It won’t have escaped your notice that Americans are going to the polls today in a presidential election. Political predictions and analysis are outside the remit of this blog, but as the world’s eyes are on the United States today, let’s look at how that great country has influenced the toponymy and streetscape of Paris.

The storied Franco-American relationship dates back to the very origins of the USA. France supported the American Patriots in their Revolutionary War, and the subsequent French Revolution was largely triggered and inspired by this war. Relations were strengthened during the early Third Republic, when the two countries were among the world’s only major republics, and then in both world wars, where American financial and military support was vital to France’s liberation. Thereafter, France was one of the main beneficiaries of the Marshall Plan, and the two countries have since remained key allies as part of NATO. Throughout these two and a half centuries, the republic across the pond has left an indelible mark on the French capital.

Presidential places

A number of Parisian locations are named to honour POTUSes past. In chronological order1:

- The Rue Washington, a narrow street in the 8th arrondissement off the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, is named after the first US president.

- The Square Thomas-Jefferson, a park in the 16th arrondissement, is named after the third president, author of the Declaration of Independence and contributor to the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

- The Rue Lincoln, another street off the Champs-Élysées, honours the 16th president, remembered for the Emancipation Proclamation, Civil War victory, and his assassination.

- The Avenue du Président-Wilson, a grand, wide street in the 8th and 16th arrondissements, remembers the president who brought the US into the First World War.

- The Avenue Franklin-Delano-Roosevelt pays tribute to the president who brought the US into the Second World War. Once named after Italian king Victor Emmanuel III, it gained its current name just after Roosevelt’s death. This reflects the wartime renaming of several other Parisian streets. Located in the 8th arrondissement, it also gives its name to a metro station on the Champs-Élysées.

- The Avenue du Général-Eisenhower, also in the 8th, is more a homage to the general than the president, for his role in the liberation of France.

- The Avenue du Président-Kennedy, a major road by the Seine in the 16th, is named after assassinated president John Fitzgerald Kennedy, whose 1961 speech at the Hôtel de Ville had impressed the local council. The name also extends to an RER station.

All of these are clustered in the west of the city, specifically in the 8th and 16th arrondissements. Perhaps this is because of their relative proximity to the US embassy at the Place de la Concorde.

Other street names

The Square Thomas-Jefferson is itself located in the Place des États-Unis – the United States Square. Meanwhile, as the Avenue du Président-Kennedy continues eastward, it becomes the Avenue de New-York. Before 1945, this latter road was the Avenue de Tokio, but like the Avenue Franklin-Delano-Roosevelt, renamed because of fascist Italy’s allegiance to the Axis powers, its name was changed because of wartime opposition to Japan.

Another park in the 16th arrondissement honours a decisive American victory in the Revolutionary War – the Square de Yorktown.

Myriad other Americans are honoured in the street names of Paris. These include:

- politicians (e.g. Rue Benjamin-Franklin, Avenue Myron-Herrick, Place Harvey-Milk)

- military officers (Boulevard Pershing)

- philanthropists (Rue George-Eastman, Avenue David-Weill)

- philosophers (Place Hannah-Arendt)

- writers (Rue Ernest-Hemingway, Place Gertrude-Stein)

- musicians and dancers (Rue Ella-Fitzgerald, Place Louis-Armstrong, Rue George-Gershwin, Place Joséphine-Baker, Place Léonard-Bernstein, Allée Isidora-Duncan, Rue Martha-Graham).

The Founding Fathers, though celebrated for their work in building the American republic, are also criticised as slave owners. Similarly, President Woodrow Wilson is celebrated for bringing the US into the war, and for many of his domestic policies, but criticised on issues of race. It’s welcome, then, that civil rights activists are also recognised in Paris’s toponymy: the aforementioned Josephine Baker, but also Rosa Parks (with an RER station and associated parvis) and Martin Luther King (the Parc Clichy-Batignolles – Martin-Luther-King).

Statues

Of course, it’s not just the names of Paris’s streets that testify to this transatlantic relationship. It can also be witnessed in some of the city’s many statues.

The Statue of Liberty, a gift from France to the United States dedicated in 1886, has several echoes in Paris. Three years after its inauguration, a replica of the statue was unveiled on the Île aux Cygnes. This statue stands 11.5 metres tall, a quarter of the height of the original. Three other copies have been erected in Paris, each 2.86 metres in height. One, created for the 1900 Exposition Universelle, stands outside the Musée d’Orsay; another is set in the Jardin du Luxembourg; and a third guards the entrance to the Musée des Arts et Métiers. More recently, in 1989, a full-size replica of the statue’s golden flame was erected in the Place de l’Alma. After the events of 31 August 1997, this monument was coopted as a memorial to Diana, Princess of Wales.

The Square Thomas-Jefferson has four monuments: statues of former US ambassador Myron Herrick and pioneering American dentist Horace Wells; a monument to American volunteers in the French army in the First World War; and a statue of George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette. Washington has another statue not far from there, this time on horseback, looking towards the Trocadéro from the Place d’Iéna.

Frenchmen honoured for their service to the US

The victory of the Americans in their war of independence was aided significantly by French involvement. Two men in particular are hailed as heroes in the USA: the Marquis de Lafayette and François Joseph Paul de Grasse. Lafayette is remembered for his role in the battles of Brandywine and Rhode Island, and in particular the Americans’ decisive victory at the Siege of Yorktown. De Grasse, meanwhile, was an admiral whose role at the battle of the Chesapeake was also key to the Patriot victory at Yorktown.

A statue of Lafayette was erected in 1908 in the Cour Napoléon, where the Louvre pyramid now stands, funded by Americans to thank France for the Statue of Liberty. When the pyramid was built, the marquis’s statue was moved to the Cours la Reine in the 8th arrondissement. For his part, De Grasse is honoured with a bronze monument in the Trocadéro gardens, commissioned by an American philanthropist and erected in 1931.

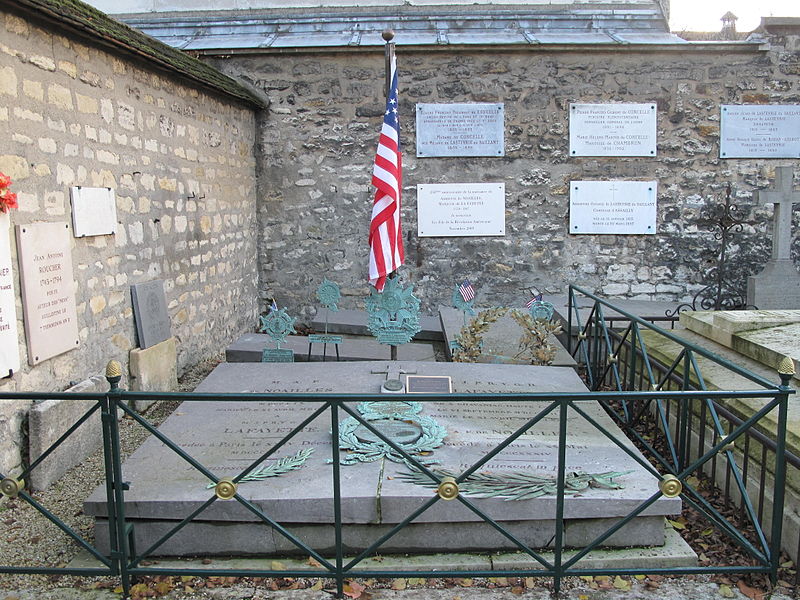

Both men are buried in Paris. Lafayette’s body lies in the Picpus cemetery in the 12th arrondissement, a private cemetery which began life as a mass grave for the victims of the Reign of Terror. The US flag flies permanently over the marquis’s grave. De Grasse is entombed in the church of Saint-Roch in the 1st arrondissement.

False friends

I’ll close with some “false friends”: places whose names falsely suggest a link to the US.

In the 14th and 15th arrondissements, near Montparnasse station, lie the Avenue du Maine and the Rue du Maine. These aren’t named after the US state, but the Château du Maine, an hôtel particulier that once stood in the area. Ultimately, both the château and the state are named after the former French province of Maine.

In the 19th arrondissement, in the extreme north east of the city, stands an administrative district known as the Quartier d’Amérique. This area is named after the quarries that once lay there: the Carrières d’Amérique. These are rumoured to have been where the stone for the White House was mined. In fact, the American mansion is built from stone quarried at Aquia Creek in Virginia; the Parisian quarries were already named after America a century before US independence.

Finally, a metro station on line 7 in the 13th arrondissement, a nearby street, and the administrative quartier in which both lie, bear the name Maison Blanche, sharing their name in French with the American presidential palace. However, this name derives from the village that once stood there, itself named after a white inn. Unlike the building whose occupant for the next four years is being decided today, this particular white house is now long gone.

-

I’m not sure whether or not this is an exhaustive list; these are all the American presidential toponyms I could identify, but there might be others. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris