122 lines. 1100 km. 720 million passengers per year. These three numbers describe the tramway network of the Paris region at its peak.

In our history of the tramway so far, we’ve observed half a century of stops and starts, of experiments, successes and bankruptcies, of horses and steam power, compressed air and cables, conduits and studs and overhead wires. Now, as the first decade of the 20th century draws to a close, the chaotic web of different technologies and companies is starting, slowly, to consolidate. A couple of big shocks and the very visible hand of state intervention will accelerate this process as the network approaches its zenith.

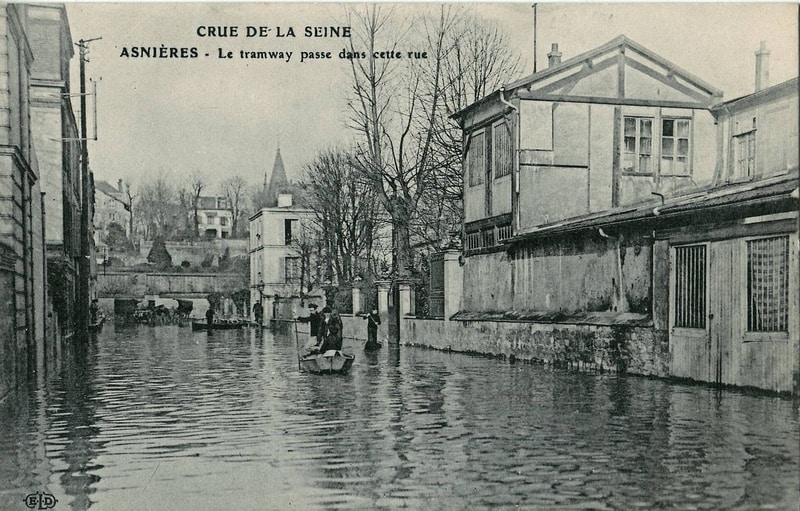

Flood

In January 1910, the Seine burst its banks in a flood of proportions not seen since. While no deaths were reported, the flood caused the equivalent of €1.6 billion of damage. Areas some distance from the river were submerged as water found its way through the sewers and newly dug metro tunnels. The tramway was among the flood’s most notable victims.

Barely a line was untouched: those that weren’t directly inundated were hit with shortages of electricity or rolling stock, as floodwaters put power stations and depots alike out of action. More directly, electric studs and conduits were short-circuited. Lines with overhead wires fared better, but their engines were still vulnerable. In many places, the rails themselves were damaged, bent out of shape by swollen wood.

By 1910, only three companies were still using the stud contact system. The flood destroyed most of what was left. Faced with an urgent situation, the city relaxed its rules, allowing overhead wires to replace the studs.

Remarkably, most of the network was back up and running by the end of February.

Reorganisation

With several major concessions up for renewal at the end of May 1910, the government decided to rationalise the network a little. As Paris and its suburbs densified, the tram network had grown along with it. But this growth had been haphazard and wasn’t serving passengers well.

Some of the existing companies were consolidated, bringing their number from 13 to 10. More significantly, a new line numbering scheme was introduced and pricing was simplified. And most importantly, the new concessions required electrification. Overhead wires were authorised throughout Paris’s outer neighbourhoods, with conduits remaining, for aesthetic reasons, in key places in the city centre. The last horsecars were withdrawn in 1912, with steam and compressed air following in 1914. Also in 1914, accumulator trams made their exit, along with the last remaining stud contact tramway. From then on, only Belleville’s unique cable tramway remained unelectrified, and every electric line was using either overhead wires or conduits.

War

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo. One month later, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. On 1 August, France mobilised for war. By the end of the year, trenches were dug across the country’s north east. They would remain for almost four years.

The tramway network had been modernising rapidly, especially since the reforms of 1910. Thanks to the war, this progress stalled. Both raw materials and production and maintenance capacity were diverted to the manufacture of weapons and aircraft parts. But the trams kept running. With so many men called away to fight, the tramways began to employ women drivers.

By 1918, the tram companies were in a dire situation. Maintenance had lagged for four years and costs were high and rising. The government refused to countenance raising fares, recognising the importance of affordable public transport. As early as July, the council of the Seine department (which covered Paris and its inner suburbs) decided to take matters into their own hands.

Unification

With the armistice signed in November 1918, it was time for Paris to get back on its feet (or should that be wheels?). In September 1920, the department signed deals to buy out the six largest tram companies. From 1 January 1921, most of Paris’s trams and buses were operated by the STCRP, or Société des transports en commun de la région parisienne (“Paris region public transport company”). Over the next four years, the newly formed public company would take over the remaining operators. For its part, the Belleville funicular was shut down in 1924, replaced by an STCRP bus.

The STCRP had a tricky task on its hands. After years of neglect, a staggering 60% of its tramway engines were unusable. The remainder were a hotchpotch of literally dozens of often incompatible models. And the network itself required a degree of rationalisation now that every line would be operated by the same company.

Modernisation

Rolling stock

The process of improving the rolling stock involved three key tasks. The first was selling off some of the least compatible vehicles. The STCRP made quick work of this in 1921 and 1922. Next, what was kept was renovated. Often this meant completely replacing the engines. In every case, the trams were repainted in green and cream, with a coloured badge to indicate the line number. Finally, the company needed new vehicles.

The STCRP employed its predecessor’s facilities for the work of renewing its vehicles. One site, Championnet in the 18th arrondissement, was selected for the production of new trams and buses. First opened in 1882 by the CGO (the principal operator within the city walls), today it’s the RATP’s central bus workshop, responsible for fixing and refitting buses, producing new parts, and selling old vehicles.

New trams were produced in two series: 100 in 1922 and 475 in 1923. Increasingly – with passenger numbers continuing to rise – trams consisted of two or even three cars. But these would be the last new vehicles on the Parisian tramway network until the 1990s.

Routes

A few tram lines were pruned or altered, where two competitors had run similar routes. On the other hand, several lines were created, and several others extended, to connect disjointed networks. For example, the CGO’s lines often terminated at the boundaries of Paris: some of these were extended to connect with suburban networks. A rational numbering scheme was also devised.

Overall, however, the STCRP made relatively few changes to the network. Expected to balance their books, they had to be prudent with new expenditures.

Future

In 1921, the tramways welcomed a little over 600 million passengers per year. By 1928, this had risen to 720 million. For the sake of comparison, the combined ridership of all bus services in Île-de-France in 2019 was around 1.4 billion.

In the face of this growth, the STCRP published a 1925 plan envisaging a major expansion of both tram and bus coverage. In particular, they proposed a number of new lines between the suburbs, reducing the need for passengers to change in the city. Many of these would be express lines intended for long distances. Dozens of other measures were proposed, including new rolling stock, reserved rights of way, and a new ring of tramways to link the city’s main rail termini.

Very little of the plan went ahead. Of all the new lines proposed in 1925, only one was built, and it survived just two years. The failure to develop the tramway into a modern network was partly a problem of funds. But as we shall see next time, it was also an issue of priorities. Within a few short years, trams would have disappeared from the capital.

Given the modernisation efforts of the 1920s, and with footfall growing throughout the decade, it seems absurd that by 1938, not a single tram would be running in the region, save for a distinct network all the way out in Versailles. Next time, we’ll trace the story of the tramway’s demise. Be sure to sign up for email updates below so you don’t miss the next instalment.

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris