Few roads anywhere are as culturally significant as Paris’s boulevard périphérique, known affectionately as the “périph”. Used daily by hundreds of thousands of people, this inner ring road fills many drivers with fear. But beyond its status as one of Europe’s busiest roads, the boulevard acts as a symbolic wall. On one side: Paris. On the other: the rest of the world.

This fully grade-separated, controlled-access highway lies only about 5 km from the centre of one of Europe’s most populous metropolises. 100 000 people live within 100 metres of this road, which serves 1.5 million trips every weekday on its eight lanes. In particular, dozens of social housing blocks, schools and sporting facilities lie within nose- and earshot of this major source of air and noise pollution. How did this happen? Who uses the périph, and why? And what does the future hold for France’s best-known road?

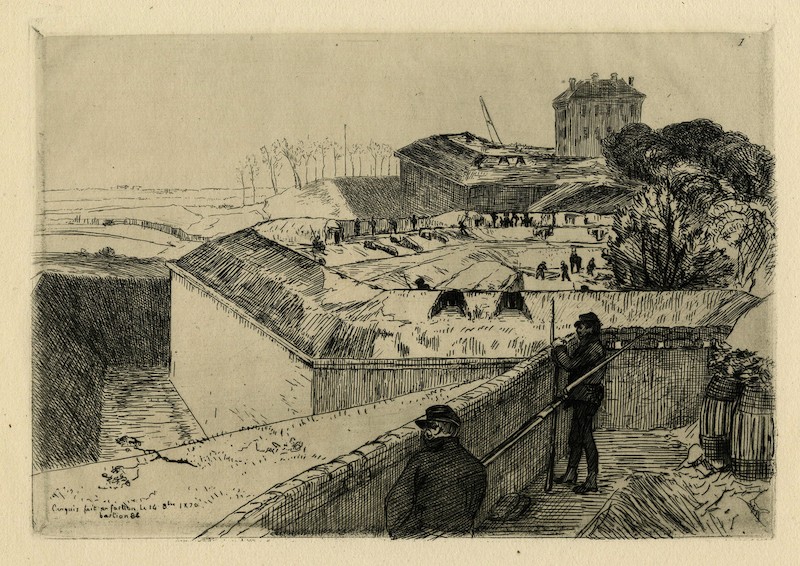

The Thiers wall

The story of the périph began in the 1840s, with the construction of the Thiers wall. Paris’s previous defensive wall had been demolished in the 17th century, when France was confident enough in its external borders to consider walling its capital unnecessary. Well-placed as that confidence might have been during the reign of Louis XIV, times had changed by the era of Napoleon. In 1814, the Sixth Coalition took the city after a single day of fighting. Within a week, the emperor had abdicated.

The question resurfaced during the reign of Louis Philippe, who took the throne after the July Revolution of 1830. With the threat of war never very far away, particularly in the context of the European powers’ clashing colonial ambitions, it was thought wise to protect the French capital with not only a wall, but a series of forts outside the city. Despite opposition from the parliamentary left – who feared that the wall was more about controlling any potential uprisings than defending the people – the defences were voted through in 1841, and construction completed in 1844. The wall is named for Adolphe Thiers, who proposed it during his brief tenure as prime minister in 1840.

Originally built in the suburbs some distance from the city proper, the wall became the official boundary of Paris in the annexation of 1860. On the outside of the wall sat a 40-metre-wide ditch, followed by a glacis 250 metres in width.

The Thiers defences received a major test in September 1870, when Prussian forces laid siege to Paris. The city held out until January, but the siege’s effect on the city was brutal and the French authorities knew they couldn’t survive much longer. With French troops faring badly elsewhere, and with German artillery eventually managing to break through Paris’s defences, France negotiated a humiliating armistice.

After the Franco-Prussian War came a brief civil war, which pitted a right-leaning government, based in Versailles and led by none other than 73-year-old Adolphe Thiers, against the revolutionary Paris Commune. In May 1871, Thiers’s forces began bombarding the Thiers wall. Soon afterwards, the Commune had fallen.

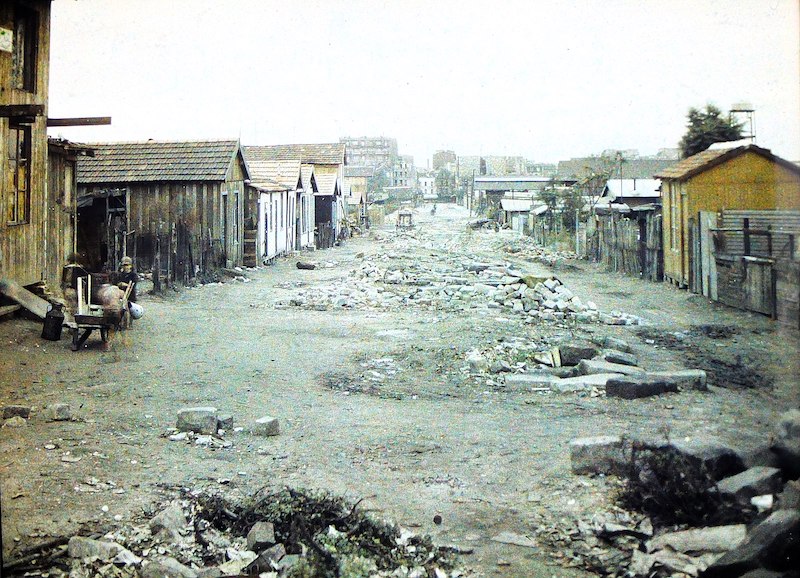

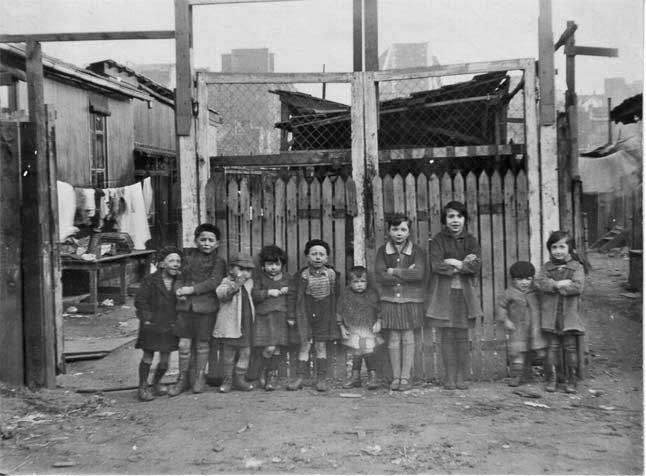

The Zone

The wall was already obsolete. Prussian successes in the war demonstrated that modern artillery was capable of overcoming such a barrier. It would subsist for another several decades, but its time as a defensive structure was over. The 250-metre-wide glacis remained out of the reach of developers, with construction banned throughout the zone. But as it was no longer serving any military purpose, it was soon occupied by migrant workers, travellers and others with nowhere else to go. The wall was finally dismantled after the end of the First World War, by which time this vast slum – known simply as La Zone – counted some 42000 residents.

The wall stood useless for nearly half a century before the demolition work began. It wouldn’t be fully dismantled until 1929. But long before the defences were officially decommissioned, the Zone was the subject of ambitious regeneration proposals. Adolphe Alphand, famous for the creation of dozens of parks during Baron Haussmann’s renovations of Paris in the mid-19th century, imagined a belt of greenery and relaxation, featuring parks, hotels and casinos. Later, others proposed modern housing developments, again surrounded by green spaces. In the end, the area occupied by the wall itself was given over to social housing. But the Zone beyond remained as it was into the second half of the 20th century.

The road

As we discussed in the story of the decline and fall of Paris’s tram network in the 1930s, the motorcar was taking hold as a symbol of freedom and of the future. As the French economy recovered from the Second World War and the car became affordable to more and more people, its reputation as the transport of choice gained strength.

By the 1940s, the boulevards des Maréchaux – the city streets which had once functioned as the inner access road to the Thiers defences – were already becoming saturated with car traffic. Alongside proposals to build new schools, parks and sports grounds in the Zone, there arose the idea of a “boulevard périphérique”. At first, this was imagined as just another urban street – a genuine “boulevard” in the model of those of Louis XIV.

Naturally, it was assumed that the best way to relieve congestion was to devote more space to cars. This was a rather more forgivable assumption in the 1940s than it is today, when cities around the world continue to construct new highways, ignoring decades of evidence of induced demand. By 1954, the plans had taken on a new shape. The boulevard would be a multilane, grade-separated, controlled-access road. It seems no one considered that installing what would become the busiest road in the country alongside sporting facilities for school children might not be the best move for public health.

The first section of the new ring road was inaugurated in 1960, but it wasn’t completed until 1973 – just months before a global oil crisis which signalled the end of the post-war boom, and with it the beginning of the end of car supremacy. Had it not been for that crisis, Paris might have been carved up by motorways; as late as 1971, president Georges Pompidou had said that Paris should be “adapted” to the automobile.

The situation today

Predictably, the périph was already jammed from the outset. But after peaking in the 1990s, the level of traffic has actually fallen by around a quarter. So has the speed limit, which was brought down from 90 to 80 in 1993, then to 70 in 2014. Yet it remains a very heavily used road, which generates significant noise and air pollution. It has also served to perpetuate the barrier between Paris and its surroundings.

The use of roads to divide communities is well-documented in the United States. Starting in the 1950s, dozens of majority-Black neighbourhoods saw buildings ripped down to make room for interstate highways. The damage went beyond the short-term destruction: many of these communities never recovered, as areas once closely connected were partitioned by the roads. Journeys that could previously be accomplished with a five-minute walk now required a long drive. In Paris, a 1960s motorway plan would have divided working-class districts in the east; the highways built in the city’s more affluent west would have been tunnelled. Fortunately, that plan never came to fruition; but with the construction of the périphérique, those social housing developments built at the site of the Thiers wall now found themselves sandwiched between a highway and the busy, multilane boulevards des Maréchaux. In places, particularly the north east, rail infrastructure further hems communities in.

In addition to 29 sports grounds and as many as 100 schools and nurseries, the périph is surrounded on both sides by housing and office buildings. The area is also constantly welcoming new developments. Central Paris is already very densely built, and quite understandable laws control the heights of buildings there. Meanwhile, the Zone’s peculiar history and the industrial history of much of Paris’s outer edge means that most of the city’s new construction happens within a few hundred metres of the highway. Given the intensity of the housing shortage in Paris, it’s hard to argue that much of this development isn’t necessary. But should we continue to build homes in areas so directly impacted by one of Europe’s noisiest, fumiest roads?

The future

There are two ways to attack that question. One would be to stop building near the boulevard. But it’s the other the municipality is pursuing: changing the road itself.

Speed

The périph is currently subject to a 70 km/h speed limit. As of 2021, the municipal government was considering reducing this to 50. According to Bruitparif, a nonprofit measuring and combating noise in Paris, this could reduce the road’s noise output by 2 to 3 dB. However, in spring 2022, mayor Hidalgo said this measure – which is unsurprisingly unpopular with regular périph users – isn’t the priority for now. She hinted it might come later.

Reserved lanes

During the 2024 Olympics, an Olympic lane will be introduced on the périphérique. For three quarters of the road’s length, one lane will be reserved for Olympic traffic: competitors, journalists, and so forth. Naturally, emergency vehicles will also be allowed to use the lane. The remaining quarter, in the south, is not only further from the Olympic Village, but a large part of it counts only three lanes in each direction, compared with four or more elsewhere.

The Olympic lane will require cameras to enforce it. The municipal government hopes to keep that infrastructure in place after the Games to create a lane reserved for high-occupancy vehicles. A relative novelty on this side of the Atlantic, it’s not without its detractors.

Redesigned junctions

The périphérique’s exits are known as portes – “gates” – taking their name from the gates of the former wall. This is perhaps fitting, as the road serves as a significant barrier in its own right. Many of today’s portes are dangerous traffic intersections, making it difficult for pedestrians on either side to get across, and reinforcing the sense of separation between the city and its periphery. But what if they could really serve as points of passage between adjacent neighbourhoods?

According to the city’s plans, 22 of the périph’s 39 portes will be transformed by 2030. The general approach consists of burying the highway, reducing the space given to cars in the intersection above, and creating a public plaza with the liberated land.

Much of this work has already been underway for years. In 2007, after two years of construction, the road was tunnelled at the Porte des Lilas. A bus station opened there in 2009; a park (named after Serge Gainsbourg1) was added in 2011; and in recent years it’s been the site of a number of building developments. Three other portes have already been transformed, with five more due by 2024.

On the list for 2030 is the Porte de Bercy. Today, this is one of the périphérique’s busiest and most complex interchanges. On the inside, it connects to the Voie Georges-Pompidou and the boulevards des Maréchaux; on the outside, it joins the A4 motorway and provides local access to the suburb of Charenton-le-Pont, and in particular the Bercy 2 shopping centre. The area is bounded on the north by a wide area of railway lines leading to Bercy and the Gare de Lyon, on the west by an industrial wasteland around the disused Petite Ceinture railway, and on the south by the A4. The plan is to create a new link between the 12th arrondissement of Paris and the town of Charenton, building homes for 3800 people and 6000 m² of offices and creating a 3.5 hectare park. An old station of the Petite Ceinture, currently empty, will be reappropriated, while Bercy 2 will be converted to a new use. The Renzo Piano-designed mall, opened in 1990, was previously touted for demolition.

An urban boulevard

As it stands, the plan for 2030 involves reducing the number of lanes to three, one of which will be reserved for high-occupancy vehicles (including buses), and building thousands of trees alongside the road, including in the space created by reducing the width. But city officials have said they want the transformation to go a lot further. Mayor Hidalgo’s 2020 manifesto envisaged traffic lights and even pedestrian crossings on the road. The idea is to transform the périphérique from what you might call a “boulevard with motorway characteristics” to a genuine urban boulevard, with at-grade junctions and access for people on bikes and on foot.

When the manifesto was published, the proposal met widespread disdain. This was in large part thanks to misleading headlines, and perhaps a failure to properly explain the timescale. But there are good reasons to question the idea.

Challenges

Redesigning the périph is not without its challenges. As it wasn’t built as an urban boulevard, only 10% of it is at-grade. Even here, wherever it crosses other roads it does so by way of one of 253 bridges. It’s not much use running buses along a road that’s either five metres above where people want to be, or at the bottom of a trench – or worse, a tunnel. And it’s even less appealing for people on bikes.

A true boulevard is a destination, with businesses along its sides. If the city finds a way to make that happen – a massive undertaking involving levelling viaducts and filling in trenches for most of the road’s 35 km length – then its job still won’t be finished. Arguably worse than a segregated urban highway is a non-segregated one, like the rue de Rivoli of yesteryear, the present-day Champs-Élysées, or London’s deadly North Circular. To create a truly pleasant space for people walking or on bikes, there must be strict limits on noise and air pollution.

It seems to me that the best long-term solution for the périph would be its total destruction. But given the financial and political costs of such a move, I think the best we can hope for – at least in the foreseeable future – is a “lite” version of what we have now, with less traffic and a reduced speed limit. Still, if it is opened to pedestrians, I will be among the first to take advantage of the chance to cross one of the city’s most interesting bridges on foot.

-

Gainsbourg’s 1958 single Le Poinçonneur des Lilas describes a metro ticket inspector from the neighbouring town of Les Lilas. Gainsbourg, who died in 1991, will also give his name to a new metro station when line 11 is extended through the town in 2023. ↩

Fabric of Paris

Fabric of Paris