population that they were safe from attack, Louis XIV ordered the walls be replaced with wide, tree-lined streets, whose military origins are reflected in their names: the word “boulevard”, cognate with “bulwark”, originally meant “rampart”. Unlike the narrow lanes of the rest of the city, these boulevards were wide and grand, and they proved popular. It’s thanks to these streets that the word boulevard came into the English language. In the renovations of Baron Haussmann, the concept was taken further, so that many of today’s “boulevards” have no defensive history at all. Those that date from Louis XIV are today known as the Grands Boulevards.

Many of the boulevards created by Louis XIV carry the names of gates that existed before. The streets leading up to these gates from either side share those names, with the addition of the word “faubourg” in the case of streets on the outside of the former walls. Two of the entrance gates of the Charles V wall, the Portes Saint-Martin and Saint-Denis, were replaced with triumphal arches celebrating the king’s victories. These still stand today on the southern boundary of the 10th arrondissement, either side of Strasbourg-Saint-Denis metro station.

The Wall of the Farmers-General

With the demolition of the old walls, Paris once again expanded and gobbled up its nearest suburbs. Mirroring the Grands Boulevards of the right bank, the boulevards du Midi were constructed in the south. But more populous neighbourhoods developed in the east.

Paris’s next wall was built not for military purposes, but to collect revenue for the monarchy of Louis XVI, struggling financially after costly foreign wars. At the wall, constructed between 1784 and 1789, goods entering the city were taxed by an organisation known as the Ferme Générale. These “octroi” taxes made the wall deeply unpopular at a time when the king was already viewed in a bad light. Indeed, 1789 marked the beginning of the French Revolution in which Louis was guillotined.

However, the Revolution didn’t mark the end of the wall or the octroi. To bypass this tax, guinguettes – a kind of bar – developed outside the wall. The town of Bercy attracted huge wine storehouses, which would furnish the city with wine during the siege of 1870-71 and last until the middle of the 20th century.

A few buildings remain from this wall, including a rotunda in the Parc Monceau and another overlooking the Bassin de La Villette. Several modern squares are at the site of barrières, or checkpoints, including:

- the Place de la Nation, where the towers and pavilions of the Barrière du Trône still stand

- the Place Denfert-Rochereau, formerly the Barrière d’Enfer (Hell’s Gate), whose pavilions are also still in place, and still in public hands. The name of this square is a pun – d’Enfer and Denfert are homophones. Pierre-Philippe Denfert-Rochereau successfully defended the territory of Belfort in the Franco-Prussian War, and the square was named in his honour.

- the Place d’Italie, formerly the Barrière d’Italie on the road to Italy. One of the pavilions was originally used as the town hall of the 13th arrondissement, but was later demolished.

The Thiers wall

Constructed in the early 1840s, the Thiers wall (named for Adolphe Thiers, Prime Minister at the time) was built at some distance from the edge of Paris, passing through some suburbs (such as Bercy and Montmartre) and completely enclosing others (e.g. Belleville and La Villette). This wall was built under the conviction of Louis-Philippe that the defence of Paris was key to defending the nation of France. The king was keen to avoid a repeat of the 1814 Battle of Paris, which had triggered the surrender of France and the exile of Napoleon. The wall was supplied with troops and armaments from the inside by a road and, later, a railway: the Petite Ceinture.

In 1860, Paris expanded its borders up to this new wall. The wall of the Farmers-General was now no longer necessary, and was destroyed quickly and without public opposition. That wall, like the one before it, was converted into a series of boulevards, now closely followed by lines 2 and 6 of the metro. The octroi taxes continued, now over an expanded territory, until their abolition in 1943.

With the expansion of the city limits, another series of boulevards was created, using the military road on the inside of the wall. These are known as the “Boulevards des Maréchaux”, as they are named after marshals of the First Empire. Outside the wall, meanwhile, was a 250 m-wide band of further defences, on which building was prohibited. From the end of the 19th century this attracted slums and became known as “La Zone”.

By the 1920s, military technology had rendered this type of defence obsolete and the wall was demolished. The “zone” beyond began to be built on, with social housing, parks and other developments. In 1958, the boulevard périphérique, a busy urban highway, was built in this zone, creating a new physical and psychological barrier between the city and its neighbours. The current mayor, Anne Hidalgo, has expressed a desire to transform this road into an urban boulevard; together with extensions of the metro and the cooperation of the Métropole du Grand Paris, this might go some way to bridging the divide, still strong today, between Paris and its suburbs.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris