It’s the end of the 19th century. The Belle Époque is at its zenith. A transport revolution is underway in the City of Light. In a few short years, a new underground railway network will transform the way Parisians get around. But over the past few decades, another vehicle has already established itself: the tram.

In 1900, five distinct varieties of tram were circulating in the Paris region: horse-drawn, steam-powered, compressed-air, cable-hauled, and electric. We’ve covered the first four earlier in this series. We’re going to spend a long time on the final one. In today’s instalment, we look at the arrival and rapid flourishing of the electric tram, in its many different forms.

The first movers

To begin, let’s rewind to 1875. In Paris, tramway development is just getting underway, with a handful of horse-drawn lines and one operating with steam. Louis Mékarski is working on a prototype compressed-air tram in the eastern suburbs. A cable tramway, the first of many globally, has been established in San Francisco. But today’s story starts in a seaside suburb of St Petersburg.

The Miller’s line ran in the town of Sestroretsk on the Gulf of Finland. There, Ukrainian engineer Fyodor Pirotsky tested electric traction. It didn’t last, but the experiment – the world’s first electric railway1 – demonstrated the potential difference2 electricity could make to modern transportation.

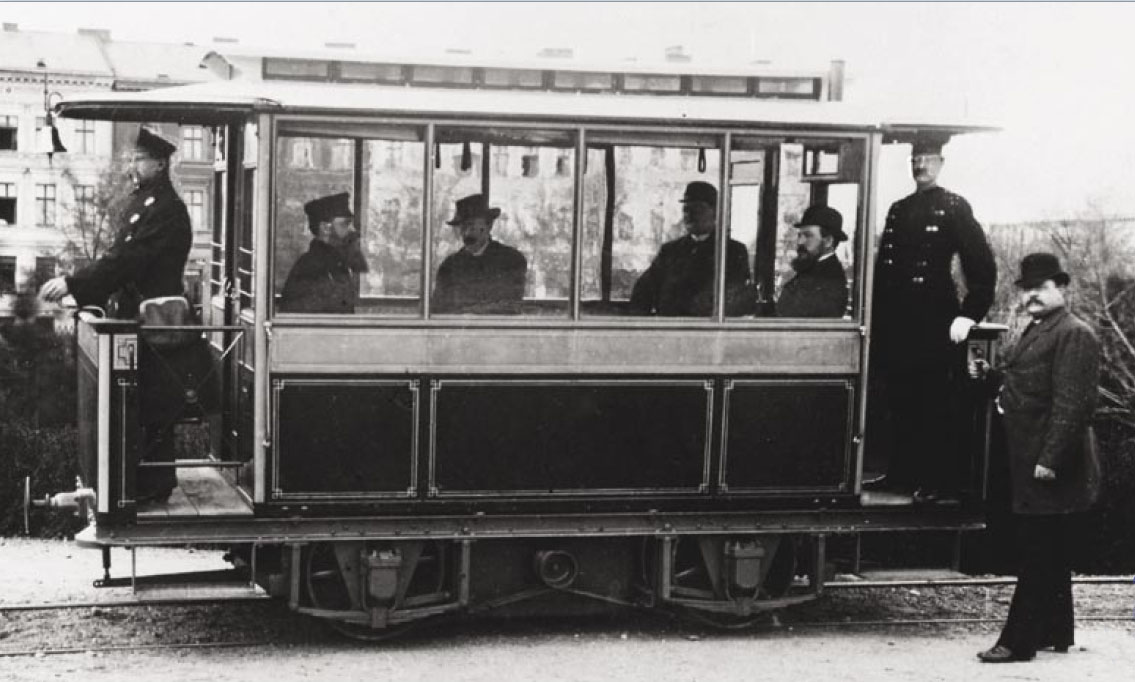

Carl von Siemens, working in St Petersburg for his brother Werner’s company Siemens & Halske, met with Pirotsky, and is thought to have learned a great deal from him. Four short years later, the company was demonstrating an electric tramway of its own, at the Industrial Exposition in Berlin. Two years after that, the world’s first permanent public electric railway, the Groß-Lichterfelde line, was operating outside the German capital. Siemens would remain in the business to the present day.

In the late summer of 1881 – just a few months after the opening of the Groß-Lichterfelde railway – Werner von Siemens presented his electric tramway in Paris, at the Place de la Concorde, as part of the International Exhibition of Electricity. But it would take seven more years for electric trams to enter genuine passenger service in the French capital.

Pirotsky and Siemens’s lines delivered electricity directly along the running rails. Aside from the obvious danger that this presents when coupled with street running (these early railways were segregated from the public street except at level crossings) it also came with serious performance disadvantages. A remedy for the latter problem was soon found in the form of the third rail. Pioneered in the mid-1880s on the island of Ireland, third rail electrification soon took off on segregated lines around the world, and survives to this day, especially on underground railways. But this technique remained hazardous on street-running tramways.

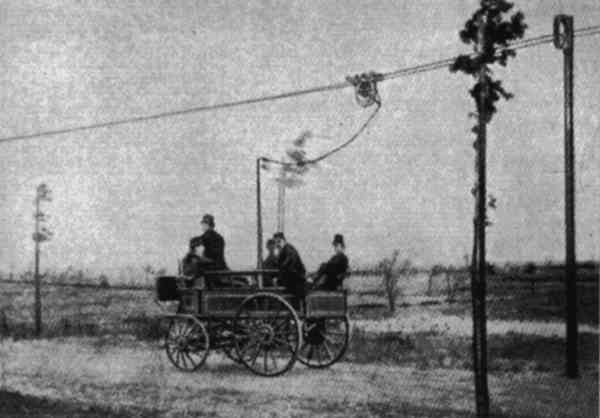

Fortunately, parallel to the development of the third rail, other techniques were being explored. In 1882, Werner von Siemens successfully delivered current to an omnibus using an overhead wire. His Elektromote, which ran outside Berlin between April and June of that year, functioned with a “Kontaktwagen” (literally, “contact car”): a wheeled unit which rolled along the top of the cables. In English, this would come to be called a “trolley”.

Siemens & Halske were quick to deploy this new technology to a tramway, on the outskirts of Vienna in 1883. Unlike the Miller’s and Groß-Lichterfelde lines, the Mödling-Hinterbrühl tramway was able to operate substantially on public streets.

Belgian engineer Charles Joseph van Depoele enhanced upon the trolley idea in 1885, demonstrating the first example of a trolley pole in Toronto. Enhanced by American inventor Frank J. Sprague, the trolley pole would become very popular on tramways. And while trams have since moved on, it persists to this day on trolleybuses.

Another method of delivering current without electrocuting unwary pedestrians was attempted, apparently independently, in 1885 in Blackpool, England, and in 1886 in Denver, Colorado. This method consisted of using an underground channel, or “conduit”. Trams carried a device known as a “plough” to pick up current from live wires under the roadway. But this technique wouldn’t last in either location. In Blackpool, wet sand from the beach clogged up the conduits and sea water caused short circuits. The system survived here until 1899. Denver gave up much sooner, abandoning it after only a year.

In 1887, the diverse array of electric trams was expanded once again, with trams powered by lead-acid batteries circulating in Wolverhampton, England. The following summer, this spread to Sydney, Australia.

Paris enters the scene

In Paris proper, overhead lines were banned from the start, ruling out trolley poles. The first electric trams here used batteries, or, to use the vocabulary of the time, “accumulators”. In September 1888, the Compagnie des Tramways Nord, which operated primarily in the northern suburbs, began employing these accumulator trams – adapted horsecars, with the batteries under the seats – on the 1 km stretch between the Place de l’Étoile and the Porte Maillot. The batteries were unloaded to recharge, this being a slow process.

The results were a qualified success: the performance benefits were considerable, but the batteries produced toxic acidic fumes, which filled the passenger seating area. The company (or rather, its successor the TPDS3) evidently found this an acceptable tradeoff, deploying the vehicles around the town of Saint-Denis, just outside the city walls, in April 1892. By 1898, the region’s 70 tram lines included 11 running with accumulators.

In the meantime, suburban lines began to embrace the overhead wire. The first was in 1895, when the Le Raincy-Montfermeil line – a route established in 1890 and hitherto running steam trams – switched to using trolley poles. In 1897, a new trolley line sprang up around the spa town of Enghien-les-Bains, way out to the north. The following year, the TPDS brought overhead lines right to the edge of Paris, in the neighbouring towns of Pantin and Le Pré-Saint-Gervais.

Of course, Paris’s first forays into electric traction didn’t signal the end of innovation elsewhere. There’s one more form of ground-level delivery that we haven’t discussed yet, because it didn’t spring up until the 1890s.

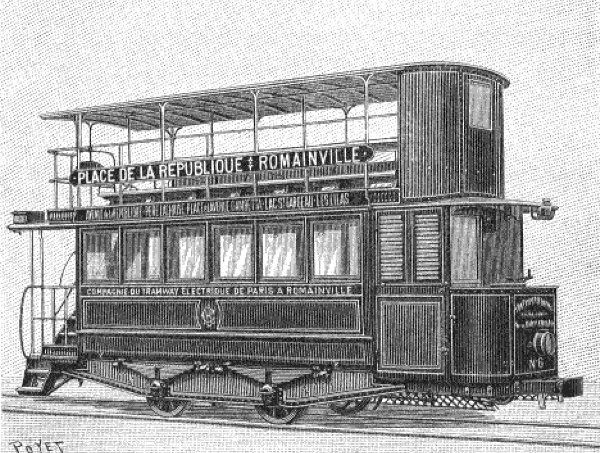

The Romainville tramway

For this part of our story, we must introduce Jean Claret, the man behind multiple tramways and other railways around France. In 1890, he brought overhead line electrification to the country in the form of the Clermont-Ferrand tramway. Then at the 1894 Universal Exposition in Lyon, he introduced a new method of current delivery, courtesy of engineer Olivier Vuilleumier: the stud contact system.

Under this system, a series of studs were placed in the roadway between the rails. A current collector under each tram, called a “skate”, would draw electricity as it passed over each stud, with the rails carrying the return current. In Claret and Vuilleumier’s system, the studs were spaced 2.5 metres apart and protruded 5 mm above the surface of the road. To avoid electrocuting passersby, each stud was only connected to the power supply when a tram was above it: the act of passing over one stud triggered the connection to the next.

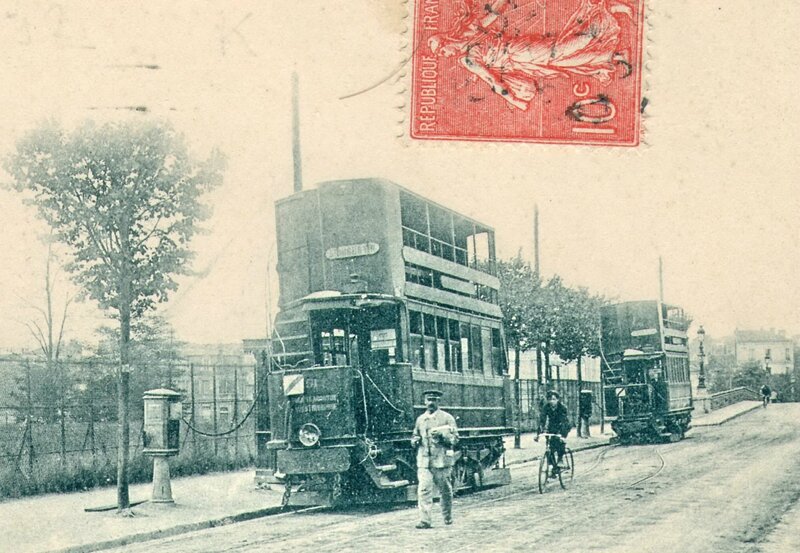

Claret brought the system to Paris in 1896, with a line between the Place de la République and the eastern suburb of Romainville. This wasn’t a flat route, but the trams proved up to the task of surmounting its hills. The line saw almost 3 million passengers in its first seven months.

Several other stud contact systems were invented around the same time. In 1898, the French city of Tours began using a system invented by Italian engineer Alfredo Diatto, which used magnets to ensure that each stud was only connected when a tram passed over it. The following year, Parisian Henri Dolter devised a similar system, later deployed in a number of English towns. But studs weren’t without their risks. Occasionally, the contacts would stick and a stud would remain electrified after a tram had moved on, presenting a mortal danger for humans and horses.

A network for the 20th century

We saw in this history’s earlier chapters how the Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) of 1889 spurred efforts to move beyond equine traction on the tramways of Paris. Another Exposition was planned for 1900, and this one would be a good deal larger: among other things, it would feature the second ever modern Olympic Games. This time, the horse was all but completely banished, with electricity the order of the day.

Several new companies sprang up around 1900, and a host of new lines were constructed. By this point, overhead wires had already established themselves as the most reliable – not to mention cheapest – way to power a tram. But as the city wouldn’t allow these within its walls, most of these new lines employed studs on Parisian turf and overhead wires elsewhere.

One company, the CGPT – which operated primarily in the southern suburbs – did manage to persuade the authorities to allow overhead wires in the city. In November 1898, they opened a line along the avenue Daumesnil, between the Place de la Bastille and the town of Charenton-le-Pont. To soften the impact of the apparently unsightly cables, they switched to a conduit where the line crossed important junctions. Each tram was thus fitted with both a trolley pole and a plough. The line was an instant success: trailers were soon added to its single-car vehicles to accommodate the demand.

Meanwhile, even as historic Parisian public transport operator the CGO began adopting Mékarski compressed-air trams, other lines were abandoning that technology in favour of electricity, using overhead wires where possible and various combinations of studs, conduits and batteries elsewhere.

In February 1900, a law was passed to reinforce the modernisation efforts already underway, as well as to provide a little order to the cacophony of different companies with their diverse vehicles and varied services. There would be no new horsecar lines; heating and lighting would be required on board, where first- and second-class seats would be provided in a 1:2 ratio; speed limits of between 16 and 20 km/h were imposed; and the existing near-total ban on trolley wires in the city proper was upheld.

Onward

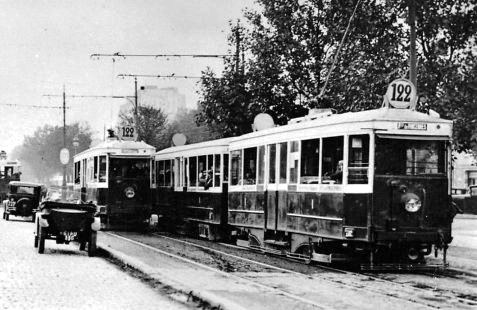

In the first decade of the 20th century, tram ridership rocketed. In 1909, a single line saw 17.5 million trips. But chaos still reigned: multiple competing operators ran often similar routes, leading to a confusing passenger offering and poor financial results for most of the players. Horsecars still shared the streets with the most modern of electric trams. And the blanket ban on overhead wires was a thorn in the side of operators, including in locations where the aesthetic argument was ill-justified. Further efforts would be required to iron out these issues. We’ll see the authorities’ response in part 6.

The Île-de-France tramway network was entering a veritable golden age. But its demise was perhaps already written in the stars. The metro had opened in 1900 and was developing at breakneck speed. The first motorbuses were circulating by 1906. And mass production of automobiles would soon transform the city’s streets: Ford France was established in 1911.

Part 6 will cover this golden age, defined by consolidation and further modernisation. After that, we will trace the tragic tale of the tramway’s departure from the region in the 1930s. But that will be far from the end of the story.

-

The first electric locomotive – powered by a battery – was built as far back as 1837 by Scottish chemist Robert Davidson. But the Miller’s Line appears to be the first electrified railway, using an external as opposed to on-board power source. ↩

-

See what I did there? ↩

-

Both Tramways Nord and Tramways Sud, the principal tram operators in the periphery of Paris, went into bankruptcy in the 1880s. They were replaced in 1890 by the Tramways de Paris et du Département de la Seine (TPDS) and Compagnie Générale Parisienne de Tramways (CGPT) respectively. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris