Last time, we looked at some of the big transport news from 2021, and what we can expect in 2022. But there’s one important subject I didn’t cover. The way we pay for our journeys is changing.

Pricing

Last summer, citizens across France went to the polls to elect regional and departmental councils. The Île-de-France region, which includes Paris and a wide area of surrounding suburbs, commuter towns and rural areas, has significant powers when it comes to transport. On the day of the election’s second round, I published a piece about the key areas of convergence and divergence on the subject between the main candidates for the region’s presidency.

One of the biggest headline grabbers was socialist candidate Audrey Pulvar’s proposal of making all public transport in the region completely free of charge. The journalist-turned-politician made it the centrepiece of her campaign; but she failed to cut through, rallying green Julien Bayou after a disappointing first round. I discussed my own scepticism of the proposition in the article.

In the event, incumbent Valérie Pécresse was comfortably reelected. But the right-winger had made her own promise about ticket pricing, enacted in September to take effect early this year. Single point-to-point rail journeys within the region, which can currently cost up to €15, will be capped at €5, or €4 when bought in a pack of 10. Regular transit users with Navigo passes will be unaffected, but the policy could make a big difference for occasional riders. I haven’t seen any indication that airport journeys are excluded, which means tourists might be among the first to notice the change. Today, a ticket to Paris from Charles-de-Gaulle airport by RER costs €10.30.

Moving on from paper

Another big change: the region is finally phasing out paper tickets, at least partially.

This began with the June 2019 launch of the Navigo Easy, a pay-as-you-go card which can hold T+ tickets (for metro, tram and bus services in the region and RER journeys within Paris) and several other types of ticket. The Navigo brand is already well-established, as seasonal passes already bear that name. But I have to say that, having lived in London and used the much more powerful Oyster card over a decade ago, I find the label “Easy” rather misleading. Tickets must be preloaded onto the card, and these don’t include rail journeys outside the city proper.

Following the rollout of the Navigo Easy, 10-packs of T+ tickets are now being phased out. In October 2021, around 100 metro stations stopped selling these; by the end of 2022, they will have disappeared completely. Passengers will still be able to buy the tickets individually, for a higher price. On buses, passengers can no longer buy tickets from drivers, but can use an SMS service if caught short aboard without a ticket.

Another initiative, which looks more promising than the Navigo Easy, was launched in November 2019. With the Navigo Liberté +, occasional riders who live in the region can take as many trips as they like, and are billed the following month. Unlike the paper T+ tickets and the digitised tickets on the Navigo Easy, the Liberté + allows for multimodal journeys between bus, tram, metro and RER. And it includes a daily price cap of €7.50. The change for 2022 is that this is being extended to rail journeys in the rest of the region. This has been promised for the end of the year, with the lower €4 cap applied to journeys using the card.

The Liberté + is a huge step forward, but remains a long way from the convenience of London’s Oyster card. What about the unbanked? What about tourists with foreign bank accounts, visiting for just a few days? The daily price cap is great, but why is there no weekly cap?

While we’re on the subject of things London does better than Paris: London’s 7-day and 1-month passes, which can start on any day of the week or month, make a lot more sense than Île-de-France’s weekly and monthly passes, which adhere to the Monday-Sunday week and the calendar month. And London’s daily cap applies until 4:30 the following morning, which strikes me as more logical than stopping at midnight.

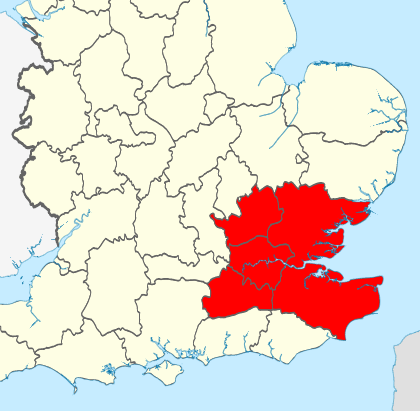

But I’d be remiss to sing London’s praises without mentioning the huge difference in the cost of travel. A monthly pass for the entire region – which covers an area the size of Greater London, Essex, Kent, Hertfordshire and Surrey combined – costs only €75.20. And that’s before you consider that French employers are obligated to foot the bill for half of their employees’ transport costs, on top of the transport taxes they already pay. While both cities’ transport networks have taken a big financial knock thanks to the pandemic, London’s is even more exposed than that of Île-de-France because of its greater reliance on the farebox. Both have had to seek bailouts from their nation’s central government – a politically fraught situation in both cases1 – but London might have to cut service to meet the shortfall. And as our friends at London Reconnections wrote in December, that’s unlikely to help in the long run.

Metro extension news

Finally: last time I discussed several metro extensions: the 14’s northern extension to Saint-Ouen and upcoming further extensions north to Saint-Denis and south to Orly; the 4’s recently opened southern extension to Bagneux; and the near-doubling in length of line 11, planned for 2023. But there’s another that I completely missed. Work began in 2007 to extend line 12 from Porte de la Chapelle into Aubervilliers, north of Paris. But while the tunnel was built all the way to Aubervilliers town hall, the stations were to be opened in phases. In 2012, Front Populaire opened, serving the southern end of the post-industrial business district of La Plaine Saint-Denis. In 2017, two more stations were set to open in Aubervilliers: Aimé Césaire and Mairie d’Aubervilliers. This was pushed back to 2019, and finally to spring 2022. It’s now expected this May.

For the sake of completeness, let’s have a look at some other proposed extensions to the metro network. A public enquiry is currently underway for three new stations on line 1, taking it east to Val de Fontenay. Here, it would join RER lines A and E, the new metro line 15, and the extended T1 tramway. This won’t see daylight until 2035. Several other extensions have been floated, but there are no official plans yet. Local newspaper Le Parisien produced a helpful infographic back in 2016 to illustrate these.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief look at changes to Paris’s transport system in the 2020s and beyond. Next time, we’ll jump back a century to continue our history of the tramways of Île-de-France.

-

The UK’s Conservative government is loath to help Labour-held London, while in Île-de-France the region’s president Valérie Pécresse is a candidate in April’s presidential election, and probably represents the most serious threat to Macron. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris