I’m a great believer in long walks. In particular, I like long urban walks. There’s no better to way to get to know a city than by walking its streets. I walk around Paris all the time, and even in places I’ve been wandering for years, I often spot things I’ve never noticed before. But I rarely get a chance for a proper hike – the kind of ramble that leaves your legs aching for the rest of the week.

To remedy this, I took a day off work on 5 October 2020 to walk the 20 km (12.5 miles) from the Hôtel de Ville in central Paris to the Château de Versailles, in the footsteps of the thousands of Parisian women who embarked on the same walk on 5 October 1789.

After a series of dramatic events in 1789, including the creation of the National Constituent Assembly, the storming of the Bastille and the hugely influential Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the events of 5 and 6 October represent the last major revolutionary episode of that year. Thousands of working-class women left their homes in Paris to descend on the king’s residence in Versailles, later to be joined by thousands of soldiers from the National Guard. The next day, they returned to Paris, with Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and their entourage in tow.

Today’s article takes a slightly different form to Fabric of Paris’s usual content. I’ll start by outlining the historical context, then allow you to virtually join me for the walk, taking a look at some of the key sights along the way. I’m indebted to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, which taught me a lot of what I know about the march (and indeed the entire Revolution).

Why did the women march?

Harvests in France had been bad all decade thanks to a series of adverse weather events. A poor yield in 1788 was compounded by a winter so cold it killed fruit trees and damaged stored grain. Unseasonably dry weather in September 1789 left streams empty and mills unable to function. By the end of the month, the scarcity of bread in Paris was fuelling conspiracy theories of an aristocratic plot to starve the city out.

The political context helped these rumours to flourish. The newly-formed National Constituent Assembly had given the king a suspensive veto, which looked to many as though the people were being sold out. Increased press freedom helped to stir up resentment among Parisians. And then Louis XVI did two things to poor oil onto the fire.

First, having promised to sign the Declaration of the Rights of Man, he wavered, asking for changes for the sake of German princes with land claims at the borders. Then in September, with a view to preventing a mob attack, King Louis called in a regiment from Flanders to swell the ranks of his defence force in Versailles. A banquet was thrown for the soldiers: evidently there was no shortage of food here. Reports of the evening in the radical press described soldiers throwing the revolutionary cockade to the floor, stamping on it and even urinating on it. With the king having personally attended the banquet, this looked like a deadly slight on the people and their revolution.

On 5 October 1789, all these ingredients finally boiled over. Early in the morning, bells were ringing across the city, rallying the people (mostly housewives) to the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville.

Some protesters simply wanted to press the king to do more to alleviate food shortages. Others had the idea to force the royal household to relocate to Paris: Louis himself remained relatively popular, and these people wanted to move him away from scheming aristocrats. Still others may have had more murderous motives. The king’s wife, Marie Antoinette, was particularly unpopular, with many suspecting she had only foreign interests at heart, hailing as she did from longtime French rival Austria.

The atmosphere must have been highly charged, with at least 6000 people gathering here (some sources place the number closer to 10000).

Hôtel de Ville

The plaza in front of Paris’s city hall, then called the Place de Grève1, already had a centuries-long history as a location for protesters to gather. Indeed, the French word “grève”, meaning strike, takes its name from this square. The location has been the site of the city’s central administration since 1357; the building which stood there in 1789 had been built between 1535 and 1628. From the outside, this building looked much the same as today’s Hôtel de Ville, but it’s radically different on the inside: it was burned down at the end of the Paris Commune of 1871, and rebuilt in 1882.

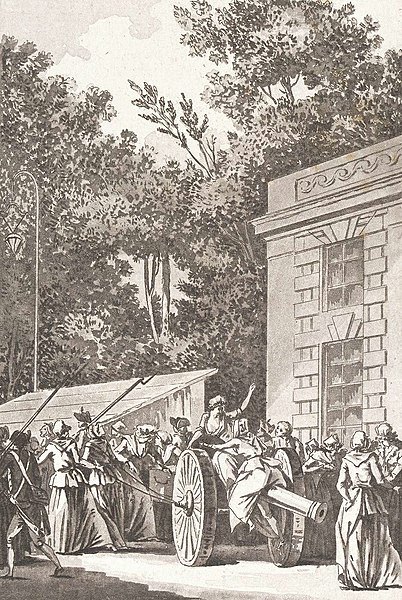

On the morning of 5 October 1789, the women gathering here raided the Hôtel de Ville itself, making off with weapons from the arsenal, including cannons which they would then transport to Versailles with their bare hands.

They headed off around ten o’clock. It was raining. For my part, I left at eleven under a grey sky; the forecast rain hadn’t arrived yet.

Voie Georges-Pompidou

The early part of the women’s route took them along the right bank of the Seine, so I started out along the Voie Georges-Pompidou, which was created in 1967 as an urban expressway before being pedestrianised in 2016.

Jardin des Tuileries

Once I reached the Passerelle Léopold-Sédar-Senghor, I turned to cross the Jardin des Tuileries. This garden was originally laid out to accompany the Palais des Tuileries, a royal palace built for Catherine de’ Medici in 1564 and serving as the main royal residence until the completion of the Château de Versailles in 1682 for Louis XIV. After the Women’s March, the Tuileries Palace would house Louis XVI and his family until the proclamation of a republic in 1792. Like the Hôtel de Ville, the palace was burned down during the Paris Commune, but unlike the city hall, this building was never rebuilt.

Place de la Concorde

The western end of the Tuileries garden opens onto the Place de la Concorde. This plaza, the largest in Paris, was opened in 1763 during the reign of Louis XV, and bore his name. When the Revolution of 1789 descended into the 1792 Reign of Terror, this square, renamed the Place de la Révolution, would be the site of many noteworthy executions, including those of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI. After the Directory rose to power in 1795, the square was renamed to today’s name as a sign of reconciliation after the bloody terror. After the Bourbon Restoration, it retook its original name, before briefly taking the name of the martyred Louis XVI; but it’s been officially known as the Place de la Concorde since the July Revolution of 1830.

Champs-Élysées

After crossing the Place Louis XV, the horde proceeded along the Avenue des Champs-Élysées. Probably Paris’s best-known street, this multilane road is often referred to in France as “la plus belle avenue du monde”. In my opinion it looks a lot more beautiful on the first Sunday of each month, when it’s pedestrianised.

The eastern section of the avenue, between the Place de la Concorde and the Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées, was first opened in 1667, flanked by formal gardens. It’s along this stretch that the women of 1789 marched, before turning south towards Versailles.

Avenue Montaigne

It’s unclear exactly which route the women took from here2, but I chose to turn at the Rond-Point and follow the Avenue Montaigne. At the time of the Revolution, this street was still undeveloped, lying as it did on the edge of town. But starting in the mid-19th century it became an exclusive address, lined with luxury mansions inhabited by bourgeois residents. Today, it’s the site of high-end fashion shops and five-star hotels.

Place de l’Alma

The Avenue Montaigne terminates in a major junction: the Place de l’Alma, at the northern end of the bridge of the same name. This square is probably most famous for the tunnel that passes under it, where Diana, Princess of Wales met her untimely death on 31 August 1997. The corner where the Flame of Liberty stands is officially known as the Place Diana.

The Avenue de New York and the Avenue du Président Kennedy

Here, the women continued along the river once more. The views along this stretch have changed considerably since 1789.

The first very conspicuous addition is the Eiffel Tower, erected on the Champ de Mars for the Exposition Universelle of 1889. A little further along on the left bank stand the high-rise buildings of the Front de Seine development, a controversial 1970s mixed-use estate.

None of the bridges which today cross the river here existed at the time: the next bridge after the Pont Royal was the Pont de Sèvres, some 10 km downstream. The Pont d’Iéna was completed in 1814 (its name references a Napoleonic victory). The first incarnation of the Pont de Grenelle was erected in 1827, while the Pont de Bir-Hakeim wasn’t completed until 1878. The Passerelle Debilly, a footbridge, and the Pont Rouelle, a railway bridge, were built for the 1900 Exposition Universelle. Even the Île aux Cygnes, a beautiful tree-lined walkway in the middle of the Seine, wasn’t created until 1825.

Looking away from the river, a few more landmarks stand out, including: the Palais de Tokyo and the Palais de Chaillot, both built for the Exposition Internationale of 1937; the Passy metro station, whose platforms are above ground at one end and underground at the other, and whose escalators can be used by passersby to help climb the steep hillside on which it stands; and the Maison de la Radio, a distinctive building opened in 1963 and serving as headquarters for Radio France.

At Passy, the women would have passed through a tax collection barrier, taking them outside the city walls.

The Avenue de Versailles and the Porte de Saint-Cloud

The name of the next street I followed reassured me that I was going the right way. Indeed, the Avenue de Versailles was once called the Route de Versailles, indicating its status as the main road to the seat of the kingdom’s government.

The Place de la Porte de Saint-Cloud, at the southwestern boundary of Paris, is a major roundabout, but it’s currently tamed by a protected coronapiste. Continuing over the boulevard périphérique, I definitively left Paris, entering the suburb3 of Boulogne-Billancourt.

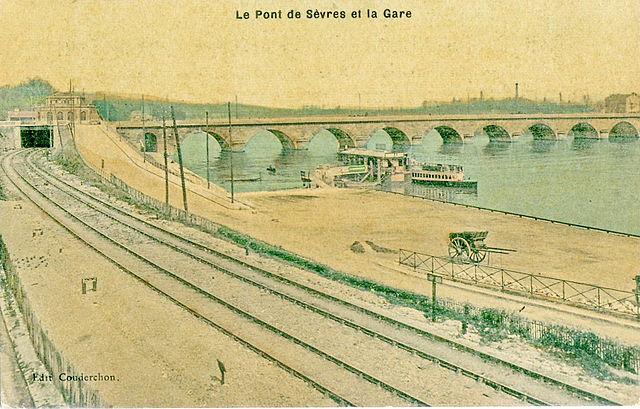

The Pont de Sèvres

The women of Paris crossed the Seine at the Pont de Sèvres, whose then incarnation was a little upstream of today’s bridge, passing over the downstream end of the Île Séguin.

Today, the Pont de Sèvres is a multimodal transport hub: on the right bank of the river (the side closest to Paris) lies the terminus of metro line 9 and a major bus station, while on the other side stands an old railway station, once of the line from Puteaux to Issy-Plaine, which closed to railway traffic in 1993. Since 1997, tram line T2 has stopped here, but the tramway does not use the railway station building. Plans are afoot to repurpose the building into a restaurant, a move that has been successful elsewhere in the region.

Sèvres

The town of Sèvres served as a rest stop for the crowd. However, when the women arrived here, they found everything closed: the inhabitants must have got wind of their imminent arrival. But the throng was able to negotiate with the locals for food and drink.

Versailles

As my walk neared its end, the rain began to fall in earnest; I passed through the towns of Chaville and Viroflay thinking of little other than putting one foot in front of the other. I imagine many of the Parisians must have felt similarly by this point as they neared the end of their six-hour trek.

Passing into the town of Versailles itself, I followed the Avenue de Paris, a grand tree-lined avenue leading to the palace gates. After stopping on the vast esplanade in front of the château for a moment of satisfaction at meeting my goal, I headed straight to the Gare de Versailles-Château-Rive-Gauche.

Finally seated on the warm, dry train that would carry me back to the city, I was very relieved that that was the end of my adventure. Yet for the Parisian women, this was only the first part of the story.

The story continues

As the women were arriving, at about 4 in the afternoon, thousands of National Guardsmen headed off from Paris to join them. Many of these men were keen to support the efforts of the crowd, and their Commander-in-Chief the Marquis de Lafayette, unable to stop them, decided instead to lead the way. They took a slightly different route, but arrived in Versailles around 10 pm.

The Parisians, though surely exhausted from the march, stood vigil overnight. At 5:30 am, someone managed to get into the inner courtyard, and the crowd made it all the way to the royal apartments. Marie-Antoinette in particular feared for her life, and it’s not hard to imagine a version of this story in which she meets a bloody end at this moment.

Prudently, Louis XVI took the advice of Lafayette to capitulate to the protesters’ demands for him to decamp to Paris. He appeared on the balcony promising this, and the crowd went wild. The National Guard having pledged allegiance to the king, the entire group of some 60000 people – royal court, Guard, Parisian masses, and the National Constituent Assembly – departed at 1 pm.

The king wouldn’t reach the Palais des Tuileries until 10 at night. But that was the end of his rule from Versailles, and another step along the road to the end of the monarchy. In 1792 he would be deposed from office, before meeting his demise at the guillotine in the Place de la Révolution.

-

The word “grève” meant a sandy or gravelly area by a body of water, as this riverside area had once been. ↩

-

All I could glean from the sources I consulted is that they started along the Champs-Élysées; if any reader knows better I would love to hear from you! ↩

-

I hesitated to use the word “suburb” here, as the commune of Boulogne-Billancourt is not really very different in character to the outer arrondissements of Paris. Much is often made of the divide between Paris proper and the surrounding towns, but, to an outsider at least, this divide isn’t noticeable. Boulogne certainly doesn’t feel “suburban” in character, at least not in the traditional British or American sense of the word. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris