Let me tell you a secret: on my first visits to Paris, I didn’t much like it.

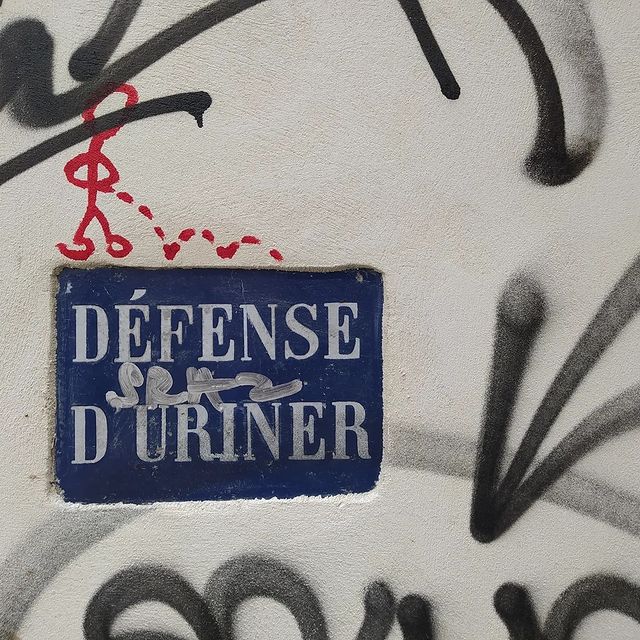

This might come as a shock to regular readers, as I hope my love for the city I now call home is visible in everything I write. But when I first visited, what stood out to me more than anything was the chaos, the dirt – and, in many places, the stench of human urine.

Of course it didn’t take me long to fall in love with the place (on my third visit, sweetened by a reunion with a beautiful girl I’ve since married). The organised chaos has become something I admire, and the dirt seems less important compared with the city’s architectural and cultural wealth. The sheer variety of experiences on offer keeps people coming again and again. And there is so much beauty here.

But it is dirty. The city’s street cleaners and refuse collectors do a sterling job, but are fighting a constant battle against the detritus of 2 million inhabitants and millions more daily visitors. Despite dozens of free public toilets, warning signs and nominal fines, nothing seems able to prevent public urination. And other forms of pollution persist.

As Anne Swardson points out in an excellent recent piece, it was ever thus. Tales of dirt and mess are probably as old as Paris itself. But if you spend any time on social media, you’ll be forgiven for thinking the phenomenon is much more recent. The Twitter hashtag #saccageParis (roughly, “trashing Paris”) is thrown around alongside criticisms of the current state of the capital, always with the implication that it’s the fault of the current inhabitant of the Hôtel de Ville.

The new hashtag, and the loose movement of opponents to mayor Anne Hidalgo coalescing around it, exploded into the news feeds of anyone associated with Paris earlier this year (just as Hidalgo’s rumoured presidential bid, made official last Sunday, was first making headlines). Besides decrying what Swardson describes as “a normal level of big-city inconvenience”, the hashtaggers also complain of ugly temporary infrastructure, short-term repairs, and new styles of street furniture which they see as departing from ancient Parisian traditions. But a lot of what I’ve seen falls into another category: motorists angry at policies like the closure of the rue de Rivoli, the removal of parking spaces, and the introduction of a 30 km/h speed limit across the city.

Cycle lanes are a particular peeve of many of the campaigners. The two favourite complaints are that they are largely unused, and that the increase in cyclist numbers is dangerous for pedestrians. Apart from the obvious dissonance between those two arguments, claims of “empty” cycle lanes typically rely on photographs taken at opportune moments of calm. As for safety, cyclists do all too frequently risk collisions with pedestrians when they go through red lights. That’s a real issue that needs addressing – but it won’t be solved by bringing back much more dangerous vehicles. Another disingenuous claim about cycle lanes is that they make it harder for emergency vehicles to get through. In fact, ambulances can use good-quality two-way cycle lanes to bypass traffic jams.

This is the dimension that some commentators have missed: a lot of the popular tweets with the hashtag are flagrantly dishonest. Unfinished roadworks are presented as complete1. Wild assumptions are made without evidence2. Photographic techniques are employed3 to mislead readers.

Some media reports on the issue – both in France and abroad – have inflated the size of the movement. Not only did Hidalgo win reelection last year a full twelve points clear of her nearest rival, but subsequent polls have shown that a clear majority of Parisians support her most controversial policies. As I reported last time, 59% agreed with expanding the 30 km/h speed limit. A survey last year of residents of Grand Paris – a wider area covering much of the suburbs – found that 62% supported making the pandemic’s temporary cycle lanes and restaurant terraces permanent, while 59% explicitly agreed with reducing the place of the private car in pursuit of a more ambitious cycling strategy.

tl;dr: don’t be fooled by the loud protestations of a minority of people angry that their model of city life is falling out of fashion. Progress is happening, and by and large, the people of Paris support it.

Truth be told, this wasn’t much fun to write. You can expect some more positive articles in the coming weeks, starting with the next instalment in our history of Parisian tramways. Sign up for email updates below if you don’t want to miss it.

-

This has happened a number of times, in particular when the council performs routine repaving work. Each time, the Mairie is accused of removing the traditional stone paving. But, weeks later, the stones reappear, exactly as planned. ↩

-

One popular English-language journalist shared a post about two of Paris’s traditional green lampposts seen sitting on top of a shipping container, adding the comment “urban furniture is simply put to the bin by the current municipality”. It’s not clear what happened here, but the hysterical tone seems entirely unjustified. Sometimes street furniture needs repairs or to be moved for roadworks. Perhaps these were victims of vandalism. In any case, the assumption that the local government is throwing away its historic street furniture is a serious reach. ↩

-

In one example, a poster took a few lovely shots of Rome in attempt to demonstrate that Paris is in a worse condition than that city (which is beautiful, but notoriously dirty). But the Roman photos were wide, upward shots taken in choice locations – quite unlike the pictures illustrating most #saccageParis tweets. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris