Citizens across France went to the polls last Sunday for the first round of regional and departmental elections. Today they returned for round two. The regional government of Île-de-France has important powers when it comes to transport, so the result of the election could significantly impact the transport landscape over the next six years. So what does each candidate have to say on the subject?

Incumbent regional president Valérie Pécresse, supported by mainstream right-wing party Les Républicains, won this first round comfortably, and is highly likely to retain the presidency today. Her main rival is green Julien Bayou, who since coming in third place last week has allied with Audrey Pulvar of the socialists and Clémentine Autain of populist left party La France Insoumise. Also still in the race are Laurent Saint-Martin of Macron’s party LREM, and Jordan Bardella of the far-right Rassemblement National. Unfortunately, by far the biggest winner was abstention, with turnout at a record low of 30.85%.

With the opinion polls so clearly pointing to a victory for Pécresse, one might be forgiven for ignoring her opponents’ proposals. But I think this would be a mistake, as the candidates’ points of agreement and difference have a lot to tell us about the state – and the direction of travel – of one of Europe’s transport capitals. Drawing from the candidates’ manifestos1 and two televised election debates2 I’ve pulled together a summary of where today’s hopefuls stand on a number of key issues.

Commonalities

Security

It’s widely agreed that there is a problem of security on the transport network. Indeed, security more globally has been an important theme in this election campaign across the country, and looks set to play a major role in next year’s presidentials. However, the candidates diverge on what to do about it.

Pécresse has defended her record, boasting of 3000 new security cameras and of increasing the number of security staff from 2000 to 3000 since her election in 2015. Her administration also implemented a 24-hour hotline for those who experience or witness harassment or antisocial behaviour on the public transport system. Her opponents claim a phone line is powerless to stop aggressions as they occur, and that in any case it’s often difficult to get through. Autain claims the money spent on deploying cameras would be better invested in personnel, pointing out that CCTV is only as good as the people behind the scenes.

Saint-Martin has proposed a regional transport police, while Bayou has called for 1000 civilian agents on trains and night buses to prevent sexual harassment on board. The far-right Rassemblement National calls for two armed guards at the entrance to every RER station.

Cycling

Perhaps the most interesting development, compared to previous elections, is universal agreement that we need better cycling infrastructure. But again, there is significant divergence on the details.

Once again Pécresse can point to her record. At the proposal of cycling campaign groups she has rolled out the first stages of the RER Vélo, a 600 km network of secure bike lanes following the RER network. Her administration also created a programme offering up to €500 per person towards the purchase an electric bike, as well as Véligo Location, a regional scheme for long-term electric bike rental. But as Bayou has pointed out, Pécresse spent €130 000 of taxpayers’ money to mount a legal challenge to the pedestrianisation of the right bank of the Seine, which created a 3.3 km route for cyclists along the river.

Autain’s manifesto pledged to increase the share of trips in the region by bike from 2% to 12%. This would entail reinforcing the RER Vélo, rolling out a scheme similar to Véligo but with traditional bikes, and building new bike parking. But it’s unsurprisingly Bayou who was most ambitious on cycling, offering 1700 km of new cycle lanes, “100% cyclable” railway stations, and a free bicycle for every high school student. For her part, Pécresse introduced a €500 towards the purchase of a new electric bike. Far-right Bardella claims to support new cycling infrastructure, but paradoxically doesn’t want anything that inconveniences either motorists or pedestrians.

The 15-minute city

I wrote earlier this year about the concept of the 15-minute city, championed by Anne Hidalgo. Several candidates make suggestions which seem to echo this. Green Bayou is proposing good public transport within 15 minutes of every resident, with the help of on-demand transport in the region’s more rural areas. As part of his proposed “Green New Deal” (he uses the English term) he would place training centres for new green jobs within 30 minutes by public transport of every resident. And new healthcare centres would be accessible within 15 minutes.

Similarly, Saint-Martin promises a “10-15-30 region”: transport within 10 minutes of everyone (again, using on-demand services in more rural areas); commerce and public services within 15 minutes; and a high school within 30 minutes3. Pulvar’s manifesto promised transport within 15 minutes and 180 new health centres in currently underserved areas. For incumbent Pécresse, the magic number is 20: she wants to bring healthcare, schools, commerce, and sporting and cultural opportunities within 20 minutes of each resident. Like her rivals, she would expand on-demand transport, and turn each rural railway station into a “multiservice” building, bringing things like shops and crèches closer to homes.

Bayou, Autain and far-right Bardella have all promised to bring jobs closer to inhabitants: Autain deplores the existence of “dormitory towns”, while Bayou points out that 68% of the region’s jobs are concentrated in 6% of its territory. Macronist Saint-Martin takes a slightly different approach, talking instead of remote working hubs.

Using concepts like the 15-minute city to inspire better provision of public services is a very good thing. But realistically, the true 15-minute city depends on density. While some jobs can indeed be created in the hinterlands – providing new services will require hiring new people, and the greens want to invest in agriculture in the region’s rural areas – others can never realistically be delocalised to any great extent. Businesses choose to locate close to other businesses, in a process known as agglomeration. Many companies have begun to allow (and even encourage) remote working, but few want to go fully remote. Commuters will still be boarding the region’s trains for at least some of the week. And that’s without considering the many service jobs in Paris which cannot be delocalised. Retail is highly location-dependent, as is anything dependent on tourism.

Areas of division

Free public transport

In last year’s municipal elections, the LFI candidate proposed free public transport for all. I wrote about it, somewhat ridiculing the policy. But this year it was socialist candidate Pulvar – who serves in the administration of last year’s winner Hidalgo – who promised the measure. In fact, she made it the centrepiece of her campaign.

Pulvar claimed the policy would bring six main benefits: to save residents money; preserve health; act for the climate; make public transport a right that everyone can access; reduce congestion; and boost commerce and culture. She was promising to fund the measure with a tax on goods transit on the region’s roads, rather than with a tax hike for local residents, so let’s take her at her word on the first point. Provided it’s true, it could also have had some impact on commerce and culture. However, the claims about congestion, health and the climate are dubious: trials elsewhere have found that road traffic doesn’t durably decrease. Driving is already significantly more expensive than public transport, so people are mostly choosing to drive for one of two reasons: they cannot rely on transit for the journeys they take, or they prefer to spend the extra money for the perceived comfort of the automobile. Neither of these can be solved by reducing the price. To the extent that either can be remedied, it’s through spending money to improve the system. The goal of making transport accessible to all is a laudable one; but a more thorough understanding of the consequences wouldn’t hurt.

Autain, whose LFI comrade last year promised free transport for Parisians, was more circumspect, pledging it for under-25s and less well-off pensioners, but not for everyone. Other candidates were equally sceptical of Pulvar’s ability to raise the required funds, fearing that the measure would withhold funds vital for the numerous projects underway to improve the region’s transit. In the end, the united left under Bayou has ended up promising free transit only to under-18s, and young students and jobseekers. But now that the idea is on the table I suspect we’ll hear more voices on the left advocating full free transport in the coming years.

Grand Paris Express

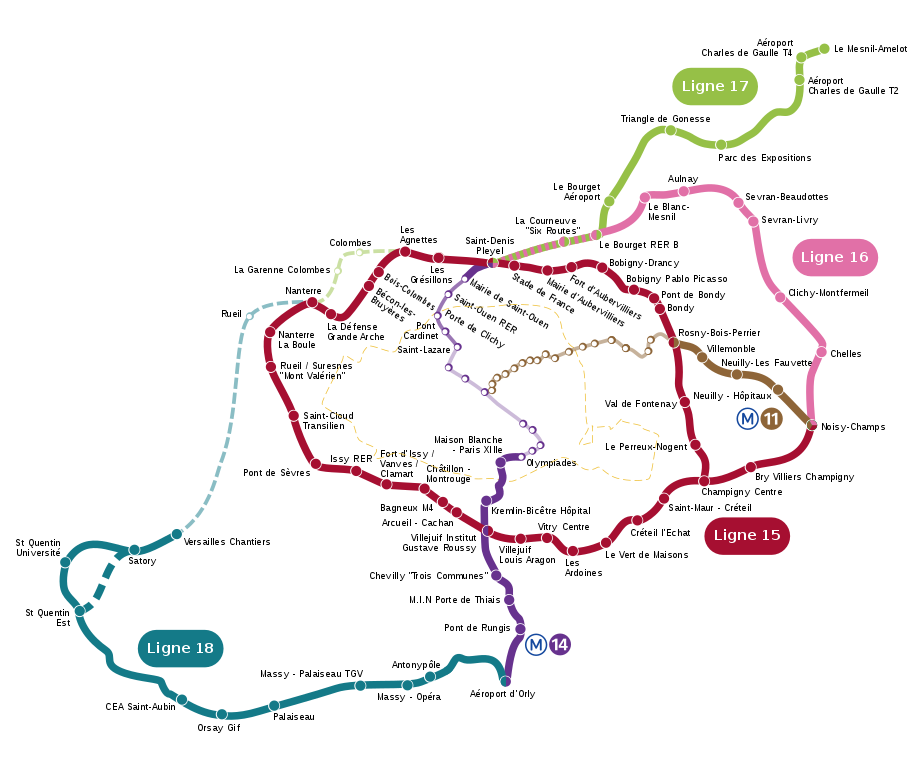

The major candidates agree on a number of measures to improve transport in the region: new tramways and BRT lines; better options in more rural areas, making use of on-demand services; and improvements to the RER, including new signalling on lines B and D. But the region’s – in fact the continent’s – largest urban transport project is more controversial. Work on the Grand Paris Express (GPE), the ambitious plan to double the length of the once exclusively Parisian metro network with four new lines in the suburbs, is already underway. But that doesn’t mean the project has unanimous support.

The far-right RN wants to cancel the GPE altogether and focus instead on improving other lines. The greens like lines 15 and 16, circumferential routes destined to improve journeys for millions of inhabitants of the inner suburbs, but baulk at lines 17 and 18. The success of line 17 depends largely on a proposed new terminal at Charles de Gaulle airport, which was cancelled in February this year, and the development of the Triangle de Gonesse, a greenfield site whose development EELV strongly opposes. They consider line 18 to be disproportionate relative to the needs of the area it serves, citing alternatives along the route such as tramways and cable cars. To be viable as a metro line, line 18 would require further greenfield developments. The plan includes a viaduct which they say would damage the local farmland.

Autain has also been highly critical of both the proposed Triangle de Gonesse station, and the most controversial section of line 18, west of Saclay. Pulvar’s manifesto didn’t touch the subject. The trio have been vague about the subject since allying this week, but the Triangle de Gonesse development looks dead on arrival if Bayou reaches the president’s office. For their part, incumbent Pécresse and national government-aligned Saint-Martin naturally defend the existing programme.

CDG Express

Currently the only rail link between Charles de Gaulle airport and central Paris is RER line B, which is at saturation. Long-distance travellers, luggage-laden and unused to the system, share crowded trains with local commuters. Some off-peak trains run non-stop between the Gare du Nord and the airport, which solves some problems but reduces the number of trains that can run.

A part of the answer, according to its proponents, is the CDG Express: a premium rail service offering direct non-stop journeys between the Gare de l’Est and the airport. They estimate that 35% of the new train’s ridership will come from the RER. Before the pandemic, ridership estimates were around 20 000 passengers per day, so new service would take 7000 passengers off the RER B. Again before the pandemic, the northern section of the RER line carried 395 000 passengers per day. So by the most optimistic estimates, the CDG Express would reduce footfall on that section by less than 2%. On the other hand, as the prefect4 pointed out in a 2019 interview, airport passengers with baggage take up a disproportionate amount of space.

With tickets priced at €24 each way, Bayou and Autain call it a train des riches and are pledging to cancel it. Bardella agrees. This framing will look uncomfortably familiar to anyone following the HS2 debate in England: the new high-speed train is panned as something that exists only to improve the lives of a few wealthy travellers, ignoring all the other potential benefits. But I think the high price point does explain why the predicted shift from the RER is relatively small. With taxis barely more expensive for parties of two – and often (depending on traffic) offering a more convenient service – it does seem to fill a relatively small niche. So I can understand the opposition.

On the other hand, opposing the CDG Express might just be a case of cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face. The region isn’t investing a cent in the line: most of the money is coming from a loan from the French State, expected to be covered by ticket sales. And the project will benefit other lines. Transilien K’s suburban trains will be able to reach higher speeds thanks to improvements to the track. And €492 million of the project’s €2.2 billion is dedicated to the RER B, which will see new sidings and a crucial step towards being able to carry double-decker trains5.

Privatisation

Valérie Pécresse is a vocal proponent of privatisation on the network. For buses in the outer suburbs it’s already happening, while the Transilien suburban rail network is next, starting in 2023. The new metro lines of the GPE will also be put to tender, much like the newest tram lines. The RATP tramways would be up for grabs from 2030, with the metro and RER following by 2040.

Clémentine Autain has cited Thatcher’s privatisation of public transport networks across the UK in voicing her opposition to this. British bus privatisation, which went further than virtually anywhere else in the world, is widely panned by public transport experts and users alike. Often, some areas are underserved while the most profitable routes see multiple competing companies, whose tickets cannot be shared. Andy Burnham, the Manchester mayor who has pledged to change things there, explains it succinctly in this video. But Autain’s reference to the failed British policy is a frankly dishonest mischaracterisation of what’s being pursued in Île-de-France.

In fact, privatisation here looks much more like the setup in London, which escaped the worst of Thatcher’s reforms. There – as here – operations are put to tender, but planning, ticketing and communications are the responsibility of a public body. Furthermore, nobody is proposing to sell off the SNCF or RATP. What’s happening is the introduction of a little competition, not the complete free-for-all seen in 1980s Britain.

Whatever the flaws in their rhetoric, the candidates of the left fear that the introduction of competition – particularly at the pace desired by Pécresse – might trigger a race to the bottom, with competition on price degrading service. The three are clear on their desire to stop the process.

Roundup

The incumbent looks to have this election in the bag. But regardless, it is interesting to see what the different candidates’ policies have in common. The cycling revolution is clearly underway, with politicians across the spectrum agreeing that we need new and better bike infrastructure. The concept of the 15-minute city, of which Paris is a global pioneer, is inspiring similar ideas, again across political lines.

As for the areas of disagreement, even these reveal commonalities. Some candidates are opposed to some transport initiatives, but they never argue against public transport in principle. All see buses, metros, trains and trams as an important part of the mix in one of the transport capitals of the world. Few want to make it free; but the very fact that a major candidate – from the party that held the presidency of the Republic five years ago and still controls the capital’s city hall – would run with this as her central policy is interesting. Whatever your view of the idea (I haven’t hidden my own scepticism) it does show that people value public transport. There’s a reason for optimism.

-

- The allied list of Autain, Bayou and Pulvar

- Clémentine Autain (LFI/PCF)

- Valérie Pécresse (Libres/LR)

- Audrey Pulvar (PS)

- Laurent Saint-Martin (LREM/MoDem)

-

- First round debate between Autain, Bayou, Pécresse, Pulvar, Saint-Martin and Wallerand de Saint-Just (representing Jordan Bardella)

- Second round debate between Bardella, Bayou, Pécresse and Saint-Martin

-

The region has responsibility for high schools; other schools are managed at the departmental and municipal level. ↩

-

The Prefect of Paris and Île-de-France represents the French State in the region. ↩

-

Currently line B, the second busiest line on the RER network, is the only one carrying only single-decker vehicles. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris