Since there has been only one news story recently, I thought I’d lean into it. Without further ado, here are seven British royals who give their names to things in Paris.

Mary, Queen of Scots: la rue Marie-Stuart

Perhaps this one is cheating, since Mary Stuart was a queen consort of France. But she did also rule over a part of the UK, and this story is such fun that I can’t be blamed for including it. I’ve actually told it on Fabric of Paris before, so please allow me to self-cite (with a content warning for coarse sexual slang):

The names of some of Paris’s most ancient streets continue to bear witness to their history as red light districts. The rue du Petit-Musc in the 4th arrondissement is an example. Historians attribute its name to a corruption of “Put-y-Musse”, meaning something like “where the whore hides”. Other examples have since changed name: the rue Gratte-Cul (“arse scratcher”) was renamed in 1881 to the rue Dussoubs, after a revolutionary killed nearby.

Intersecting with the rue Gratte-Cul stood the rue Tire-Vit (“screw cock” or “knob shagger”), which was also known euphemistically as Tire-Boudin (“pull sausage”). Legend has it that it received this new, less offensive name when the young king Francis II was out walking with his consort, Mary Stuart (usually known in English as Mary, Queen of Scots); she asked him the name of the street and he didn’t want to embarrass her with the vulgar appellation. This story is pure fiction – the name Tire-Boudin predates this couple by almost a century and a half – but it gained widespread popularity, and in 1809 the decision was made to rename the street the rue Marie-Stuart.

Victoria: l’avenue Victoria

Two Australian states. Two Canadian provincial capitals. The largest lake in Africa. A London rail terminal and Tube line. An era synonymous with the industrial revolution, the pax Britannica, the stiff upper lip. Britain’s second-longest-reigning monarch’s name crops up around the world. Including in Paris.

In 1851, at the suggestion of Victoria’s first cousin Albert – who also happened to be her husband – London hosted a grand international exposition of industry and manufactured goods. Inspired by a series of smaller-scale industry showcases in Paris, this Great Exhibition became the first of a new era of world’s fairs.

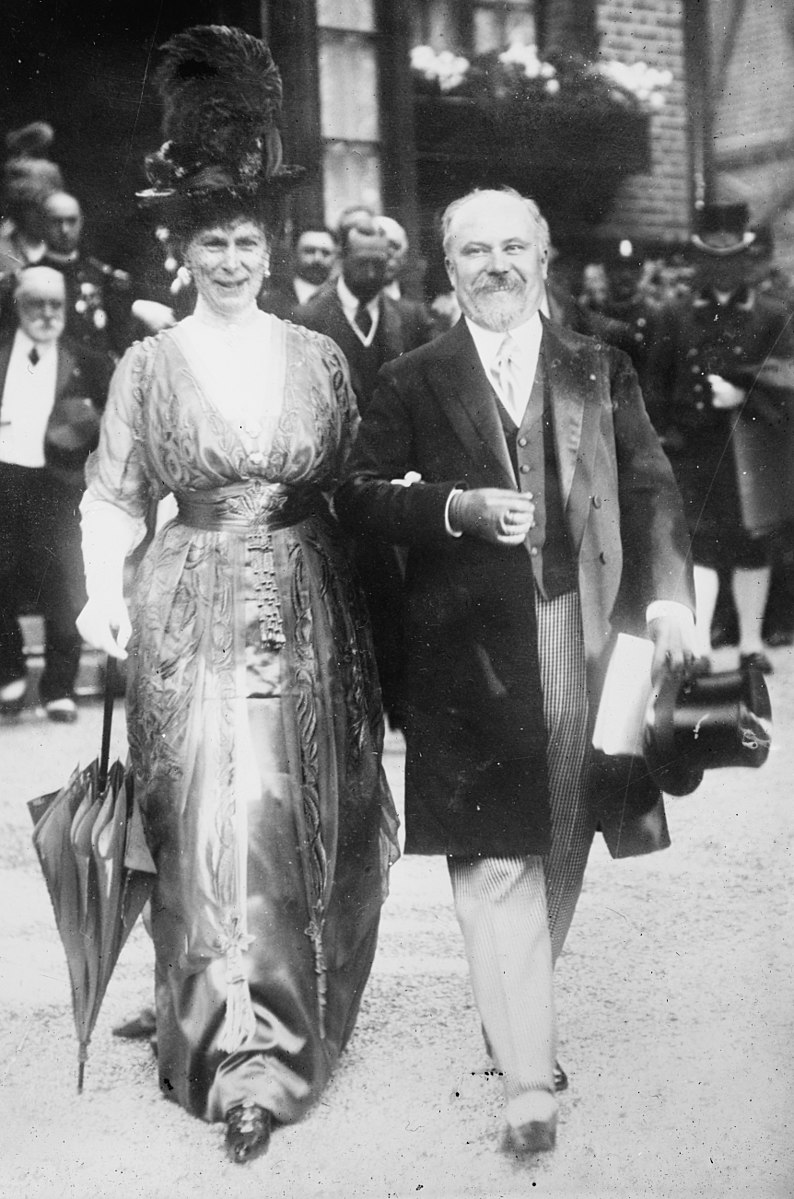

President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte looked on with envy as the world’s attention was drawn to London. “When I’m emperor”, we can imagine him saying to himself, “I’ll organise an even bigger exhibition in the true centre of the world.” A coup d’état and a royal coronation later, Emperor Napoleon III was decreeing a “universal exposition” by the Champs-Elysées. Naturally, Victoria and Albert would be invited.

It was only natural for the royals to meet, especially as French and British soldiers were fighting side by side in Crimea. Napoleon visited his counterpart in Windsor in April 1855. And in August, the British royal family returned the visit. Staying a little over a week, Victoria didn’t just visit the Exposition. She also found time to see the tomb of Napoleon I, in which the late emperor presumably rolled as God Save the Queen was played in her honour. But it was thanks to a visit to the Hôtel de Ville on 23 August that the City decided to name a street after her: the Avenue Victoria.

Decreed the previous year, the boulevard de l’Hôtel de Ville was one of many such boulevards and avenues created during the Second Empire. They were considered prettier than narrow alleys, but, more to the point for a newly proclaimed monarch, they’re also harder to barricade and easier to march an army down. It took on its new name in October 1855.

Edward VII: la rue Édouard-VII

By 1901, when Victoria left the throne to her son Albert Edward, France’s Third Republic was in its fourth decade. You would think Paris would have no room for a king. Yet it seems Edward found his place here. As Prince of Wales, Edward had developed friendships across Europe, and in France in particular. In 1881, he met with senior French politician Léon Gambetta to discuss a possible alliance, which would ultimately come to fruition during his reign with the 1904 signing of the Entente Cordiale. This alliance did nothing to improve Edward’s relationship with his nephew, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany; but by this point there was already little love lost between the two monarchs.

Edward died in 1910. The same year, plans were drawn for the rue Édouard-VII, a private street and building development in the 9th arrondissement. Spearheaded by French entrepreneur Arthur Millon, who had made his fortune in hotels and restaurants – including the swanky Café de la Paix, not far away on the Place de l’Opéra – it featured shops, restaurants, offices, a hotel and a cinema. In 1916, that cinema became the Theâtre Édouard VII, a theatre which has shown English-language plays in the past, and where English-speaking visitors today can enjoy subtitled productions. Revitalised in the 1990s, the now-pedestrian street sits in the heart of a major business and commercial district.

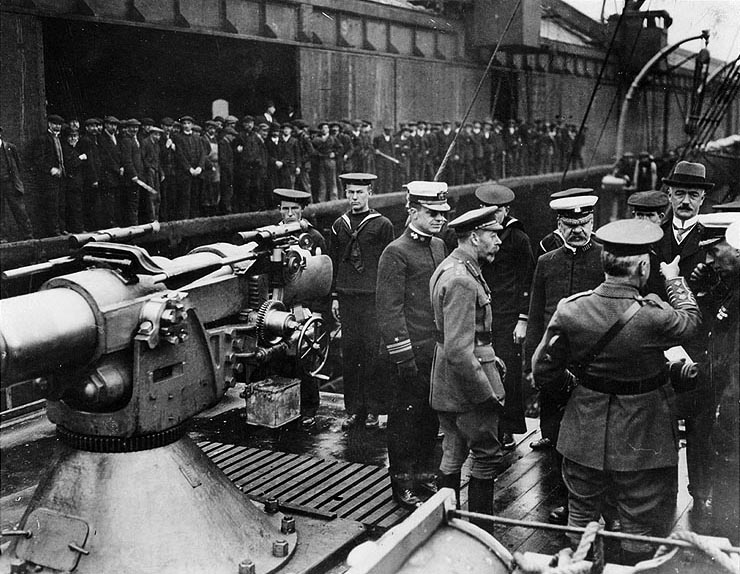

George V: l’avenue George-V

Four years after Edward’s son George took the throne, Europe was at war. In this context, George took his role as a figurehead seriously. His visits to troops, factories and hospitals boosted morale; his own sons enlisted in the armed forces; and he accepted a degree of rationing in the royal household.

Victoria’s marriage to Albert, a German, had given the royal house the distinctly German name of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Moreover, many members of the royal family bore German titles. Concerned about the imagery of this against the backdrop of anti-German wartime propaganda, George renamed the royal house Windsor, and granted new English titles to members of the family in exchange for them renouncing their German ones. British members of the German Battenberg family anglicised their name to Mountbatten, which is what gives us the modern royal surname.

On 14 July 1918, Paris gave George’s name to a prestigious avenue in the 8th arrondissement, connecting the Champs-Élysées to the place de l’Alma (which will make an appearance later in this article). The same month, the avenue du Président-Wilson had taken its modern name, after the president who had brought the United States into the war. That avenue runs west from the place de l’Alma.

The avenue George-V is today a high-end shopping street. It forms one side of the so-called Golden Triangle of expensive apartments, luxury shops and exclusive hotels. An eponymous hotel was opened on the avenue in 1928; today it’s a Four Seasons. Where the avenue meets the Champs-Élysées, a metro station on line 1 also bears the king’s name; on 19 September 2022, for one day only, this station was renamed in honour of Elizabeth II.

Edward VIII: la Villa Windsor

George V passed away on 20 January 1936 at the age of 70. His firstborn son Edward was now king. But this reign soon became embroiled in a scandal leading to his abdication. Indeed, Edward wanted to marry Wallis Simpson, a divorcee whose first husband was still alive, and the Anglican church – of which, as king, he was head – disapproved. Of course, times had changed by 2005, when the crown prince married a divorced woman who is now queen consort.

Following his abdication, the newly styled Duke of Windsor married Simpson in a château in central France, before settling in Paris. Originally Edward planned to return to the UK, but his family made it clear he would be unwelcome. A Nazi sympathiser, he was sent to the Bahamas in 1940 to serve as governor, presumably to keep him out of the way during the war. Lucky Bahamians.

After the war, the duke and duchess returned to Paris, where from 1952 they moved into a mid-19th-century mansion in the Bois de Boulogne. This hôtel particulier belonged to the City of Paris, who rented it to them for a peppercorn rent. The French state gave them other advantages too, including an exemption from income tax.

After the duchess died in 1986, Egyptian tycoon Mohamed Al-Fayed signed a 50-year lease on the château, renovating it over the next three years and renaming it the Villa Windsor after its late residents.

Diana, Princess of Wales

The Villa Windsor and its owner bring us to our next story. In July 1997, Diana, the ex-wife of the then-Crown Prince, began dating Mohamed Al Fayed’s son, filmmaker Dodi. After a sojourn on Mohamed’s yacht in the Riviera, they took a private jet to Paris’s Le Bourget airport, where they arrived on 30 August. That day, they visited the villa for a brief tour, planning to return the next day for lunch. It’s rumoured this lunch would have been a celebratory occasion to mark their engagement, and that the Villa Windsor would have become the married couple’s residence. But it wasn’t to be. That night, en route from the Ritz (also owned by Mohamed) to Dodi’s apartment near the Champs-Élysées, their driver lost control in the tunnel under the Place de l’Alma.

Today, the princess is memorialised in the Place Diana, near the site of the crash. Once again, please allow me to quote from an earlier Fabric of Paris about how it got its name:

Before 1997, this square didn’t exist as such, but was considered a section of the larger place de l’Alma. A sculpture – a replica of the flame carried by the Statue of Liberty – was placed there in 1989, but the square itself wasn’t given a name until July 1997, when it was named after Greek singer Maria Callas. The following month, the Princess of Wales met a tragic death in the adjacent road tunnel, and the Flame of Liberty, originally intended as “a symbol of the Franco-American friendship”, became an impromptu monument to the people’s princess. The Council of Paris soon wanted to rename it in honour of Diana, but didn’t gain British approval, and the project was initially abandoned. However, signs with the name of Maria Callas were never erected. Finally, in 2019, the square received its new name.

Elizabeth II - le marché aux fleurs Reine-Elizabeth-II

Elizabeth II was born during the reign of her grandfather, George V. She was a young girl when her uncle, Edward VIII, abdicated; but it was in part thanks to this that she went on to reign even longer than her great-great-grandmother Victoria. During her 70 years on the throne, she watched as her firstborn son’s marriage collapsed and finally ended, and later found herself the subject of conspiracy theories surrounding the death of her erstwhile daughter-in-law Diana. In a sign of quite how much society had changed since her childhood, her son remarried with a divorcee, who, the day of her death, became queen consort.

During her reign, Elizabeth made five official visits to Paris, meeting presidents De Gaulle, Pompidou, Mitterrand, Chirac and, finally, Hollande. Her last visit was in 2014, to mark the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings. During this visit, she returned to a flower market she’d seen for the first time as princess, in 1948. For the occasion, the market, which occupies part of the Île de la Cité, was renamed in her honour. There has been a flower market on the island since the First Empire, but the covered market we know today dates to 1924: two year’s before Her Majesty’s birth.

Which British royal will be next to give their name to a part of Paris? Will there be a Place Charles-III? An Allée William-V? Or will Elizabeth II be the last member of her family to be recognised in this way?

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris