It’s customary at this time of year to think about the dead.

Schoolchildren across France are home from school at the moment to mark a holiday known as La Toussaint: All Saints’ Day. The school holiday lasts two weeks, but always includes 1 November, a public holiday traditionally marking the Christian feast day. In the Roman Catholic calendar, this is the second day of a three-day festival which also includes Halloween and All Souls’ Day. The latter is sometimes known as the Day of the Dead.

Many historians believe that the Christian tradition has its origins in the pagan Celtic festival of Samhain, celebrated by the Gaels in Ireland and Scotland. According to this theory, Irish monks, influential in the early Middle Ages, introduced it to the rest of Europe. It’s possible a similar holiday was observed by the Celts of ancient Gaul – some have connected it with the month of Samonios, the first month of the Gaulish calendar – but there is no concrete evidence of such a celebration in the territory of modern France.

Regardless, people in Paris have been thinking about the dead at this time of year for at least a thousand years. So let’s follow in their footsteps with a story about a great Parisian tourist attraction: the Morgue de Paris. Did I just say “tourist attraction”? About a mortuary? Read on…

The Morgue

Today, Châtelet is best known as a labyrinthine metro station at the heart of Paris, part of one of the world’s largest underground hubs. The station is named for the place du Châtelet, a public square and road junction on the right bank of the river, opposite the Île de la Cité. But the word “châtelet” denotes a small castle, and that’s what gave the square its name.

The Grand Châtelet originated in the 9th century as one of two wooden fortresses protecting the bridges between the island and the banks of the Seine. Around 1130, these wooden structures were replaced with stone; but at the end of that century, Philip Augustus’s wall rendered them obsolete.

Though no longer serving its original purpose, the Châtelet remained intact and began to be put to new uses, housing court rooms, a prison and – this was medieval Europe, after all – torture chambers. In the prison, jailers would inspect the faces of arriving captives, the better to recognise them if they tried to escape. The French verb for this process is “morguer”.

In the 14th century, part of the prison was given over to the storage of dead bodies. Corpses found in the river or on the street were placed here, visible for passersby to identify. Now, Parisians could “morguer” these bodies. The precursor to the Morgue de Paris was born.

The Châtelet served as a prison until the Revolution; the building was demolished in the following decades, with the last vestiges surviving until the 1850s. In the meantime, a new home was found for the city’s dead: the Morgue de Paris.

The tourist destination

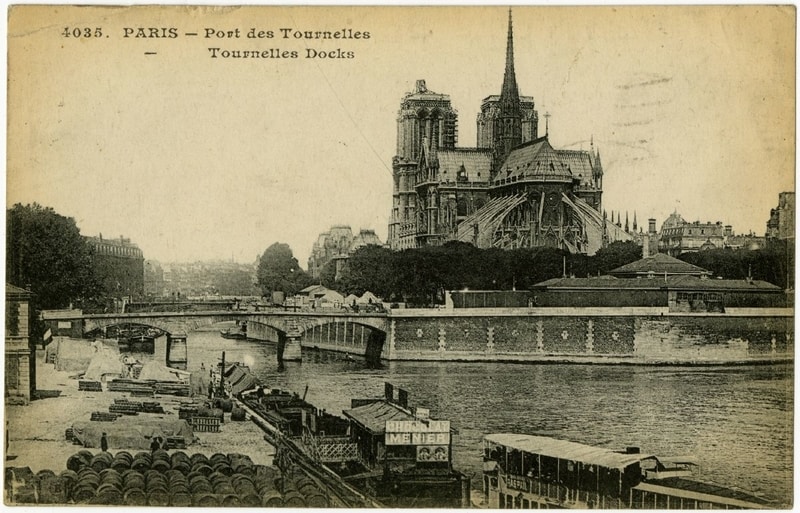

In 1804 – at the beginning of the reign of Napoleon I – the storage of Paris’s dead was moved to the quai du Marché Neuf on the Île de la Cité. Here, members of the public were invited to look through a window at a row of black marble tables, upon which were laid the unidentified corpses of people who had met their death in the city, often by drowning in the Seine. The logic was that displaying these bodies in public would allow them to be identified. But it soon became a morbid destination for an afternoon out. Unlike many Parisian entertainment venues, this one was free of charge.

In 1868, during the renovations of the city by Baron Haussmann for Napoleon III, the Morgue moved to a larger site, still on the island. The macabre spectacle flourished here, with 40 000 visitors per day, including tourists from far and wide. Tour guides included it as a must-see sight. English travellers were especially enamoured.

In one case, a four-year-old girl was found in the third arrondissement, dead but with no signs of injury except a bruise to the hand. Once this hit the local papers, the city went wild. During the customary three-day exposition of her body, 150 000 visitors passed through the Morgue’s doors, allowed in in batches of 50 to briefly ogle the diminutive cadaver. Fights broke out in the crowds as impatient spectators vied for position.

Sometimes, visitors would get more than merely a glimpse at a corpse. The police would bring suspects to the Morgue in the hope the sight of their victims’ bodies would trigger a confession. On occasion, this worked.

Today’s successor: the Institut médico-légal de Paris

In 1907, the prefect of police finally restricted access to the Morgue. Then, in 1913, work began on a new building in the 12th arrondissement. Delayed by world war, the newly christened Institut médico-légal (institute of forensic medicine) opened in 1923. It still operates at this site, standing by the river adjacent to the Viaduc d’Austerlitz.

The modern institute performs around 2000 autopsies each year, with another 1000 external examinations. Unidentified corpses are brought here for identification, along with the bodies of people who died in the street or under suspicious circumstances. After a long and sordid history, the IML today performs a vital public service. Meanwhile, the public have found other ways to satisfy their voyeuristic tendencies.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris